Editorials

‘Tetsuo II: Body Hammer’ – Cyberpunk Body Horror Classic Spawned a Wild Sequel 30 Years Ago

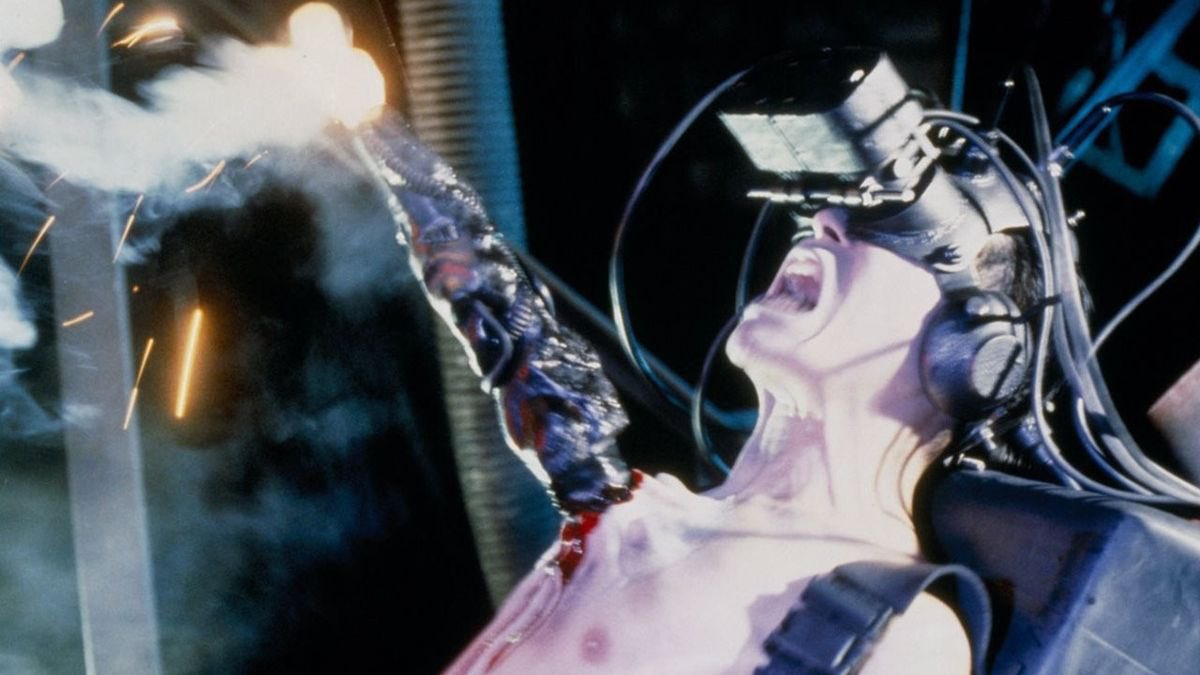

Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992) isn’t so much a follow-up to his monochromatic frenzy of an original as it is a new approach to the same themes he explored in the first go around. 1989’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man is an industrial nightmare – a scouring pad to the grey matter. Body Hammer still retains Tsukamoto’s feverish energy he unleashed in the original film, but it’s in color this time – mostly grim greys and blues with dashes of vibrant orange, but color all the same.

Tomorowo Taguchi once again plays the titular role, this time inhabiting protagonist Taniguchi Tomoo. Taniguch is a mild mannered family man who just so happens to not remember his childhood before the age of 8, when he was adopted. Trying to recap the plot almost seems perfunctory; it’s not the plot we come to a Tetsuo film for, but the chaotic energy of Tsukamoto’s filmmaking. With that said, there is more of a traditional narrative through line in Body Hammer compared to its predecessor.

After Taniguchi’s son, Minori, is kidnapped by a gang of skinheads and Taniguchi is injected by something mysterious, he finds that in his rage and fear he can turn his body into a walking gun. His arm morphs into a canon and a multitude of gun barrels emerge from his chest – which he uses to riddle his enemies into a pulp.

Like the first film, the premise of Body Hammer is inherently absurd and the abrasive filmmaking style can feel like Tsukamoto screaming in your face for 80 minutes while Ministry blasts in the background, but that doesn’t make Body Hammer all punk rock style and no substance. Far from it. Much like its predecessor, Body Hammer isn’t concerned with making sure you’re on its wavelength. It just does its own thing and expects you to keep up.

Underneath the hectic energy, Body Hammer has a lot to say about the darkness of the human heart and the oppressive dread of the modern industrial world. Taniguchi’s powers are at first framed in a traditional action film lens. The hero was wronged, he gets powers, and we want to see him mess up the bad guys real good. As Body Hammer progresses, however, the familiar action film conceits warp into something far more tragic and perverse. As Taniguchi combats the skinhead gang who possess the same powers he does, you quickly realize the traditional narrative trappings of a hero’s rise to power and actualization are in reality latent childhood trauma finally allowed an outlet of escape. As his rage grows, as his memories emerge and revelations rear their head, Taniguchi becomes far more machine than man.

His aforementioned missing childhood memories reveal that his biomechanical power set have been with him his whole life from the abuse and experimentation perpetuated by his father on himself and his brother. At about the midway point Body Hammer transforms from a chaotic quasi-action film into a story of two brothers – Taniguchi and Yatsu (the leader of the skinhead gang) reconciling their childhoods. The comfortable thematic blanket of good guys and bad guys is ripped away, and we’re given a final act that is a clanking cacophony of images and sounds. The editing becomes so erratic, the body transformations become so inhuman, it’s difficult to even discern just what the hell is going on at some points. But despite Tsukamoto’s refusal to play by the rules, Body Hammer never becomes truly incomprehensible. By the end of the film, it actually reaches a certain profound sense of bittersweet triumph.

Tsukamoto is known for his explorations of the hell that is the modern industrial landscape. The Japan of Body Hammer is steely and alienating. The slate blue-gray, skyscrapers seem to take on an almost antagonistic presence as Tsukamoto’s editing constantly interjects them into the film. The camera swoops, dips, dives, twists, turns, and jitters from scene to scene. The relationship between man and metal in Body Hammer has a larger thematic scope to it than The Iron Man. The corruption and seduction of the steel, the rust, the gears, and the girders is generational. It’s in that subliminal space that Tetsuo II: Body Hammer finds its power.

Editorials

‘Immaculate’ – A Companion Watch Guide to the Religious Horror Movie and Its Cinematic Influences

The religious horror movie Immaculate, starring Sydney Sweeney and directed by Michael Mohan, wears its horror influences on its sleeves. NEON’s new horror movie is now available on Digital and PVOD, making it easier to catch up with the buzzy title. If you’ve already seen Immaculate, this companion watch guide highlights horror movies to pair with it.

Sweeney stars in Immaculate as Cecilia, a woman of devout faith who is offered a fulfilling new role at an illustrious Italian convent. Cecilia’s warm welcome to the picture-perfect Italian countryside gets derailed soon enough when she discovers she’s become pregnant and realizes the convent harbors disturbing secrets.

From Will Bates’ gothic score to the filming locations and even shot compositions, Immaculate owes a lot to its cinematic influences. Mohan pulls from more than just religious horror, though. While Immaculate pays tribute to the classics, the horror movie surprises for the way it leans so heavily into Italian horror and New French Extremity. Let’s dig into many of the film’s most prominent horror influences with a companion watch guide.

Warning: Immaculate spoilers ahead.

Rosemary’s Baby

!['Rosemary's Baby' - Is Paramount's 'Apartment 7A' a Secret Remake?! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Rosemarys-Baby.jpeg?resize=740%2C416&ssl=1)

The mother of all pregnancy horror movies introduces Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow), an eager-to-please housewife who’s supportive of her husband, Guy, and thrilled he landed them a spot in the coveted Bramford apartment building. Guy proposes a romantic evening, which gives way to a hallucinogenic nightmare scenario that leaves Rosemary confused and pregnant. Rosemary’s suspicions and paranoia mount as she’s gaslit by everyone around her, all attempting to distract her from her deeply abnormal pregnancy. While Cecilia follows a similar emotional journey to Rosemary, from the confusion over her baby’s conception to being gaslit by those who claim to have her best interests in mind, Immaculate inverts the iconic final frame of Rosemary’s Baby to great effect.

The Exorcist

William Friedkin’s horror classic shook audiences to their core upon release in the ’70s, largely for its shocking imagery. A grim battle over faith is waged between demon Pazuzu and priests Damien Karras (Jason Miller) and Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow). The battleground happens to be a 12-year-old, Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair), whose possessed form commits blasphemy often, including violently masturbating with a crucifix. Yet Friedkin captures the horrifying events with stunning cinematography; the emotional complexity and shot composition lend elegance to a film that counterbalances the horror. That balance between transgressive imagery and artful form permeates Immaculate as well.

Suspiria

Jessica Harper stars as Suzy Bannion, an American newcomer at a prestigious dance academy in Germany who uncovers a supernatural conspiracy amid a series of grisly murders. It’s a dance academy so disciplined in its art form that its students and faculty live their full time, spending nearly every waking hour there, including built-in meals and scheduled bedtimes. Like Suzy Bannion, Cecilia is a novitiate committed to learning her chosen trade, so much so that she travels to a foreign country to continue her training. Also, like Suzy, Cecilia quickly realizes the pristine façade of her new setting belies sinister secrets that mean her harm.

What Have You Done to Solange?

This 1972 Italian horror film follows a college professor who gets embroiled in a bizarre series of murders when his mistress, a student, witnesses one taking place. The professor starts his own investigation to discover what happened to the young woman, Solange. Sex, murder, and religion course through this Giallo’s veins, which features I Spit on Your Grave’s Camille Keaton as Solange. Immaculate director Michael Mohan revealed to The Wrap that he emulated director Massimo Dallamano’s techniques, particularly in a key scene that sees Cecilia alone in a crowded room of male superiors, all interrogating her on her immaculate status.

The Red Queen Kills Seven Times

In this Giallo, two sisters inherit their family’s castle that’s also cursed. When a dark-haired, red-robed woman begins killing people around them, the sisters begin to wonder if the castle’s mysterious curse has resurfaced. Director Emilio Miraglia infuses his Giallo with vibrant style, with the titular Red Queen instantly eye-catching in design. While the killer’s design and use of red no doubt played an influential role in some of Immaculate’s nightmare imagery, its biggest inspiration in Mohan’s film is its score. Immaculate pays tribute to The Red Queen Kills Seven Times through specific music cues.

The Vanishing

Rex’s life is irrevocably changed when the love of his life is abducted from a rest stop. Three years later, he begins receiving letters from his girlfriend’s abductor. Director George Sluizer infuses his simple premise with bone-chilling dread and psychological terror as the kidnapper toys with Red. It builds to a harrowing finale you won’t forget; and neither did Mohan, who cited The Vanishing as an influence on Immaculate. Likely for its surprise closing moments, but mostly for the way Sluizer filmed from inside a coffin.

The Other Hell

This nunsploitation film begins where Immaculate ends: in the catacombs of a convent that leads to an underground laboratory. The Other Hell sees a priest investigating the seemingly paranormal activity surrounding the convent as possessed nuns get violent toward others. But is this a case of the Devil or simply nuns run amok? Immaculate opts to ground its horrors in reality, where The Other Hell leans into the supernatural, but the surprise lab setting beneath the holy grounds evokes the same sense of blasphemous shock.

Inside

During Immaculate‘s freakout climax, Cecilia sets the underground lab on fire with Father Sal Tedeschi (Álvaro Morte) locked inside. He manages to escape, though badly burned, and chases Cecilia through the catacombs. When Father Tedeschi catches Cecilia, he attempts to cut her baby out of her womb, and the stark imagery instantly calls Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury’s seminal French horror movie to mind. Like Tedeschi, Inside’s La Femme (Béatrice Dalle) will stop at nothing to get the baby, badly burned and all.

Burial Ground

At first glance, this Italian zombie movie bears little resemblance to Immaculate. The plot sees an eclectic group forced to band together against a wave of undead, offering no shortage of zombie gore and wild character quirks. What connects them is the setting; both employed the Villa Parisi as a filming location. The Villa Parisi happens to be a prominent filming spot for Italian horror; also pair the new horror movie with Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood or Blood for Dracula for additional boundary-pushing horror titles shot at the Villa Parisi.

The Devils

The Devils was always intended to be incendiary. Horror, at its most depraved and sadistic, tends to make casual viewers uncomfortable. Ken Russell’s 1971 epic takes it to a whole new squeamish level with its nightmarish visuals steeped in some historical accuracy. There are the horror classics, like The Exorcist, and there are definitive transgressive horror cult classics. The Devils falls squarely in the latter, and Russell’s fearlessness in exploring taboos and wielding unholy imagery inspired Mohan’s approach to the escalating horror in Immaculate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.