Editorials

‘Cherry Falls’ Dares to Defy the Classic Anti-Sex Message of Slashers [Young Blood]

The Richmond-adjacent parts of Virginia that director Geoffrey Wright shot Cherry Falls in were not too welcoming once they became aware of the film’s plot. The residents were beside themselves after hearing the story’s killer was preying on teen virgins. According to Fangoria #196, a local op-ed lambasted the film before its release, going as far as to say it had “no heart, no originality, no conscience, and no soul.”

Considering the historical relationship between sex and death in all the slashers that came before Cherry Falls though, would the detractors have felt more comfortable if the film’s villain only slaughtered the sexually active? Slicing up the chaste was somehow out of the question, but perhaps a conventional slasher would have been more to their liking.

Cherry Falls is more complicated than its elevator pitch, although it admittedly starts off like other slashers before hurtling toward unknown territory. In the film’s suburban namesake, a fictional small town in Virginia, teenage Rod and Stacy (Jesse Bradford, Bre Blair) are necking in the woods one night when a car suddenly pulls up behind them. The driver, a woman in black whose face is obscured by her hair the entire time, then offs the lovers. Elsewhere on the same night, Jody Marken (Brittany Murphy) rebuffs the sexual advances of her boyfriend, Kenny Ascott (Gabriel Mann). These two scenes have similar setups; they show young couples in the throes of passion before the girlfriends slam on the brakes. Aside from the obvious murder aspect, the most glaring difference between these intimate displays is the outcome. Rod is understanding with Stacy, whereas Kenny breaks up with Jody on the spot.

A notable takeaway from classic slashers is sex leads to death. Be it frisky campers interrupted by a killer, or parked teens caught off guard by a violent peeper, the subgenre has a long tradition of punishing sexuality and rewarding abstinence. Celibacy offering an ounce of karmic protection against murderers and monsters was more or less implied until Scream made everyone fully conscious of the plot fixture. Cherry Falls writer Ken Selden, on the other hand, sidesteps the self-awareness innate to turn-of-the-millennium horror. He and Wright deconstruct slashers’ sexual politics without scoffing too loudly in the same breath.

Teen films by and large are fixated on sex because it is an exceedingly relatable topic for both storytellers and audiences. Other adolescent stories have their characters feeling mortified if they graduate high school with their virginities intact, but Cherry Falls’ characters chase carnal pleasure because their lives are at stake. They seek agency in a dire situation. The typical social repercussion of not doing the deed is accounted for; two couples break up with disparate levels of fuss involved. The film then presents an unprecedented consequence of chastity after a third murder establishes a pattern.

From Halloween to Friday the 13th, there is an unmistakable death sentence attached to sex scenes in horror. The antagonist has a bizarre habit of appearing during or after coitus. Of course the characters have no inkling of what fornication incurs, but like many American high schools, horrors of yesteryear routinely promote abstinence by showing the unduly negative effects of having sex. Then comes along Cherry Falls, a neo-slasher that turns the whole idea on its head. In any other film, a man like Jody’s father, Sheriff Marken (Michael Biehn), would be outraged at the thought of his daughter going past first base, but here he is disappointed when he learns his little girl is still on the assailant’s radar. Jody always seeks her father’s approval and thinks staying “pure” is the best way to get it. Imagine her surprise when she essentially now has permission to go all the way.

In the past, the “final girl” character was inexperienced with most things. If there was any sex to be had in her film, it was usually among her friends. Jody, who is by default not like other predestined slasher survivors thanks to her black-on-black attire and Murphy’s raw performance, breaks the mold even further once word gets around about the killer’s hankering for virgins. In a role reversal, she is now less inhibited, as evident by her reunion with Kenny. Jody pounces on Kenny after a round of footsie foreplay, but he stops her for a change; he suspects Jody is only with him again for practical reasons.

The boyfriend can either be pushy or respectful about sex; there is no set standard in horror. Meanwhile, Kenny is seen as a jerk when he first breaks up with Jody. The truth of the matter is that Kenny deeply associates sex with love, and since they never did much more than kissing after dating for a year, he assumed Jody did not return his feelings. So while Cherry Falls is neither the first nor last slasher to switch things up in the boyfriend-girlfriend department, it stands out when looking at how films from this era of horror revised long-standing gender roles and expectations.

When the student body learns of the killer’s M.O., they organize a massive orgy inside an old house. Throwing a party in these deadly times always spells doom for those involved, but the young folks here are coming together as a means of protecting themselves. What was once a death penalty in slashers is now the best chance for survival.

As risqué as a modern bacchanalia for teens sounds though, the event itself is not remotely racy. There is no collective copulation beneath a “sea of white sheets,” and there is certainly no full-frontal nudity either. Selden did not set out to make an especially gory film, but his biggest set piece was in fact castrated by the MPAA. The horror genre specifically felt the heat following the Columbine High School shooting. A major rewrite was required to avoid being hit with an X rating. As a result, the buildup toward an unbridled sex-for-all is for all for nothing, seeing as the orgy turns into a glorified sleepover with more heavy petty than actual sex. However, in the final cut’s defense, this flaccid version is fitting for a bunch of horny yet awkward teenagers who only talk a big game.

Without revealing the killer’s identity, Cherry Falls sharply falls on familiar ground by connecting the past to the present. The villain’s motive is fueled by generational trauma. Slashers have been dismissed as puerile and lightweight, yet looking back through the whole subgenre, there are stories that emphasize the antagonist’s harrowing origin. The killer struggles to make sense of their own unbearable pathos as best they can in these films, and they then cope with their emotional injuries by inflicting physical pain onto others. Simply put, hurt people hurt people. Cherry Falls’s biggest shock stems from the reveal of not the killer’s identity but how they reached this point of no return, and who among the main cast has everything to do with their tragic upbringing.

The struggle between prudery and creativity continues two decades after Cherry Falls was first released in a post-Columbine world. Sexless filmmaking is on the go these days, but like slashers, sex is bound to make a comeback in cinema sooner or later. It remains unclear if fans will see an uncut version of Cherry Falls anytime soon. In its only available form though, Wright and Selden’s collaboration is still a solid jumping-off point for discourse on sexual intercourse in horror. The film is audacious and thought provoking even in its sterilized state.

Horror contemplates in great detail how young people handle inordinate situations and all of life’s unexpected challenges. While the genre forces characters of every age to face their fears, it is especially interested in how youths might fare in life-or-death scenarios.

The column Young Blood is dedicated to horror stories for and about teenagers, as well as other young folks on the brink of terror.

Editorials

Five Serial Killer Horror Movies to Watch Before ‘Longlegs’

Here’s what we know about Longlegs so far. It’s coming in July of 2024, it’s directed by Osgood Perkins (The Blackcoat’s Daughter), and it features Maika Monroe (It Follows) as an FBI agent who discovers a personal connection between her and a serial killer who has ties to the occult. We know that the serial killer is going to be played by none other than Nicolas Cage and that the marketing has been nothing short of cryptic excellence up to this point.

At the very least, we can assume NEON’s upcoming film is going to be a dark, horror-fueled hunt for a serial killer. With that in mind, let’s take a look at five disturbing serial killers-versus-law-enforcement stories to get us even more jacked up for Longlegs.

MEMORIES OF MURDER (2003)

This South Korean film directed by Oscar-winning director Bong Joon-ho (Parasite) is a wild ride. The film features a handful of cops who seem like total goofs investigating a serial killer who brutally murders women who are out and wearing red on rainy evenings. The cops are tired, unorganized, and border on stoner comedy levels of idiocy. The movie at first seems to have a strange level of forgiveness for these characters as they try to pin the murders on a mentally handicapped person at one point, beating him and trying to coerce him into a confession for crimes he didn’t commit. A serious cop from the big city comes down to help with the case and is able to instill order.

But still, the killer evades and provokes not only the police but an entire country as everyone becomes more unstable and paranoid with each grizzly murder and sex crime.

I’ve never seen a film with a stranger tone than Memories of Murder. A movie that deals with such serious issues but has such fallible, seemingly nonserious people at its core. As the film rolls on and more women are murdered, you realize that a lot of these faults come from men who are hopeless and desperate to catch a killer in a country that – much like in another great serial killer story, Citizen X – is doing more harm to their plight than good.

Major spoiler warning: What makes Memories of Murder somehow more haunting is that it’s loosely based on a true story. It is a story where the real-life killer hadn’t been caught at the time of the film’s release. It ends with our main character Detective Park (Song Kang-ho), now a salesman, looking hopelessly at the audience (or judgingly) as the credits roll. Over sixteen years later the killer, Lee Choon Jae, was found using DNA evidence. He was already serving a life sentence for another murder. Choon Jae even admitted to watching the film during his court case saying, “I just watched it as a movie, I had no feeling or emotion towards the movie.”

In the end, Memories of Murder is a must-see for fans of the subgenre. The film juggles an almost slapstick tone with that of a dark murder mystery and yet, in the end, works like a charm.

CURE (1997)

If you watched 2023’s Hypnotic and thought to yourself, “A killer who hypnotizes his victims to get them to do his bidding is a pretty cool idea. I only wish it were a better movie!” Boy, do I have great news for you.

In Cure (spoilers ahead), a detective (Koji Yakusho) and forensic psychologist (Tsuyoshi Ujiki) team up to find a serial killer who’s brutally marking their victims by cutting a large “X” into their throats and chests. Not just a little “X” mind you but a big, gross, flappy one.

At each crime scene, the murderer is there and is coherent and willing to cooperate. They can remember committing the crimes but can’t remember why. Each of these murders is creepy on a cellular level because we watch the killers act out these crimes with zero emotion. They feel different than your average movie murder. Colder….meaner.

What’s going on here is that a man named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) is walking around and somehow manipulating people’s minds using the flame of a lighter and a strange conversational cadence to hypnotize them and convince them to murder. The detectives eventually catch him but are unable to understand the scope of what’s happening before it’s too late.

If you thought dealing with a psychopathic murderer was hard, imagine dealing with one who could convince you to go home and murder your wife. Not only is Cure amazingly filmed and edited but it has more horror elements than your average serial killer film.

MANHUNTER (1986)

In the first-ever Hannibal Lecter story brought in front of the cameras, Detective Will Graham (William Petersen) finds his serial killers by stepping into their headspace. This is how he caught Hannibal Lecter (played here by Brian Cox), but not without paying a price. Graham became so obsessed with his cases that he ended up having a mental breakdown.

In Manhunter, Graham not only has to deal with Lecter playing psychological games with him from behind bars but a new serial killer in Francis Dolarhyde (in a legendary performance by Tom Noonan). One who likes to wear pantyhose on his head and murder entire families so that he can feel “seen” and “accepted” in their dead eyes. At one point Lecter even finds a way to gift Graham’s home address to the new killer via personal ads in a newspaper.

Michael Mann (Heat, Thief) directed a film that was far too stylish for its time but that fans and critics both would have loved today in the same way we appreciate movies like Nightcrawler or Drive. From the soundtrack to the visuals to the in-depth psychoanalysis of an insanely disturbed protagonist and the man trying to catch him. We watch Graham completely lose his shit and unravel as he takes us through the psyche of our killer. Which is as fascinating as it is fucked.

Manhunter is a classic case of a serial killer-versus-detective story where each side of the coin is tarnished in their own way when it’s all said and done. As Detective Park put it in Memories of Murder, “What kind of detective sleeps at night?”

INSOMNIA (2002)

Maybe it’s because of the foggy atmosphere. Maybe it’s because it’s the only film in Christopher Nolan’s filmography he didn’t write as well as direct. But for some reason, Insomnia always feels forgotten about whenever we give Nolan his flowers for whatever his latest cinematic achievement is.

Whatever the case, I know it’s no fault of the quality of the film, because Insomnia is a certified serial killer classic that adds several unique layers to the detective/killer dynamic. One way to create an extreme sense of unease with a movie villain is to cast someone you’d never expect in the role, which is exactly what Nolan did by casting the hilarious and sweet Robin Williams as a manipulative child murderer. He capped that off by casting Al Pacino as the embattled detective hunting him down.

This dynamic was fascinating as Williams was creepy and clever in the role. He was subdued in a way that was never boring but believable. On the other side of it, Al Pacino felt as if he’d walked straight off the set of 1995’s Heat and onto this one. A broken and imperfect man trying to stop a far worse one.

Aside from the stellar acting, Insomnia stands out because of its unique setting and plot. Both working against the detective. The investigation is taking place in a part of Alaska where the sun never goes down. This creates a beautiful, nightmare atmosphere where by the end of it, Pacino’s character is like a Freddy Krueger victim in the leadup to their eventual, exhausted death as he runs around town trying to catch a serial killer while dealing with the debilitating effects of insomnia. Meanwhile, he’s under an internal affairs investigation for planting evidence to catch another child killer and accidentally shoots his partner who he just found out is about to testify against him. The kicker here is that the killer knows what happened that fateful day and is using it to blackmail Pacino’s character into letting him get away with his own crimes.

If this is the kind of “what would you do?” intrigue we get with the story from Longlegs? We’ll be in for a treat. Hoo-ah.

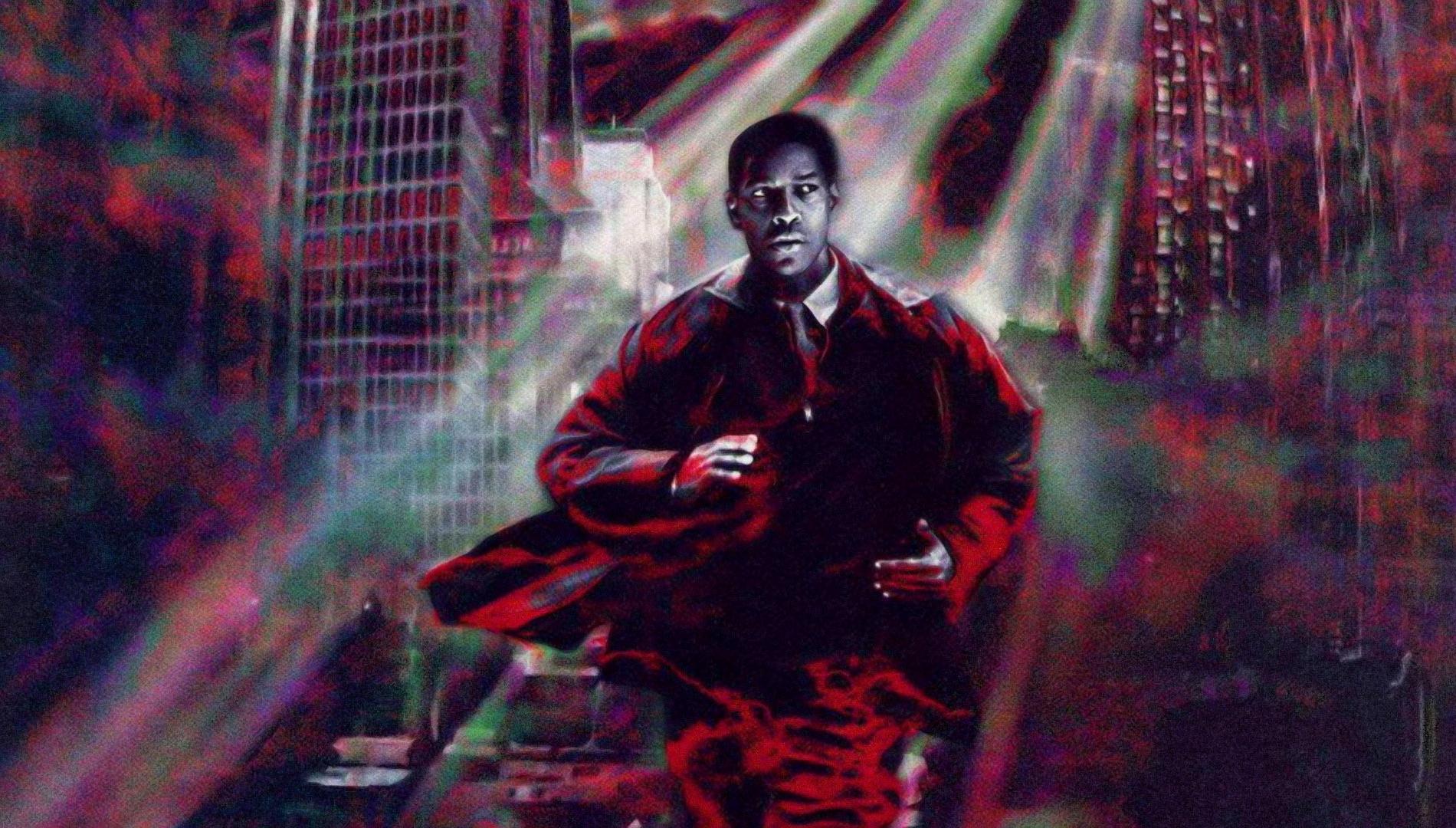

FALLEN (1998)

Fallen may not be nearly as obscure as Memories of Murder or Cure. Hell, it boasts an all-star cast of Denzel Washington, John Goodman, Donald Sutherland, James Gandolfini, and Elias Koteas. But when you bring it up around anyone who has seen it, their ears perk up, and the word “underrated” usually follows. And when it comes to the occult tie-ins that Longlegs will allegedly have? Fallen may be the most appropriate film on this entire list.

In the movie, Detective Hobbs (Washington) catches vicious serial killer Edgar Reese (Koteas) who seems to place some sort of curse on him during Hobbs’ victory lap. After Reese is put to death via electric chair, dead bodies start popping up all over town with his M.O., eventually pointing towards Hobbs as the culprit. After all, Reese is dead. As Hobbs investigates he realizes that a fallen angel named Azazel is possessing human body after human body and using them to commit occult murders. It has its eyes fixated on him, his co-workers, and family members; wrecking their lives or flat-out murdering them one by one until the whole world is damned.

Mixing a demonic entity into a detective/serial killer story is fascinating because it puts our detective in the unsettling position of being the one who is hunted. How the hell do you stop a demon who can inhabit anyone they want with a mere touch?!

Fallen is a great mix of detective story and supernatural horror tale. Not only are we treated to Denzel Washington as the lead in a grim noir (complete with narration) as he uncovers this occult storyline, but we’re left with a pretty great “what would you do?” situation in a movie that isn’t afraid to take the story to some dark places. Especially when it comes to the way the film ends. It’s a great horror thriller in the same vein as Frailty but with a little more detective work mixed in.

Look for Longlegs in theaters on July 12, 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.