‘Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III’ Still Has Teeth 28 Years Later

-

“Pretty Little Liars: Summer School” Official Trailer Assembles the Final Girls and Starts Slashing

-

‘Trap’ – Official Trailer Previews a Wild New Horror Experience from M. Night Shyamalan

-

‘Transformers One’ Trailer – Chris Hemsworth Voices Optimus Prime in Brand New Animated Movie

-

‘Nightwatch: Demons Are Forever’ Trailer Teases the Return of Familiar Faces and an Unsettling New Killer

In 1989, just three short years after Tobe Hooper drove the serrated end of a Stihl through Bubba Sawyer’s belly during the climax of the darkly comedic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 – ostensibly ending both the franchise and Hooper’s career – New Line Cinema swooped in, bought the rights to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and set out to make the lumbering Leatherface their newest mascot. The ’80s had been good to New Line, thanks mainly in part to their resident maniac Freddy Krueger; he’d built their house – now Leatherface was going to build their toolshed.

To help hone their vision, New Line hired author David J. Schow – known for his “splatterpunk” work, a term he coined himself – to pen the script. Schow, no stranger to blood and guts, delivered on the viscera – but he also brought back the unhinged, dangerous vibe from the original film. His script was filled with the colorful characters, dire situations, and bone-shattering violence Tobe Hooper had established with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

After approaching a few potential suitors to direct the film (including Tom Savini and Peter Jackson, both of whom turned it down), New Line settled on 26-year-old Jeff Burr, a relatively new face who’d just directed the moderately-received Stepfather II. His respect for the franchise was obvious from the start as his initial suggestions to New Line made clear: he’d direct the film, but he wanted to shoot in Texas on 16 mm, just like the original, and he wanted Gunnar Hansen back as Leatherface. New Line’s response was to fire Burr, just a week into production. New Line didn’t want creative; they wanted familiar. With Leatherface, they wanted a guaranteed franchise star. Alas, with no one willing to take on the duties of what was shaping up to be a tumultuous shoot, New Line had no choice but to rehire Burr.

From the beginning, the production was fraught with setbacks – something that would haunt the shoot until the very end. Crew members dropped out, wildfires destroyed locations they had planned to use, and after the movie wrapped the MPAA slapped it with an X rating – a death knell for horror films at the time (TCM III was the last film to be given an X-rating). Even after trimming almost 5 minutes of footage, test audiences encouraged the studio to completely reshoot the ending – something Burr himself didn’t even discover until he watched the final version in a theater.

Because of the heavy editing and reshoots, the film – which was slated for a November release – was bumped to January, known as a “dump month”. One of the worst times of year for a film to open, it’s where films usually go to die. Upon release, critics tore the film to shreds. Many of the newspaper reviews were so disdainful, the critics didn’t even bother to get the plotline or character names correct in the write-up.

In the end, despite all the strikes against it, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III managed to scrounge up a $3M profit. Still, it wasn’t enough to convince the fickle New Line (namely CEO Bob Shaye) to continue making more Leatherface sequels. They wouldn’t be involved in another Massacre film until almost 15 years later, when they released the remake.

They didn’t want creative; they wanted familiar.

Regardless of its initial reception, it’s now almost 30 years later, and fans of the film are still remembering it fondly and clamoring for more. Warts and all, TCM III struck a chord with the burgeoning gorehounds at the time as well as the older fans of the original. Despite its micro budget, TCM III does an incredible job with its production and design. The production was lucky to snag the KNB EFX Group (Nicotero and Berger, back when they were partners with Kurtzman) on what was one of their first projects as a group. They provided every severed arm, filleted face, and chainsawed head, much to the chagrin of the MPAA – but to the delight of fans.

And then there’s the lighting: the night lighting used throughout the film is gorgeous and used to great effect, creating not only ambiance but also setting a dreadful mood. It’s some of the best night-lighting in a horror film this side of Halloween. While our hulking killer stalks his human prey through the moonlit Texas woods, their frightened expressions are cast in a ghostly navy blue hue, as if they’re already dead and don’t even know it. And when the malicious Tink shows up in his tow truck to do some post-accident clean-up, the scene is lit solely by car headlights and flickering red flares, making Tink look like the Devil himself. At times, the lighting choices almost feel Michael Mann-esque: earlier in the film, as our victims speed off from the dusty and desolate Last Chance Gas Station aimlessly into the night, the camera cranes above the blackened landscape, the only light visible being the sickly neon green glow from a dingy fluorescent light above one of the pumps and a dying purple sunset in the distance. Altogether, its color palette makes it feel like a hillbilly giallo film.

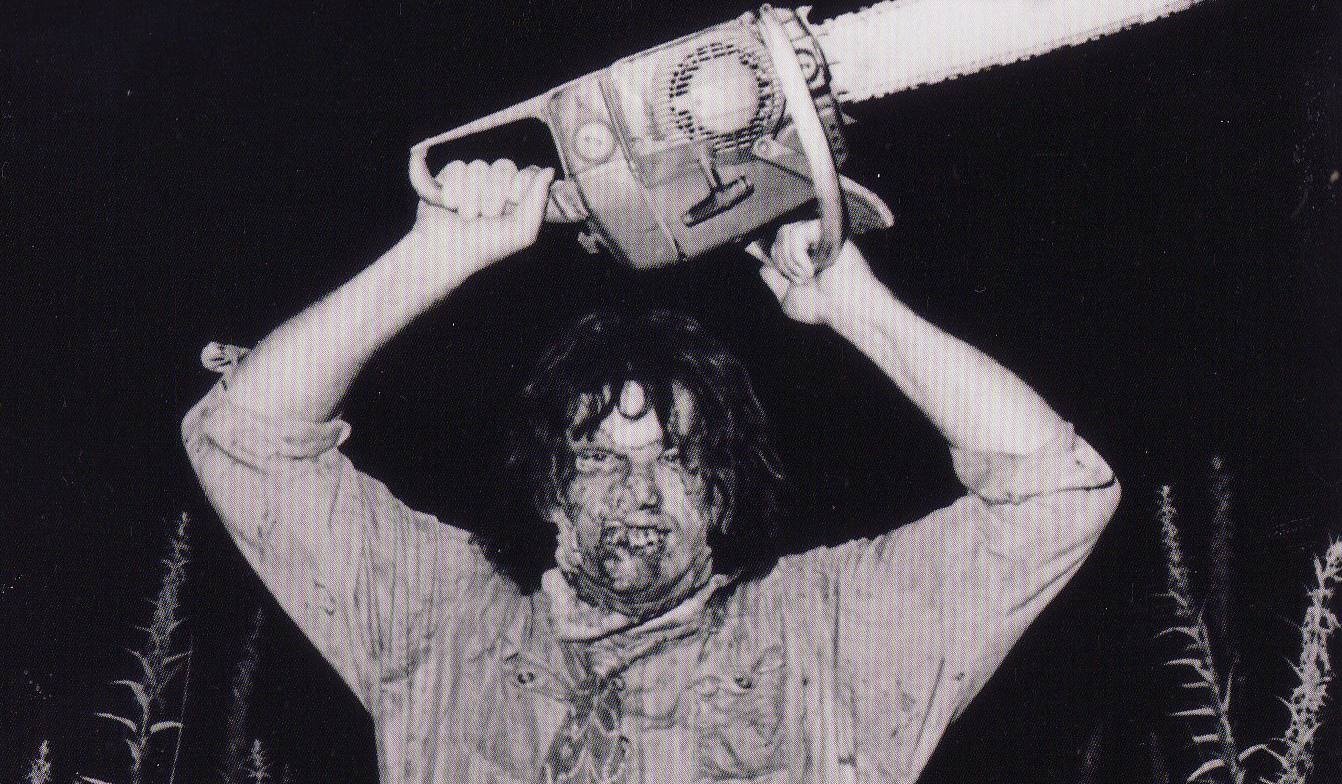

The most important part of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III is that it made Leatherface scary again. When the world was introduced to Leatherface in the original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, he was a destructive toddler; a whirlwind of petulance, frustration, and unpredictability exacerbated by his abusive, domineering brothers. He resolved every problem by destroying it, which is innately scary. In the sequel, however, he became sort of a bumbling, horny tween, dopey and love-struck with the unobtainable and leggy Stretch. He’d become a puppy. But by TCM III, he’d entered his teenage phase, instilling again in him the short-temperedness he hadn’t experienced since the first film. He’d become self-aware, self-conscious, and aloof. He was no longer taking orders from his brothers; he was sticking their hands in the oven to retrieve his heavy metal cassette tape. He was a force once again. He was terrifying.

Burr’s TCM III is at once a love letter to the original film and an attempt to reclaim what made the original such an indelible part of horror history. And it’s evident in the final product – or, what’s left of it. It’s all water under the bridge now, but it’s hard not to try to imagine what Burr could’ve done with the franchise had New Line let him make his vision.

“So,” asks the disarming Tex, as he drives a spike through the hand of our heroine, pinning her to the chair in which she’s strapped, “how you like Texas?”

We like it just fine.

Editorials

‘A Haunted House’ and the Death of the Horror Spoof Movie

Due to a complex series of anthropological mishaps, the Wayans Brothers are a huge deal in Brazil. Around these parts, White Chicks is considered a national treasure by a lot of people, so it stands to reason that Brazilian audiences would continue to accompany the Wayans’ comedic output long after North America had stopped taking them seriously as comedic titans.

This is the only reason why I originally watched Michael Tiddes and Marlon Wayans’ 2013 horror spoof A Haunted House – appropriately known as “Paranormal Inactivity” in South America – despite having abandoned this kind of movie shortly after the excellent Scary Movie 3. However, to my complete and utter amazement, I found myself mostly enjoying this unhinged parody of Found Footage films almost as much as the iconic spoofs that spear-headed the genre during the 2000s. And with Paramount having recently announced a reboot of the Scary Movie franchise, I think this is the perfect time to revisit the divisive humor of A Haunted House and maybe figure out why this kind of film hasn’t been popular in a long time.

Before we had memes and internet personalities to make fun of movie tropes for free on the internet, parody movies had been entertaining audiences with meta-humor since the very dawn of cinema. And since the genre attracted large audiences without the need for a serious budget, it made sense for studios to encourage parodies of their own productions – which is precisely what happened with Miramax when they commissioned a parody of the Scream franchise, the original Scary Movie.

The unprecedented success of the spoof (especially overseas) led to a series of sequels, spin-offs and rip-offs that came along throughout the 2000s. While some of these were still quite funny (I have a soft spot for 2008’s Superhero Movie), they ended up flooding the market much like the Guitar Hero games that plagued video game stores during that same timeframe.

You could really confuse someone by editing this scene into Paranormal Activity.

Of course, that didn’t stop Tiddes and Marlon Wayans from wanting to make another spoof meant to lampoon a sub-genre that had been mostly overlooked by the Scary Movie series – namely the second wave of Found Footage films inspired by Paranormal Activity. Wayans actually had an easier time than usual funding the picture due to the project’s Found Footage presentation, with the format allowing for a lower budget without compromising box office appeal.

In the finished film, we’re presented with supposedly real footage recovered from the home of Malcom Johnson (Wayans). The recordings themselves depict a series of unexplainable events that begin to plague his home when Kisha Davis (Essence Atkins) decides to move in, with the couple slowly realizing that the difficulties of a shared life are no match for demonic shenanigans.

In practice, this means that viewers are subjected to a series of familiar scares subverted by wacky hijinks, with the flick featuring everything from a humorous recreation of the iconic fan-camera from Paranormal Activity 3 to bizarre dance numbers replacing Katy’s late-night trances from Oren Peli’s original movie.

Your enjoyment of these antics will obviously depend on how accepting you are of Wayans’ patented brand of crass comedy. From advanced potty humor to some exaggerated racial commentary – including a clever moment where Malcom actually attempts to move out of the titular haunted house because he’s not white enough to deal with the haunting – it’s not all that surprising that the flick wound up with a 10% rating on Rotten Tomatoes despite making a killing at the box office.

However, while this isn’t my preferred kind of humor, I think the inherent limitations of Found Footage ended up curtailing the usual excesses present in this kind of parody, with the filmmakers being forced to focus on character-based comedy and a smaller scale story. This is why I mostly appreciate the love-hate rapport between Kisha and Malcom even if it wouldn’t translate to a healthy relationship in real life.

Of course, the jokes themselves can also be pretty entertaining on their own, with cartoony gags like the ghost getting high with the protagonists (complete with smoke-filled invisible lungs) and a series of silly The Exorcist homages towards the end of the movie. The major issue here is that these legitimately funny and genre-specific jokes are often accompanied by repetitive attempts at low-brow humor that you could find in any other cheap comedy.

Not a good idea.

Not only are some of these painfully drawn out “jokes” incredibly unfunny, but they can also be remarkably offensive in some cases. There are some pretty insensitive allusions to sexual assault here, as well as a collection of secondary characters defined by negative racial stereotypes (even though I chuckled heartily when the Latina maid was revealed to have been faking her poor English the entire time).

Cinephiles often claim that increasingly sloppy writing led to audiences giving up on spoof movies, but the fact is that many of the more beloved examples of the genre contain some of the same issues as later films like A Haunted House – it’s just that we as an audience have (mostly) grown up and are now demanding more from our comedy. However, this isn’t the case everywhere, as – much like the Elves from Lord of the Rings – spoof movies never really died, they simply diminished.

A Haunted House made so much money that they immediately started working on a second one that released the following year (to even worse reviews), and the same team would later collaborate once again on yet another spoof, 50 Shades of Black. This kind of film clearly still exists and still makes a lot of money (especially here in Brazil), they just don’t have the same cultural impact that they used to in a pre-social-media-humor world.

At the end of the day, A Haunted House is no comedic masterpiece, failing to live up to the laugh-out-loud thrills of films like Scary Movie 3, but it’s also not the trainwreck that most critics made it out to be back in 2013. Comedy is extremely subjective, and while the raunchy humor behind this flick definitely isn’t for everyone, I still think that this satirical romp is mostly harmless fun that might entertain Found Footage fans that don’t take themselves too seriously.

You must be logged in to post a comment.