Editorials

Happy 20th Anniversary to ‘Copycat!’

October 27th brings us the 20th anniversary of the oft-forgotten thriller* Copycat, starring Sigourney Weaver, Holly Hunter, Dermot Mulroney and Harry Connick, Jr. Released in 1995 at the tail-end of copycats (sorry) of The Silence of the Lambs, Copycat tends to slip by in discussions of great serial killer thrillers, since Scream would come out a year later and overshadow most 90s slashers that came before it. Not that Copycat is necessarily a slasher, but you’re more likely to find someone who has never heard of Copycat over someone who has never heard of Scream of The Silence of the Lambs, and that’s just not right.

*Before you cry “But Copycat isn’t a horror film,” please allow me to direct you to Jonathan’s post right here. If The Silence of the Lambs can be considered horror, so can Copycat.

***SPOILERS of a 20-year-old film to follow***

In Copycat, an attack by serial killer Daryll Lee Cullum (Harry Connick, Jr.) renders renowned criminal psychologist Helen Hudson (Sigourney Weaver) an agoraphobic. Thirteen months after the attack, a different serial killer begins to copycat some of the most notorious serial killers of the century. With the help of Inspector M.J. Monahan (Holly Hunter) and her partner Reuben Goetz (Dermot Mulroney), they work together to track the copycat before he can kill more people.

What makes Copycat such a special film is that unlike so many other films in the genre, it avoids gender stereotypes. The women are the stars of the show and they are capable of taking care of themselves. Even Weaver’s character, who is relegated to her apartment for 90% of the film, is portrayed as a strong female, despite her handicap.

Copycat’s parallels with The Silence of the Lambs are apparent. In Copycat, Monahan but use the help of an incarcerated expert on criminals and psychopaths (Weaver) to help her solve a crime, just as Clarice Starling had to utilize the help of Hannibal Lecter. Copycat’s twist on this plot is to have the incarcerated intellectual be female and not a criminal. Monahan is also a seasoned police inspector compared to the rookie Clarice Starling. To my knowledge (and I could be wrong), this is the first film to feature two women law enforcement officers working together to take down the villain. Dermot Mulroney’s Goetz is the sidekick and rookie in this film, and he gets killed at the end of the second act by a random criminal in the police station.

The Silence of the Lambs isn’t the only film that influenced Copycat. Wait Until Dark, the 1967 Audrey Hepburn thriller in which she is confined to her apartment because of her blindness. Helen’s agoraphobia directly parallels Hepburn’s character’s vision impairment.

Copycat was a type of feminist movie that no one had ever seen before, which makes it unfathomable that it isn’t name-dropped in film discussions more often. Its influence can be seen even in films like The Heat. Hell, the film even has a gay character whose sexual orientationis barely mentioned, which isn’t even something that’s common in films that are released today.

While the feminist ideals and the chemistry between the two leads is a major selling point of Copycat, the film has so much more going for it. Directed by John Amiel (who would go on to direct critical darlings Entrapment and The Core), Copycat features stella performances from everyone in the cast. Connick, Jr. has never been creepier, Mulroney is great as the junior detective and even William McNamara plays a great villain you love to hate.

Part of the fun of Copycat is the crime scenes. Watching the film plays like a “Greatest Hits” edition of America’s most notorious serial killers. From The Boston Strangler to Son of Sam to Ted Bundy, Copycat hits all the major players. While it is very much a cop movie, the film features the psychological elements much more prominently, making it a more compelling film.

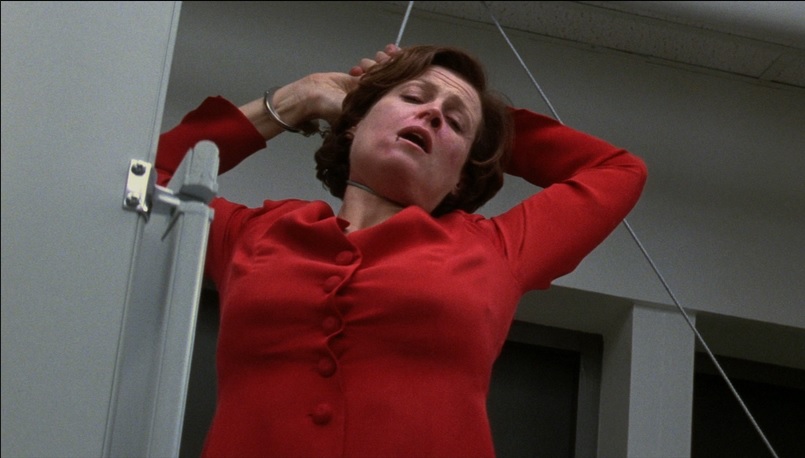

There are disturbing moments aplenty in the film (though nothing particularly gory), the primary one being the opening sequence of Connick’s attack on Weaver, but there are severed fingers left in books, ants set loose in a bed, a really creepy animated email video and the climactic showdown between Helen and the titular copycat. Twists and turns feature prominently in Copycat, but the fun comes from watching Helen and M.J. piece together the clues to determine the killer’s pattern (the reveal is particularly clever).

Of course, Copycat is not a perfect film. Despite the aforementioned twists and turns, the overall narrative arc is pretty predictable (Helen must eventually face her agoraphobia head-on) and the twist in the final scene, while creepy, isn’t wholly necessary (and is a tease for a sequel that never came to fruition).

That being said, Copycat is still one of the more underrated thrillers of the 90s that should find its way back into popular culture. It did moderately well at the box office, making $32 million on a $20 million budget, so clearly some people have seen it. Give it a re-watch (or watch it for the first time) this week to celebrate its 20th anniversary!

Books

‘See No Evil’ – WWE’s First Horror Movie Was This 2006 Slasher Starring Kane

With there being an overlap between wrestling fans and horror fans, it only made sense for WWE Studios to produce See No Evil. And much like The Rock’s Walking Tall and John Cena’s The Marine, this 2006 slasher was designed to jumpstart a popular wrestler’s crossover career; superstar Glenn “Kane” Jacobs stepped out of the ring and into a run-down hotel packed with easy prey. Director Gregory Dark and writer Dan Madigan delivered what the WWE had hoped to be the beginning of “a villain franchise in the vein of Jason, Freddy and Pinhead.” In hindsight, See No Evil and its unpunctual sequel failed to live up to expectations. Regardless of Jacob Goodnight’s inability to reach the heights of horror’s greatest icons, his films are not without their simple slasher pleasures.

See No Evil (previously titled Goodnight and Eye Scream Man) was a last gasp for a dying trend. After all, the Hollywood resurgence of big-screen slashers was on the decline by the mid-2000s. Even so, that first Jacob Goodnight offering is well aware of its genre surroundings: the squalid setting channels the many torturous playgrounds found in the Saw series and other adjacent splatter pics. Also, Gregory Dark’s first major feature — after mainly delivering erotic thrillers and music videos — borrows the mustardy, filthy and sweaty appearance of Platinum Dunes’ then-current horror output. So, visually speaking, See No Evil fits in quite well with its contemporaries.

Despite its mere setup — young offenders are picked off one by one as they clean up an old hotel — See No Evil is more ambitious than anticipated. Jacob Goodnight is, more or less, another unstoppable killing machine whose traumatic childhood drives him to torment and murder, but there is a process to his mayhem. In a sense, a purpose. Every new number in Goodnight’s body count is part of a survival ritual with no end in sight. A prior and poorly mended cranial injury, courtesy of Steven Vidler’s character, also influences the antagonist’s brutal streak. As with a lot of other films where a killer’s crimes are religious in nature, Goodnight is viscerally concerned with the act of sin and its meaning. And that signature of plucking out victims’ eyes is his way of protecting his soul.

Image: The cast of See No Evil enters the Blackwell Hotel.

Survival is on the mind of just about every character in See No Evil, even before they are thrown into a life-or-death situation. Goodnight is processing his inhumane upbringing in the only way he can, whereas many of his latest victims have committed various crimes in order to get by in life. The details of these offenses, ranging from petty to severe, can be found in the film’s novelization. This more thorough media tie-in, also penned by Madigan, clarified the rap sheets of Christine (Christina Vidal), Kira (Samantha Noble), Michael (Luke Pegler) and their fellow delinquents. Readers are presented a grim history for most everyone, including Vidler’s character, Officer Frank Williams, who lost both an arm and a partner during his first encounter with the God’s Hand Killer all those years ago. The younger cast is most concerned with their immediate wellbeing, but Williams struggles to make peace with past regrets and mistakes.

While the first See No Evil film makes a beeline for its ending, the literary counterpart takes time to flesh out the main characters and expound on scenes (crucial or otherwise). The task requires nearly a third of the book before the inmates and their supervisors even reach the Blackwell Hotel. Yet once they are inside the death trap, the author continues to profile the fodder. Foremost is Christine and Kira’s lock-up romance born out of loyalty and a mutual desire for security against their enemies behind bars. And unlike in the film, their sapphic relationship is confirmed. Meanwhile, Michael’s misogyny and bigotry are unmistakable in the novelization; his racial tension with the story’s one Black character, Tye (Michael J. Pagan), was omitted from the film along with the repeated sexual exploitation of Kira. These written depictions make their on-screen parallels appear relatively upright. That being said, by making certain characters so prickly and repulsive in the novelization, their rare heroic moments have more of an impact.

Madigan’s book offers greater insight into Goodnight’s disturbed mind and harrowing early years. As a boy, his mother regularly doled out barbaric punishments, including pouring boiling water onto his “dangling bits” if he ever “sinned.” The routine maltreatment in which Goodnight endured makes him somewhat sympathetic in the novelization. Also missing from the film is an entire character: a back-alley doctor named Miles Bennell. It was he who patched up Goodnight after Williams’ desperate but well-aimed bullet made contact in the story’s introduction. Over time, this drunkard’s sloppy surgery led to the purulent, maggot-infested head wound that, undoubtedly, impaired the hulking villain’s cognitive functions and fueled his violent delusions.

Image: Dan Madigan’s novelization for See No Evil.

An additional and underlying evil in the novelization, the Blackwell’s original owner, is revealed through random flashbacks. The author described the hotel’s namesake, Langley Blackwell, as a deviant who took sick pleasure in defiling others (personally or vicariously). His vile deeds left a dark stain on the Blackwell, which makes it a perfect home for someone like Jacob Goodnight. This notion is not so apparent in the film, and the tie-in adaptation says it in a roundabout way, but the building is haunted by its past. While literal ghosts do not roam these corridors, Blackwell’s lingering depravity courses through every square inch of this ill-reputed establishment and influences those who stay too long.

The selling point of See No Evil back then was undeniably Kane. However, fans might have been disappointed to see the wrestler in a lurking and taciturn role. The focus on unpleasant, paper-thin “teenagers” probably did not help opinions, either. Nevertheless, the first film is a watchable and, at times, well-made straggler found in the first slasher revival’s death throes. A modest budget made the decent production values possible, and the director’s history with music videos allowed the film a shred of style. For meatier characterization and a harder demonstration of the story’s dog-eat-dog theme, though, the novelization is worth seeking out.

Jen and Sylvia Soska, collectively The Soska Sisters, were put in charge of 2014’s See No Evil 2. This direct continuation arrived just in time for Halloween, which is fitting considering its obvious inspiration. In place of the nearly deserted hospital in Halloween II is an unlucky morgue receiving all the bodies from the Blackwell massacre. Familiar face Danielle Harris played the ostensible final girl, a coroner whose surprise birthday party is crashed by the resurrected God’s Hand Killer. In an effort to deliver uncomplicated thrills, the Soskas toned down the previous film’s heavy mythos and religious trauma, as well as threw in characters worth rooting for. This sequel, while more straightforward than innovative, pulls no punches and even goes out on a dark note.

The chances of seeing another See No Evil with Kane attached are low, especially now with Glenn Jacobs focusing on a political career. Yet there is no telling if Jacob Goodnight is actually gone, or if he is just playing dead.

Image: Katharine Isabelle and Lee Majdouba’s characters don’t notice Kane’s Jacob Goodnight character is behind them in See No Evil 2.

You must be logged in to post a comment.