Interviews

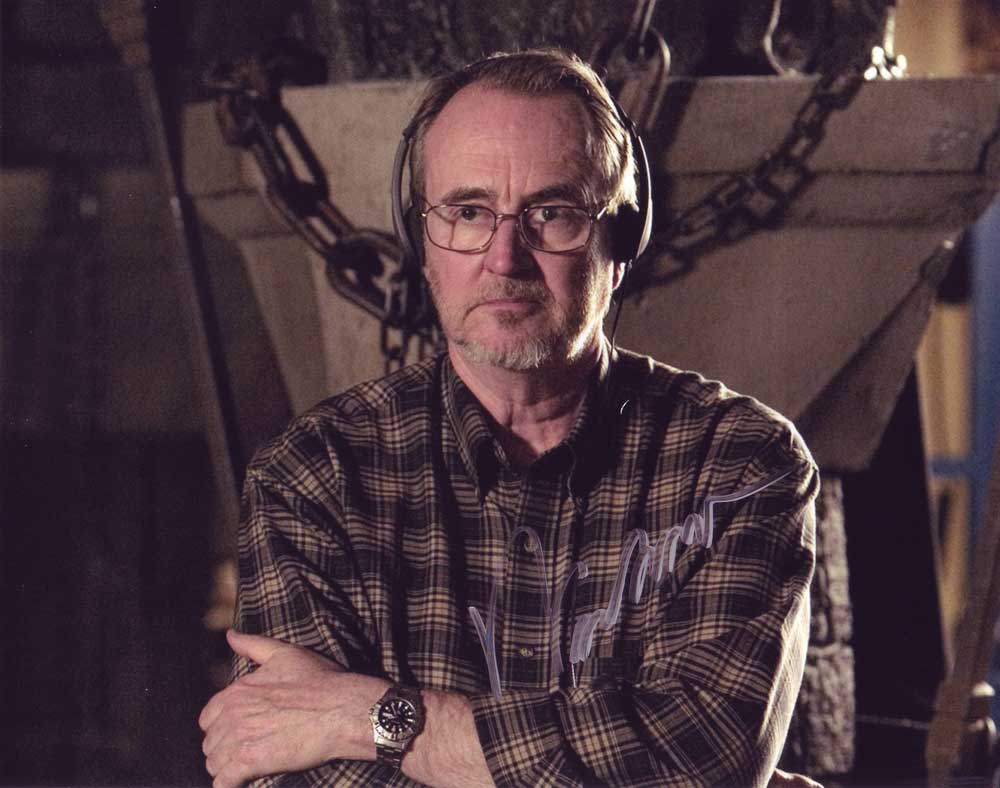

Wes Craven Looks Back on ‘Scream’ Franchise

As you all know, Wes Craven is out in Michigan shooting Scream IV, the latest installment in the slasher franchise arriving in theaters April 15. Bloody Disgusting music contributor Jonathan Barkan (and a few of his classmates) were lucky enough to spend an afternoon with the horror icon, where they talked about all sorts of things ranging from his style of horror vs modern horror to his 3-D conversion of My Soul to Take. Read on for the intimate interview.

This past summer semester, I took a course at the University of Michigan entitled, “The History of Horror After Psycho”, taught by Professor Mark Kligerman. The class was truly an intimate experience, with there being only 15 or so students. Apart from being an amazing class where we got to watch gorgeous prints of classic films, such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Exorcist, Alien, and other “must-see” movies, we discussed the impact of social, gender and political occurrences on the horror films of the time. How the so-called “living room wars” during Vietnam affected 60’s and 70’s horror, the rise in Canadian horror (especially in reference to Cronenberg), the role of women in horror, both as victim and as the “final girl”. This was by no means an easy course, but it definitely affected my view of horror films and will constantly force me to challenge what I see and look beyond the first few layers of veneer to find the gritty underbelly.

Although the semester was over, on Saturday, August 21st, we got the opportunity to watch a beautiful 35mm copy of Scream whereupon afterwards, Wes Craven came in for a casual Q & A. The focus of these questions was not to find out about ‘Scream 4’ or ‘My Soul To Take’, but rather to hear the thoughts of the legendary director on how horror has changed over the years and how he approaches his films. Check after the jump for the incredibly in-depth responses from Wes Craven.

Over the history of horror, what does it take to viscerally affect a viewer and is there a difference between what it took in the past versus now?

Wes Craven (W.C.): Well, I found that in order to viscerally affect someone, you need to cut them [laughs]. Well, everyone says “How many gallons of blood do you need for a horror film?” I never find it’s that. Yes, you can have a scene that’s very violent but I find that if you have something that gets under the skin of the audience in other ways and that usually has to do with the more human side of it, even with Last House (on The Left).

And doing something that’s not expected within the genre. When I shot Last House, when you got shot or stabbed, you fell down dead. I just did the opposite: Somebody gets stabbed and they fall down but then the killer is ready to walk away and the person starts crawling. Nothing is as fast as it’s supposed to be in a movie where people are supposed to die. That kinda started a whole different thing.

But it has to do with making people real, I think more than anything else. You can have a movie where you kill people by the billions and it will become like Stalin says: “One person dies and it’s a tragedy. One million people die and it’s a statistic.” So it starts to lose the effectiveness unless you feel those are real people.

And just being different that anything else that people have seen before, also. We just killed somebody last night that way.

[laughter]

But literally, I had a scene where somebody was going to be killed and it was described as, well, an incidence; he’s pinned to a seat, he’s in a car. That’s it? That’s what happens to a character I’ve been watching for 45 minutes? So I just really ask myself, all the time, “Have I seen this before? If not, what would be really fascinating and different? And would it be something that I would want to see? Would it grip me? Make me scream, or laugh, or something like that.”

I think, bottom line, the advice I would give is don’t duplicate what you’ve seen before. That seems to be the primary mistake that young filmmaker’s make. They’ve seen every film in the world. I think one of the gifts that I had was that in a Church and a college that was very strict and it didn’t allow seeing movies at all, so I didn’t have any precedent. So, when I made movies, I didn’t copy anything because I hadn’t seen anything! [laughs] Certainly nothing in the genre. So you have to keep your head up and ask, “Have I seen this before and if I have, go someplace else. Do something different.”

Do you think that realism has a more visceral impact as opposed to something not as realistic?

W.C.: Yeah, but nothing in Shakespeare was real but it has enormous impact. It’s lasted for centuries, so it has to do with an underlying reality that there is something human about it that you recognize. And that can even be in ‘Scream’. I think what Kevin Williamson captured, and that maybe I enhanced a bit, was that it’s funny and it’s sort of arch and it’s comedy on the culture and everything else and self-referential, so you get to like Randy. You get to feel like he’s a real person. And certainly with Neve Campbell’s character. That’s kind of a real person and you invest yourself into that character a lot more if it’s real. So I think that even within the context of the film, it is clearly referring to itself as a member of the genre, you know? [laughs] You can still make a reality there that enhances the impact of things, to frighten or just to make you laugh.

Personally, I don’t enjoy going to see a lot of horror films because it’s usually just, sort of, two-dimensional characters getting slaughtered. And I just don’t have any interest in that. But if it’s a situation of a person where I think, “Oh my god, I would do that!” It’s like thinking, “Don’t go outside.” We had a character in Scream 3, an African-American, who at some point said, “This is where all the black characters get killed! [laughs] I’m outta here!” And he leaves the movie, you know? And you never see him again.

[laughter]

So, it’s doing the unexpected. It’s always a lot of fun and it makes things fresh. I sometimes tell students that the first person you should make the audience afraid of or uneasy with or watching, as far as monsters or scary characters within the film, is the director. They have to feel like whoever made this movie is crazy and smart is one step ahead of me. That’s kind of your responsibility, not to underestimate your audience but to really be as smart and unpredictable and ahead of the audience as you can be. And to make your character smart and unpredictable. And especially your villains.

‘Nightmare on Elm Street’ went around Hollywood for three years and was rejected by everybody as either “too bloody” or “too stupid” or nobody would believe what was going on because it was in a dream or nobody would be afraid of it because it was in a dream. The audience was way ready for it! So, a lot of getting a good script going is finding a way past the studio blockade of people who can’t understand how it will really play. And I deal with that all the time. You feel like, here’s you guys (the audience) and here’s this wall called the studio or a person in the studio. How do I get my film through that little aperture there that the studio allows you sometimes, to get to the audience and talk to them? Because the typical thing is, “This is stupid.” or “I don’t understand this. This will never play.” Because there are quite often people who don’t and sometimes aren’t even that invested into the genre, they’re just invested in the money that the genre can make.

Now, that is changing a lot. I mean, I think starting around ‘Red Eye’ I certainly walked into Dreamworks where the meeting was and pitched my idea and my script and everybody stood up and said, “I watched Last House on the Left when I was 13 and that’s why I’m in the business.” That’s a huge change! And there are a lot more people at the studio level that are real fans and know the genre and are smarter about it. But you still run into it a lot. I think that’s true with any idea. You look at Edison or any person with an idea that’s ahead of its time. That’s something of a curse. People are congratulating me now for making ‘Last House on the Left’ that when I made it were looking at me like I was a sick mother [pauses for effect]

[laughter]

And they kept their children away from me! I’m serious! [laughs] And so I was just commenting on the times as I saw it. But nobody was doing it like that, nobody was being that blunt about it.

In your movies, you display a lot of alternative families: In ‘Last House on the Left’, you had the very dysfunctional family of Krug and company and you also had Nancy’s family in ‘Nightmare on Elm Street’ and you had the kind of unit in ‘People Under the Stairs’. It’s a common theme that I’m seeing throughout your movies. Do you think that because the heroes of the stories are the product of these alternative families, is there the idea of a generation growing up with more strength because of this lack of normalcy?

W.C.: No, I think you guys are all screwed up.

[laughter]

It could well be. With the sort of tsunami of media that started somewhere around the Vietnam War where suddenly everyone was seeing real life almost thrown on their television every night, with documented footage of the Vietnam War and the revelations about the presidency and having electronic ways of retrieving information from the government. A typical teenager knows a lot more about how the world really works. And it just keeps expanding: I remember my son telling me, “I watched this guy get his head cut off on the web.” And shit, my little boy! [laughs] He was a young man at the time but that was when Al Qaeda was capturing people and cutting their heads off and putting it on the Internet so that generation was exposed to just hideous things that are real that they have to process. And I’ve always felt that horror films are the nightmares of the culture and that nightmares, as a function of the organism of human beings and of the mind that human beings have, they’ve kept nightmares, evolutionary-wise. So, I’d say that horror films fall into that in terms of cinema, as the nightmares of the culture, things that keep us awake at night. Whether it’s ‘Frankenstein’, what science is starting to do, fooling around with human beings and being able to control people’s minds and so forth, or atomic energy in the 50’s with all those horror films, or serial killers and mass murderers. It’s all reflecting the culture. And I’ve always felt that people who criticize horror films are trying to break the mirror.

Where did the conception of the personality of Freddy Krueger come from?

W.C.: Well, it’s kind of an old story, so I’ll abbreviate it. There was an adult, a drunk that happened to be walking by the apartment I was living in with my family when I, I don’t know, 12, or something like that. He woke me up out of sleep with drunken rumblings and when I looked out, I was in the second story bedroom, he somehow stopped and looked right up at my window. I backed away from the window and sat on the edge of my bed, scared. There was something about the way he looked at me. I thought I was there for a year and then I finally crept back to the window and he was there and he did this (makes a scary face) and then he kept walking down the street, looking at me, sort of over his shoulder. Then he went into our building and I knew he wasn’t from our building. So that, in retrospect looking at it as an adult, I realize that was somebody getting a sense of power and enjoyment out of terrifying a child and having power over that child’s mind. That never left me, that sense of there are people out there who will enjoy your suffering and sometimes they have more power than you do.

So, it was kind of based on that and also little things; that man wore a hat and Freddy wore a hat. The hand claws were simply two things. One; that was a time when there were a lot of villains with masks and knives or machetes. There was Jason and others. So I asked myself, “What haven’t I seen?”, that was the question I referred to earlier, and I literally went through my memory of what I thought was the earliest sort of DNA structures of human memory of fear. I went back to cave bear and claws and the idea of the tooth and claw, because that has to be buried somewhere very, very deep and that’s gotta be what knives are. I remember walking around London and the royal palaces there and all the fences had swords and that’s part of their fence railings. It’s just this sort of idea of the edged weapon and the thing that skewers you. It’s very deep in our culture and I think that comes from out genetic part of ourselves.

And the human hand: I remember reading that one of the reasons that the brain grew so much is because of the opposable thumb development and what you could do with it. The fingers and brain fed each other. The more the fingers could do, the bigger the brain had to be to handle what the fingers could do and vice versa. So you end up with this creature that has this incredible dexterity. So, the hand as a weapon itself is intriguing.

So part of it was intellectual, psychological, I was a psychology major, art minor in college, so I’m fascinated by nature. So, it’s a whole host of things, kind of being put together.

You say that horror movies are often a commentary of the social events of a time. How do you feel that ‘My Soul To Take’ and ‘Scream 4’ are reflections of current social events?

W.C.: Well, two different things: ‘Scream 4’ is very much about of analyzing the culture of violence and film. It’s been basically 10 years since a ‘Scream’, so that part of it, the Meta part, that standing off and looking at the culture, sort of analyzing it, that’s the subtext of ‘Scream 4’, among other things.

‘My Soul To Take’ was part of, going back to talking about families, was somewhere in the course of my career, I realized that some of my best films were about families of some sort. Also, opposing families and if you look at history, it’s all about opposing families: Royal families, human rights, human families versus animal families and all sorts of things like that. So I found that I just sort of instinctively did films about families and that they were very powerful and to me it was intriguing because you get to look at two or three generations, like ‘The Hills Have Eyes’ where you have the older parents, the father with the gun and then you have the mother, practically nursing her child and then you have the younger child, the baby itself, symbolizing innocence. That sort of tribe and levels of generations and worldviews and all these things that I found really interesting, and missing from a lot of horror movies as well.

Like ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre’, which is one of my favorites, it’s just a bunch of kids but you have the family on the other side and that was really where I found it very intriguing. And even Hitchcock: ‘Psycho’ with the son and mother.

So those are very, very powerful things in all of our lives and that’s kind of how I ended up there, that’s why ‘My Soul To Take’ is commenting about. It’s the question of “Who were, or are my parents?” especially if they’re gone. “What do they do and what grief is it bringing down on my head?” And then, the question you ask yourself, just a few years later, is “Am I going to be like that?” or “Am I like that?” So there’s always this thing as you’re going from high school to college where all the adults are fucked up and they’re responsible for all the wars and blah blah blah. Then you find yourself with your first child, saying something that you remember your parents saying or you’re marching off to war or whatever it is, and it’s then that you realize that it’s kind of this wheel going. It’s very interesting to look at from multiple generations sometimes.

But anyway, ‘My Soul To Take’ is about that. And it’s based on a legend from a Native American legend about condors, because the central character loves birds, especially the California condor, which is kind of clinging on the brink of extinction, about the gatherer of souls and that it’s not a hideous creature that eats dead things, as the high school principle of this young man says, but it is something that keeps the soul of every animal that it eats and protects it, so that it has accumulative wisdom and gravity about it. It’s kind of fun. [laughs]

[laughter]

You’ve been making horror films for a long time and the genre has obviously changed so much in that time. There is a lot of films that use the extreme, such as the so-called “torture porn” films of Eli Roth. Do you feel that you have to keep up with or top those films? Do you feel that audiences are so jaded these days that it’s harder?

W.C.:No, I feel like the audience is bored, like they’ve had enough of it. Like, “Is that all you’ve got?” In fact, that’s one of the things I guard myself against, is never trying to emulate. The few times that I’ve tried to do this have been quite disastrous [laughs]. I personally don’t like the “torture porn” stuff. I watched ‘Saw 1’ and, okay, that was kind of interesting, but it’s just not my cup of tea, so I don’t try to emulate it. Not to say that they’re bad films or anything, unless they get into the 7th and 8th and 10th iteration, then maybe.

[laughter]

Look, we’re doing ‘Scream 4’, so…[laughs]

[laughter]

As long as you keep it fresh!

But ‘Scream 4’ won’t be like that?

W.C.: No. But ‘Scream 4’ is unique. I can’t think of another film that is a tracking of three central characters over a span of 16 years now, with the same actors. You’re literally watching someone go from high school age to full adulthood, with Neve Campbell for instance.

And what’s that vampire movie from Scandinavia. ‘Let the Right One In’? That’s a pretty fascinating film. So, throughout all generations there’s great original films.

I’ve always thought that Nancy Thompson from the original ‘Nightmare on Elm Street’ is the quintessential “survivor girl”. I feel that the evolution of this character, who makes the decision to stand and fight has evolved into something along the lines of “torture porn”, where as long as we see the girl fight, that’s enough for us. Is that something that you are still trying to cultivate? The idea of a very strong woman who is trying to face the fears that keep following her?

W.C.: Well, I’ve done a lot of central characters that are female and strong. I have a daughter, who now has her own child, and it was after ‘Swamp Thing’, in a scene where Adrienne Barbeau is running away from the bad guys and she trips and falls down. And my daughter turned and looked at me when she saw that and said, “Dad. Women don’t always fall down when they’re running, okay?”

[laughter]

[laughs] And I really got it! I just got it! So then I went off and did movies about strong female characters. But ‘My Soul To Take’ is Max Theriot, he’s the central character, so it’s not always that.

There is something inherently…how to say this without sounding sexist? But there is something inherently more vulnerable about women in that they are usually a little bit smaller and a little bit more sensitive to things than men, so they quite often get put into situations in horror films or action films. But the interesting thing is that they have become very strong. Look at the character in ‘Terminator’, who when one of the first times you see her, I think it was in ‘Terminator 2’, she’s in the jail cell doing pull-ups and you see these actual muscles on an actual actress that didn’t have them before and you realize there’s a whole different way of looking at femininity that has arrived and is actually being assaulted on all sides by pornography and the popularization of “the pimp”. You know, it just makes my blood boil because it’s just trying to beat back women. It’s quite insidious. There’s a very powerful backlash going on. It’s a battle of centuries and centuries, all over the world, as I’m sure you know. Women are really subjected to being under the thumb and foot of men, so it’s a very important struggle. So I like showing female characters that can stand up and fight through no matter what.

When I saw ‘Saw’, or maybe it was ‘Hostel’, I really felt it wasn’t as bad as I thought, because at least the characters got away, but you can also have filmmakers like the German guy, what’s his name? Where in ‘Funny Games’ you have the woman pushed off the boat and she drowns, and it’s just like “Okay.” And with making films you can constantly decide anything you want to happen. So then what do you want to say about life or what do you want to put on the audience? You could center a film around something awful, hideous where everybody dies in the most hideous, novel way and say, “That is the truth.” But there’s a lot of truths, you know?

There’s just a lot of different things that occur in the human family, so at a certain point, I think ‘Last House on the Left’ was as far as I would go with bleakness. And I’ve always asked myself, “Am I selling out?” You know, ‘Scream’ people are laughing when someone is getting stabbed and everything else. But I’ve always tried to keep a core of reality in the Neve Campbell character. She actually feels the loss of people. I guess, in a sense, I feel that’s where I am in what I do for a living. This odd job or odd career of doing horror films, which I never expected to get into. It’s just pure chance. I continually wake up and say, “What the hell? I can’t believe I’m making horror films!”

[laughter]

Right now, in the horror genre, there are a great deal of sequels and remakes, especially with a lot of your older films. It seems like the fans wanting some original content, which ‘My Soul To Take’ will offer. But how do you think that ‘Scream 4’ doesn’t fall prey to the victim of “another sequel”?

W.C.: Well, the biggest thing about it is that’s exactly what it talks about. We’re all sick of sequels and what is the new genre of cinema and horror going to be? Of course, the plot is wrapping itself around what it will hopefully be, in the vision of Kevin (Williamson). It takes that on head-on; it’s all about that. Where do films go from here in the genre? What will make them different and not just more sequels or remakes?

I have to say, in defense of the two remakes, or three, ‘The Hills Have Eyes’ and ‘Last House On The Left’ were unique. As you know, they were the first two films that I had made. They were made with two separate buddies, just friends that I had gotten to know in New York when I’d first just gotten in. We had in our contracts, which we were joking about; we were longhaired freaks doing lots of drugs and convinced we would be dead by 35. And at a certain point, we realized, “Oh my god! I think we own that property again!” 30 years later, so that’s when we decided to start looking around, start talking to interesting directors to see if they’re interested in doing a remake. So ‘The Hills Have Eyes’, ‘The Hills Have Eyes 2’ and ‘Last House On The Left’ came out of that. It gave me a chance to work with my son, he was producer on it. And at the same time, it was scary. I was afraid of burying myself, of having people say, “I love ‘Last House On The Left’!” The one two years ago [laughs].

[laughter]

“You mean there was an earlier one?!” [laughs]. So, you do run that risk.

With ‘Nightmare On Elm Street’, unfortunately though, because nobody else wanted to buy it, when I did sell the script, it was, you know, New Line Cinema, which at the time was working out of a store front, the contract was that they owned it forever and ever. And so I didn’t even have a phone call to me on that one. It was just whoever did it, did it.

But ‘Scream 4’ is about that. And at the same time, I have to say it was a joy to have Andrew Rona, who was the executive at Dimension just under Bob Weinstein. I worked with him throughout all the ‘Screams’ and then he eventually left Bob Weinstein and went and to Rogue films, before it’s current Rogue films. And then he offered me the chance to write something if I had an idea and I pitched him the idea and it’s the first film that I’ve written and directed, with the exception of that little 5-minute thing in ‘Paris, Je T’Aime’, since ‘Wes Craven’s New Nightmare’. And I don’t know how the hell that happened! I think between ‘Scream’ and ‘Music of the Heart’ and ‘Red Eye’, I just had good scripts available, so I did them.

And as hard as it is to be a director, it’s even harder to be a writer-director, because you do all the director’s work until two or three in the morning and then [laughs] you start the re-writes and then work until five and then get up at six, so it’s hard, but it is your personal baby and that’s great.

Since you’re post-converting ‘My Soul To Take’ into 3-D, what is your take on the current 3-D craze going on in Hollywood right now?

W.C.: That’s a good question. It’s been a long trek to get it finally coming out. That said, all of that done, we finally have the film done and Relativity is finally gearing up and I get the call of, “You know, we want to do it as 3-D.”

Somebody that’s working with me that started as my assistant and is co-producing with us on this film researched very thoroughly and we started going to places that would do the process if we were to do it. And this is not a film that is shot in the two-camera, old way of doing things, but there’s a new system where basically, you take a film that was shot in 2-D and you feed it through giant computers and assign distances for every single thing in the frame then there is a sub-computer system that rounds the characters and others that deal with hair. I mean, it’s an incredibly complex thing. It’s a lot of handwork and all the math involved.

I went to see ‘Clash of the Titans’ at the place that made it, after reading all the reviews and Roger Ebert saying that “3-D was the worst thing to come out of the pipe, ever.” and that for the filmmakers it was a tragedy that had been forced into it. In the place that made it, and showed it properly, ‘Clash of the Titans’ was fantastic. Clear, no problem seeing it. Much more 3-D-ishness then I would prefer. At the same time, I was getting educated in on the enormity of the push towards 3-D by people at top of manufacturing television sets and equipment that shows movies, exhibitors. As far as I can tell, it’s here to stay, in a huge new way. I mean, there are 3-D television sets that are just around the corner, probably already in stores at a high price. And someone at the studio told me that, “You, now, are at the brink between silent films and talkies.” So there were people back then that were fantastic in silent films and that decided that talkies were horrible and they were not going to go there. Then there were others that made the bridge.

I decided for the sake of my film and for what I’d seen in that theater, it was looking pretty good. It was also with an understanding with the studio that I wasn’t going to make it with things flying into your face, especially since the film was already shot. We were going to use it subtly and kind of make it in the way that the eye actually sees things. It was worth a shot and the film would get out there and it would also be out there in 2-D. We’ll see what happens. I hope I haven’t sold my soul!

It’s interesting because there is one character in the film that is quite insane and it kind of comes on slowly, but within the span of a single scene. As a director, you can make that room start to distort very subtly in the course of a three-minute scene. You have another palette that you didn’t have before. I’m trying not to throw it out because it’s new and see what happens.

…There is an infrastructure that is very important at the level of theaters where it takes something like eight times as many lumens to push through the film in 3-D because you’re looking through glasses. So you need extraordinarily bright projections. There is still the option for theater owners to put the bulb at half lumens so it’ll last almost twice as long and the bulbs cost like $3,500 a piece. So there is always a problem at the level of the theater itself where they are pinching pennies and then it’s dim and everyone says “3-D sucks!” but it’s not that, it’s the manager. I think it was ‘Alice in Wonderland’, that studio did a quality check at every single theater it played in. So that’s what I think it will take, at least in the first two, three, four, five years before people catch up. But I can tell you that I’ve seen my films in 2-D back in the day, you know, coming fresh from the mix two weeks before when you go opening night, and there’s a broken speaker in that theater and that guy is running it at half-lights and they have lights for people to walk up and down the aisles and it’s like you just want to blow your brains out anyways.

[laughter]

So, in Los Angeles, there’s a theater called the Arclight. The whole thing about it, you pay more, much more to see a film but it’s perfect projection. Nobody is texting. You go in there to see a perfect quality production and it’s a great thing and that’s what it takes.

Thank you all for the great questions!

Interviews

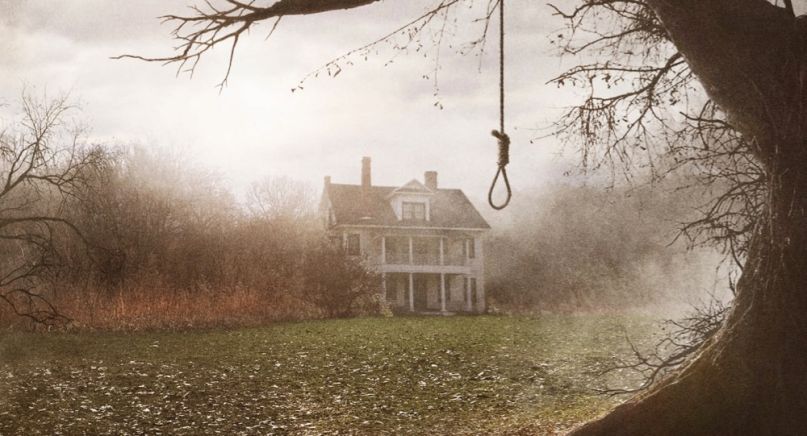

“Be Not Afraid”: Andrea Perron Shares the Chilling True Story Behind ‘The Conjuring’ [Interview]

Welcome back to DEAD Time. I hope you left a light on for me because this month we’re going inside The Conjuring house to find out the real story of what happened to Carol and Roger Perron when they moved their five daughters into a house in Burrillville, Rhode Island in the early 1970s.

In 2013, director James Wan unleashed the terrifying horror film The Conjuring, which was based on the case files of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren and told the story of a family tormented by a demonic force after moving into their new home. In real life, the Warrens did investigate the activity in the Perron home, but the story goes a bit differently. You may think you know what really happened inside that house based on the horror movie alone, but you would be mistaken. The true story is much, much scarier.

Bloody Disgusting was delighted to have the opportunity to chat with Andrea Perron, the oldest of the five Perron daughters, who was witness to the paranormal activity in the family’s home. Andrea is a lecturer and the author of the trilogy of books, House of Darkness House of Light, which tells the story of what her family experienced while living in the house in Rhode Island for a decade. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Bloody Disgusting: Your family moved into the old Arnold Estate in 1970, correct? How long after you moved into the house did your family begin to experience unusual activity?

Andrea Perron: We bought the house in December of 1970, but we didn’t move in right away because my mother didn’t want to move during Christmas. My mother found the farm for sale and our family went to the farm a number of times and we loved it and we all felt like it was home to us. It was an original colonial home and a farm and 200 acres of land it was a big deal. My parents paid $72,000 for the house and back in 1970 that was a lot of money. All of the times we visited the house with Mr. Kenyon, who was the owner, none of us remembered having anything strange or otherworldly or mystical happen. We just enjoyed the property and the land, and the place itself was just so incredibly enticing. None of us have any memory of seeing anything strange or weird there until the day we moved in. It was as though the spirits were all just holding their breath [laughs] waiting for us to get there and live there.

The first thing that happened was my father opened up the back of the moving truck and handed me a box. We were in the middle of a snow and sleet and ice event, and the wind was whipping around, and it was freezing cold. I went into the nearest door with the box that was marked kitchen and my mother had already come in with my baby sister April and had gone into the kitchen. April was only five, she was too young to help unpack or help unload boxes, so she just stayed with mom. I walked into the parlor and took a right into the living room and Mr. Kenyon was packing a box of his wife’s china. I stopped and started chatting with him and then I picked up the box and turned to go into the kitchen through the front foyer, and there was a man standing there that I thought was oddly dressed. He seemed like flesh and blood to me to the extent that as I walked past him, I said, “Good morning, sir.” I didn’t see him when I walked into the room, but he was standing in the corner of the door when I picked up the box. So, I walked into the kitchen, and I remember asking my mother who that man was with Mr. Kenyon. Her response was, “There’s nobody with Mr. Kenyon. His son is on the way, but he’s not here yet.” So, I’m sure at the age of twelve, I assumed that a neighbor had stopped by, and my mom didn’t know it.

I went back outside to the moving van and meanwhile, my sister Christine walked in, and she saw him and walked into the kitchen and asked my mom the same question. Mom was busy; she had discovered that Mr. Kenyon had not packed anything in the kitchen. So, Christine asked who the man was. Then my sister Cindy walked through with her box, and she saw him and asked mom about the man that was with Mr. Kenyon and made some comment that he was dressed funny. Then Nancy walked in behind Cindy and said, “Cindy, did you see that man with Mr. Kenyon? I did, but he just disappeared.” That was our introduction to the farm, and it all happened within the first five minutes. Right before he left, Mr. Kenyon asked my father to go for a walk with him. He said to my father, “Roger, for the sake of your family, leave the lights on at night.” My father didn’t know how to interpret that statement. In his mind, Mr. Kenyon was saying that we were moving into a new house with one bathroom on the first floor and the girls would be sleeping upstairs, and that he should leave lights on, so the kids don’t go tumbling down the stairs in the middle of the night. That’s how he interpreted what Mr. Kenyon said to him. Over the first few months we were living there, we were told by various people in the area that there was never a time when it was dark outside that every light in the house would not be on.

BD: I read that you described the house as “a portal cleverly disguised as a farmhouse.” What led you to believe the house was a portal?

AP: It wasn’t just the house, it’s the property. The barn is as active as the house is. And the property is as active as both the house and the barn. There’s an awful lot of elemental activity. There’s tons of extraterrestrial activity there. And I think it has something to do with the fact that the farm is built on top of an ancient river which was lost during the last Ice Age. It’s known as the Lost River of New Hampshire, but it actually runs all the way underground. It’s buried about 700 feet underground. And on certain days when the water is very heightened and rushing, you can actually feel the vibration of it in the land. And you can lay on the stone walls and feel the stones vibrating from the river rushing underneath our feet. And it goes directly underneath the farm, but also there are two creeks or tributaries to the Nipmuc River, which runs right along the bottom of the property just beyond the stone wall that marks the backyard. So, the river is maybe 700 or 800 yards away.

I think it has something to do with all the water that it is surrounded by. Somebody sent me a drone shot of the farm from high enough up that it was probably, the drone was probably at least 3,000 feet. And it was the most interesting photograph that I have ever seen of the farm because from the angle that the shot was taken directly over it, it looks like a pyramid in the middle of a forest.

BD: Do you have an idea of how many spirits or entities you were dealing with in the house?

AP: Well, I can tell you that there were at least a dozen of them that we were very familiar with that we saw over and over and over again. Another interesting thing too is that the, none of us had any fear of this spirit that we saw that first day moving in. It was, it was not that kind of a vibe at all. In fact, he appeared to be very sweet-natured and cheerful, and he was really focused on Mr. Kenyon. But within the first couple of nights that we lived there, my sister Cindy came crawling into bed with me and she was obviously upset. She was only eight years old and asked if she could sleep with me. And I said, “Of course.” Then I pulled back the quilt and she hopped down.

I’m like, “What’s wrong?” And she said that she could hear voices in her room. Well, the upstairs of the house, every door opens into the next bedroom. And we had all of the doors open because the house was cold and that was the way, you know, to keep the heat moving instead of being trapped in one room or the other. And it was a new house to us even though it was 250 years old. And so, we always left the doors open between our bedrooms. And when she came in, she kept saying, “I hear voices. There’s voices in the room and I’m scared and it got louder and louder. I can’t believe you didn’t hear it.” I can’t believe it didn’t wake you up.” And at first, she was at that time sharing a room with Christine. And my sister Christine has a tendency to talk in her sleep from time to time.

So, I think I just assumed that Chris was doing that. And I asked her, and she said, “No, it’s not me.” She said, “It’s a whole bunch of voices and they’re all talking at the same time. And they’re all saying the same thing.” So naturally I asked her what they were saying, and her response was, “There are seven dead soldiers buried in the wall. There are seven dead soldiers buried in the wall” over and over and over. And she said all the voices were what you would describe as monotone, even though she did not use that word. She didn’t know that word at that time. But she said they all sounded the same. Like they were all talking together, and they all had basically the same voice. And they were all saying the same thing at the same time. And they were all around her bed to the point where the floorboards were shaking. The bed was shaking. And she put the pillow over her head to try to muffle the sound. And when it became so loud that she couldn’t tolerate it anymore, that’s when she jumped out of bed and ran into my room and got in bed with me. And about three years ago, the house, I mean, nothing could be buried in the walls of the house because the house is just clapboard with horsehair plaster. That’s it. There’s no insulation. There’s no, you know, there’s some eaves that go up under the roof line. But there’s just, there’s no place that bodies could have ever been stored or hidden.

So, it didn’t make any sense. But over the years other people speculated maybe there’s someone buried out near the retaining wall behind the house or down around the stone walls. And so, the previous owner, not the woman that owns it now, but the previous owners had some people come in with ground penetrating radar. And sure enough, they found seven distinct anomalies under the stone wall at the bottom of the property just before you go into the cow pasture. And because it is illegal to exhume anything in the state of Rhode Island, all they could do is offer the photographs as evidence. But there it is. There are seven distinct images that are buried just behind the stone wall on the side of the cow pasture. And that’s where they found whatever they found. But when you consider that that house was completed as it stands now in 1736, the property was originally deeded in 1680. And the house was finished as it is now 40 years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. And so, it really is truly an original colonial home. And it survived the Revolutionary War.

It survived the door rebellion. The King Phillips War, the Civil War. And at the time of the Civil War, the owners, and it was all through marriage. It was eight generations of one extended family that built and then lived in the South for hundreds of years. And we were the first outsiders. We have absolutely no familial attachment to the Richardson family or the Arnold family. And that house was passed through marriage because at that time women were not allowed to own property. So, through marriage it became the Arnold estate, but it actually is the Richardson Arnold homestead.

The Real ‘Conjuring’ House – Photo Credit: Visit Rhode Island

BD: At what point did Ed and Lorraine Warren become involved? There were a few things I read that made it sound like they just showed up at your house because they’d heard about the case.

AP: Yes, they really did. They just showed up at our house. Just one day they just showed up.

BD: So, your family had no idea they were coming?

AP: Well, it’s actually a little bit more complicated than that. We’d already been there for about two and a half years. A group of college students came to the house. Keith Johnson and his twin brother, and some of their friends, were paranormal investigators. And Keith said that my mother had called him and asked him to come check the house out. And my mother said, “I never called anybody.” I never told anybody other than our closest friends about the activity in the house.” Our attorney, Sam, knew. Our babysitter, Kathy, knew. And my mother’s friend, Barbara, knew. And she can’t remember anybody else that she ever said a word to about it. It was a very taboo subject back then. And, yeah, nobody wanted to open Pandora’s box. It was way more than a can of worms. It was just not something that people would talk about except for some of my peers at school, kids that had grown up in that town and knew the reputation of the house, which we were never warned about before we moved in. But, you know, I guess the best way to look at this is that the college students that came, we will never know why they showed up. Keith said my mother called him.

My mother said, “I never called anybody.” But there was some reason, and this is a spirit thing. There is some reason that he was drawn to that house and brought his team and had such extraordinary experiences on the one afternoon that they spent there that he sought out. Ed and Lorraine Warren, he and his team sought them out. They were speaking. His team was from Rhode Island College, and the Warrens were doing a lecture in the fall of that year at the University of Rhode Island. And they told the Warrens about our predicament and where we lived and who we were. The Warrens came the night before Halloween in 1973. It was either the night before Halloween or the night after Halloween. When they showed up at the door, my mother let them in the house. It was freezing out and she offered them a cup of coffee and presumed that they were lost because the farm is very remote. And then they identified themselves. My mother had absolutely no idea who they were. She had never heard their names before. And Mrs. Warren walked over to our old black stove in the kitchen, and she put her hand over her eyes and her other hand on the corner of the stove and became very quiet. And she said, “I sense a malignant entity in this house. Her name is Bathsheba.” Now, Mrs. Warren knew absolutely nothing about the history of the house or the area. Nothing. And she plucked that name out of thin air.

Bathsheba Sherman never lived in that house. She lived at the Sherman farm, which was about a mile away. There were only a few homesteads in the area at that time. She was born in 1812 and she died in 1885. And there were stories that she was in that house and had an infant in her care and that the baby died. The autopsy revealed that a needle had been impaled at the base of its skull and it was ruled that the baby’s death was from convulsions. My mother only found one article about it and it was stored in the archives of Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. She read about an inquest in the town of Burillville, Rhode Island. So, there was apparently a hearing in the neighboring town of Gloucester. And apparently there was an inquest and Bathsheba was questioned by a judge about her involvement with the death of the child. And apparently, she was very convincing that she had absolutely nothing to do with it. So it never went to a jury. There was never a formal indictment. It was let go and she was dismissed from the inquest. But in the court of public opinion, this young woman who had just married Judson Sherman was tried and convicted in the court of public opinion. And there were all kinds of accusations and innuendos and rumors that circulated around her for years and years, all the years of her life, that she had something to do with it.

Oh my God, if you were to ever go there and just go to a few of the graveyards around that farm, you would stumble over one little, tiny gravestone after another after another. I mean, infant mortality rates were through the roof. And it was actually bad luck to name your baby before it reached one year old. And Bathsheba Sherman was by some, I guess, accused of practicing witchcraft. She was apparently a very beautiful woman and the other women in town were threatened by her. It was back in the time when folklore and old wives tales and the accusation of being a witch could get you killed up in San Luis, which was just like an hour north of where we were living. And had it been a little bit different time, she could have paid with her life for being accused of that. But instead, it was just a vicious rumor that circulated that she had killed the baby for making a deal with the devil for eternal youth and beauty. We listen to all of that now and say, “Well, that’s just stupid. You know, that’s just superstitious nonsense. The woman would not be buried in the middle of hallowed ground in the Riverside Cemetery in Harrisville next to her husband and all of her children had there been any proof that she was a practicing witch.” I will spend the rest of my life defending her because even though I don’t know for certain if she had anything to do with the death of that child, I don’t think it’s fair to accuse someone of murder unless you have some evidence as proof. And there was no evidence back then. There was no DNA. There was nothing. And so, I just don’t think that she had anything to do with that.

I think that it was a very unfair condemnation of her. But unfortunately, the Warrens were asking my mother to be able to do an investigation of the house. My mother told her what she knew about the history of the house. After Lorraine came up with that name, my mother said, “Well, I’ve been doing some historical research on this property and some surrounding properties in the area.” And she showed Lorraine her notebook that was filled with stories and birth certificates and death certificates. On her second or third visit, Mrs. Warren asked for the notebook, and it was filled with descriptions of the spirits in the house. It was filled with drawings of the spirits that my mother had seen. And Mrs. Warren asked if she could borrow that thick notebook of absolutely invaluable information. And she wanted to make Xerox copies of it, so it tells you what time in history that was. My mother begrudgingly handed it over to her with the promise that she would get it back. But she never did return it. Mrs. Warren kept it. It was our understanding that when the movie The Conjuring was made that that notebook was sold as part of her case files. And it’s gone. We never ever saw it again. My mother asked for it back.

My mother felt that it was part of her legacy to her children. Mrs. Warren perceived it to be a haunted item and didn’t think that it belonged in the house. So, she told my mother she would return it, but then she never did and like 15 years later, she sold it. A number of things that we had found on the property went missing when they came one night with their team. It was the night of the séance that they foisted upon my mother, insisting that she was being oppressed and that she was right on the verge of possession and if they didn’t intervene on her behalf at that point that she would be lost. That was the most horrible night of my life. I was 15 when that happened. And I remember it like it just happened. It was absolutely traumatizing. I suffer PTSD from it. I swear to you I do. It was just a few minutes, but in those few minutes, I saw the dark side of existence and that is why I choose deliberately to live in the light. I will never let anything that evil touch me. I never will.

The Warrens only came maybe five times over the course of about a year and a half. And the last time that they came was after the séance. And when my father threw them out of the house that night along with their entourage, they left that house with my mother unconscious on the parlor floor. They came back to see if she had survived that night because when they left that house, they didn’t know if she was dead or alive. It was horrible. I don’t want to disparage them. They can’t defend themselves. Mrs. Warren, I think her heart was in the right place. I mean, she was a collector of objects. Their paranormal museum didn’t make itself. Every investigation she ever did, she had something from that investigation that went into their paranormal museum. And I know people personally who’ve been through it and have seen items that disappeared from our house the night of the séance that are under glass in that museum now.

BD: Do you know if that notebook was in their paranormal museum?

AP: No, it never was. Not that I know of. No, that was kept separately.

BD: What were your interactions with the Warrens like during the times that they were doing their investigation?

AP: Mrs. Warren didn’t really have anything much to do with us, with the children. She kind of turned us over to Ed, and he’s the one that interviewed us individually. My little sister, April, had a friend, a spirit friend, up in the chimney closet between the first and second bedroom. And she wouldn’t tell them about him. And he had identified himself to her as Oliver Richardson. But she wouldn’t tell Ed about him because she was afraid that the Warrens would make him go away and she loved him. And she felt very protective of him. And he was basically the same age as she was in life when he died. So, they had a very strong connection that she was not willing to jeopardize by telling them anything about him. But the rest of us just spilled our guts. It was kind of cathartic. It was a relief to be able to talk about the activity in that house with someone who believed us.

The night that Mrs. Warren originally came to the house, Mrs. Warren told my mother that I was in the room. I was a witness to this conversation. And she told my mother that the reason, even though she had known about our predicament for a number of weeks, she decided that she and her husband would not come out to the house until Halloween was because she said that’s when the veil has thinned. And I remember my mother looking at her and then kind of not laughing because it was certainly not a laughing matter, but kind of this incredulous grunt came out of her like, well, and then she just looked at her and she said, “Well then, I guess every day is Halloween at this house and there is no veil. I don’t know what you’re talking about, this veil. There’s no veil here. We share this with a lot of spirits.” One of the things that my mother resented about the film The Conjuring—I understand why they did what they did. I get it. But what they tried to do is juxtapose the devout Roman Catholic paranormal investigators, Ed and Lorraine Warren, against the godless heathen parent family. You know, like we were, I won’t say pagan because pagan is a religion also, but that we didn’t have any connection to the church. And my mother took great exception to that. She didn’t even watch the film until it had been out on DVD for more than a year.

I thought that she would be very upset about the way she was represented in the film. Some of it she thought was just so ridiculous that it was not anything that she would bother to take exception to. But the one thing that she was really offended by was that our portrayal was that of a family that had no faith. And nothing could have been further from the truth. My father was born and raised in a staunch Catholic tradition as the eldest of six boys. Church was an integral part of his childhood and his family’s life. He went to parochial school, and he served as an altar boy for years of his youth. And when he graduated from high school, he went into the Navy with the intention of serving the country and then going immediately into seminary to become a priest. That’s what my father’s life plan was. And in the interim, he met my mother and fell in love. And so, the priesthood thing was out the window. But my mother, who he met in Georgia, was a Southern Baptist. And she had to convert to Catholicism in order to marry him. All of us were baptized and all of us made our first communion and all of us were raised in the Roman Catholic Church.

It was the second year, the second Easter that we were at the farm. April was seven years old, and we went to Easter Mass, and we filled our own pew. There were so many of us. And at the very end of Mass, the priest said, “and the father and the son and the Holy Ghost.” And April turned and just with her big blue eyes just looked up at my mother and she said in her big girl, outdoor voice, “See, Mom, God has ghosts just like we do.” And every single head in that church turned and looked at our family. And as we got up to leave, the priest followed us out and he came up to my father and he said, “Mr. Perron, I would appreciate it if you would take your family and worship elsewhere.” My father was so angry and so hurt that he felt abandoned by the religion that he had invested himself into his whole life. I have rarely seen my father cry and he cried on the way home that day. As we were all getting out of our big Pontiac Bonneville car, which we called the Catholic Mobile because it had room for seven plus luggage and the family dog, my mother said, “Girls, if you want to know God, go to the woods. Go to the woods.” We never ever went back to church again. Ever. Our family has never been together in a church ever since then.

BD: That’s awful for a priest to react that way to a child.

AP: The priest was afraid. He was afraid that he had that weird family from the old, haunted house up on Round Top Road in St. Patrick’s Parish. And that others might not come back to the parish if we were there. I was already in catechism classes to make my confirmation and, you know, all my friends were Catholics. Everybody went to St. Patrick’s. I would just go and kind of sit in the back of the class and all my peers were there who were getting ready to make their final confirmation into the church. It was the nuns who were teaching us. But one night, the priest was there, and he recognized me. And sure as hell, not a week later, my parents received a letter from the Bishop, who was the head of the diocese of Providence, informing my parents that I was not welcome in confirmation classes because I asked too many questions. That was it. There was something about living in that house that made you more faithful. And I found out very early on that when all hell was breaking loose in that house and there was a lot of negative energy swirling in the house, or I felt threatened or any of my sisters felt threatened, all you ever had to do was say, “Oh God, help me. “And it stopped instantly. Good conquers evil and love conquers fear. And hatred is not the opposite of love. Fear is the opposite of love and hatred is born of fear.

I believe in my heart that the Warrens had the best of intentions. 40 years later, when I saw Mrs. Warren again out in California when she and I had been invited to preview The Conjuring before it was released, she recognized me immediately and came and wrapped her arms around me. During those three days that we spent in California together, she told me that she and Ed were in over their heads the moment they crossed the threshold of that house. They just didn’t know it. She admitted terrible mistakes were made. They didn’t mean to stir up activity, but she was a bona fide clairvoyant. She had great abilities, and she didn’t always use them to their greatest good. And I think that that was because of her fascination but also her reverence and respect for spirits. She knew that spirits were real, but unfortunately, because of her sensing Bathsheba in the house, who was really only a neighbor—Her sense of that spirit’s presence is what changed everything. Because not only did she have a sense of her presence and we didn’t find out until five decades later that her husband, Judson Sherman, died on that property. We still don’t know how he died. One of my historian friends dug up that he died at the Arnold state. We don’t know how, but that would explain why her presence would be there. You know, spirits are free to come and go as they please.

They’re not locked into an earthbound, specific location. There are differences of opinion even within our own family about how free the spirits are. My sister Cindy will still argue with me about it. She believes that they’re attached to the farm because she said that when we moved, they loved us so much that if they could have come with us, they would have. My response to her is that the spirit that was standing behind Nancy on the front porch of that house the day the whole rest of the family left for Georgia was the spirit that was standing behind my sister Cindy when we arrived at the new house in Georgia. Same exact woman; same entity standing right behind her. And Cindy’s like, “No, no, it must have been somebody else. It must have been one of my guides because the spirits are stuck there. They’re trapped there. And I’m like, “No, they’re not, babe.”

‘The Conjuring’ Movie House – Photo Credit: J. Patrick Swope

BD: How much of what we see in The Conjuring really happened?

AP: There are so many discrepancies between The Conjuring and the real story that is documented in House of Darkness House of Light, the trilogy of books that I wrote that they are unrecognizable except for the names. Everybody that was associated with the film read my books, including the actors, except for maybe the youngest children couldn’t read them. But everybody, all the adults for sure, read the books and said, “Oh, hell no, we can’t tell this story,” because they were about to invest somewhere between $25 and $30 million into making this film. And it was based predominantly on the case files of Ed and Lorraine Warren. It says right on the movie trailer, case files of Ed and Lorraine. But I gave them permission to use anything that was in my books that was the actual story, the authentic telling of our family memoir. And they wouldn’t. The screenwriters, Chad and Carey Hayes, twin brothers, lovely men, wanted desperately to include elements of the true story and they wrote some of the stories into the screenplay. And every single time the suits at New Line Cinema and Warner Brothers sent the script back and said, “Take that out, redact it. We’re not going to run people out of the theater. We’re not going to make a movie that nobody will stay to watch to the end because they are terrified.” So, The Conjuring is a very toned-down version of events.

BD: Why didn’t they want to use it?

AP: They thought it was too scary; it was too real; it was too raw. It was, I mean, people who read my trilogy of books are changed. They are never the same again. When they come up for air after that deep dive, they think about everything differently. Nothing is ever the same. A lot of my readers over the years have deemed it interactive literature. They feel like by the time they’re done reading volume three, that they lived there with us, that they grew up with us, that they know every member of my family intimately well, and that they had the same experiences that we did. There’s something about this story that unlocks a person’s third eye and opens them to the netherworld in a way that nothing else ever has or ever could. Actually, the ability to expand human consciousness is not the most important part of the trilogy. House of Darkness House of Light got its title from my mother when I was about 300 pages into the first book. And she asked me what I was going to title the trilogy, and I told her I didn’t know. And she stood next to me at her old cherry desk right here in the room in which I’m sitting speaking with you right now. I wrote those books in this house. And she just looked at me and she said, “House of Darkness House of Light,” it was both. No comma, it was both. And so, there is no comma. It’s House of Darkness House of Light as one thing because my mother believes the same way that I do; that everything is energy, and everything is consciousness, and everything is one thing.

There is no delineation between natural and supernatural, between normal and paranormal. At least there isn’t for us. This is just how our lives are now. That you cannot experience what we did immersed in that environment for a decade and be unchanged by it. And I think the greatest value in me finding the courage to finally tell our story more than, I didn’t even start writing it until more than three decades after we had left. But I finally got to an age and a place in my own mind where I didn’t care how people were going to react to it anymore. I knew that we would be scrutinized. I knew that we would be belittled. I knew that there would be mean-spirited people out there that would attack our family. And instead, we were embraced by the paranormal community worldwide.

I would not be one of the very best-selling authors in this genre worldwide had it not been for The Conjuring. So, I don’t hold any grudges. The power of a well-made feature film and the images that are placed in people’s minds is what causes them to dig deeper. And based on a true story, well where’s the true story? Who wrote the true story? All they have to do is Google the name Perron and up come the books. They’ve been read all over the world. Hundreds of thousands of copies have been sold. And they’re selling better now than they did after the film came out. So, the story is getting around. And I think that the great value of the story is not the expansion of human consciousness. It is liberating people to tell their own story. Because so many people have been touched by spirits and they’re afraid to share it. They’re afraid to speak out. They’re afraid to be criticized and to be treated as somehow less than. Or I’ve often been asked, “Was there ever a time that you questioned your own sanity?” Oh, hell yes. And that is true of every member of my family. We saw things in that house that there’s no plausible explanation other than spirits are real.

We’re still learning things about that house and about the spirits who quote unquote live there, who dwell there. And I love them. I even love the cranky ones. I do because to me it doesn’t even matter who they were, that they still are is a freaking miracle. That is magical. That is cosmic forces beyond our comprehension. One of my famous quotations is very simple, but it’s very true—To be touched by a spirit is not a curse, but a blessing. It is that rare glimpse into the realm from which we come and will all inevitably return. And I end it with, be not afraid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.