Editorials

[Butcher Block] The Uncomfortable Realism of ‘Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer’

Butcher Block is a weekly series celebrating horror’s most extreme films and the minds behind them. Dedicated to graphic gore and splatter, each week will explore the dark, the disturbed, and the depraved in horror, and the blood and guts involved. For the films that use special effects of gore as an art form, and the fans that revel in the carnage, this series is for you.

Movies have a long-standing relationship with serial killers, from larger-than-life fictional personalities like Patrick Bateman and Hannibal Lecter to true-crime enigmatic killers like Charles Manson and Ted Bundy; it’s as though there’s an inherent need to delve into the pathology behind these twisted minds in film. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer exists far removed from the rest; based on real-life serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, this horror film isn’t interested in the whys of its killer. Instead, it’s a voyeuristic window into his life, one so uncomfortable that the film sent the MPAA into a tizzy and wound up on the shelf for years until finally getting a release.

Co-writer/director John McNaughton’s feature debut, Henry doesn’t really have a story in the traditional sense. It opens to a shocking frame of a discarded dead woman, completely naked and covered in blood, before cutting to Henry (Michael Rooker), a seemingly normal man going through a mundane daily routine. As he quietly eats his breakfast before driving on through town, the film continues to juxtapose these ordinary moments with brutal shots of the dead bodies that Henry is leaving in his wake. It’s a chilling introduction to the casual, impulsive nature of Henry. This matter-of-fact style of slaying, combined with McNaughton’s choice to film in 16mm, gives Henry an overall gritty feel that seeks to drive home that the world’s scariest monsters have no motive behind their actions.

Henry shares an apartment with his former jail mate Otis (Tom Towles), who just picked up his younger sister Becky (Tracy Arnold) from the airport to stay with him for a while. Becky is the closest thing the film has to an audience proxy, a vulnerable young woman with a long history of sexual abuse who’s currently fleeing an abusive relationship. It’s through her that we learn a little more about Henry’s past, and it’s through her that we’re given just a smidgen of hope that there’s some kind of logic to Henry’s homicides. When Becky pries about Henry’s murder of his own mother, he can’t even get the details right. It’s a major red flag that hints at how many murders he’s committed, but also how very insignificant the act of murdering is to him. Becky’s too broken to notice; she instead relays her own traumatic past.

Once Otis embarks on a killing spree with Henry, McNaughton continues to ratchet up the tension, dread, and unease the more the pair gleefully approach their ruthless deeds with reckless abandon. It culminates in one harrowing doozy of a finale, and McNaughton brilliantly brings things full circle by having the film’s final victim unwittingly admire the guitar that belonged to one of Henry’s earliest victims, a hitchhiker.

The MPAA famously said that no number of edits would pass Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer with an R-rating. It’s a revealing statement considering how very little gore there is throughout the film, save for a couple of effective death sequences and cutaways to the bloody aftermath. When the film finally saw release a few years after its premiere at the Chicago International Film Festival, unrated no less, the reception was polarizing.

McNaughton delivered an unflinching portrayal of what a serial killer really looked like, saturated in realism and completely devoid of the entertainment value that usually sugarcoats the most depraved aspects of humanity. For some, being put into the voyeuristic role of watching Henry commit his heinous acts in all its ugliness was too much to handle. Brilliant direction and an uncanny performance by Rooker make Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer one of the most distressing, terrifying horror films of all time.

Sometimes it’s not gore that disturbs, but uncomfortable truths.

Editorials

‘Malevolence’: The Overlooked Mid-2000s Love Letter to John Carpenter’s ‘Halloween’

Written and Directed by Stevan Mena on a budget of around $200,000, Malevolence was only released in ten theaters after it was purchased by Anchor Bay and released direct-to-DVD like so many other indie horrors. This one has many of the same pratfalls as its bargain bin brethren, which have probably helped to keep it hidden all these years. But it also has some unforgettable moments that will make horror fans (especially fans of the original Halloween) smile and point at the TV like Leonardo DiCaprio in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Malevolence is the story of a silent and masked killer told through the lens of a group of bank robbers hiding out after a score. The bank robbery is only experienced audibly from the outside of the bank, but whether the film has the budgetary means to handle this portion well or not, the idea of mixing a bank robbery tale into a masked slasher movie is a strong one.

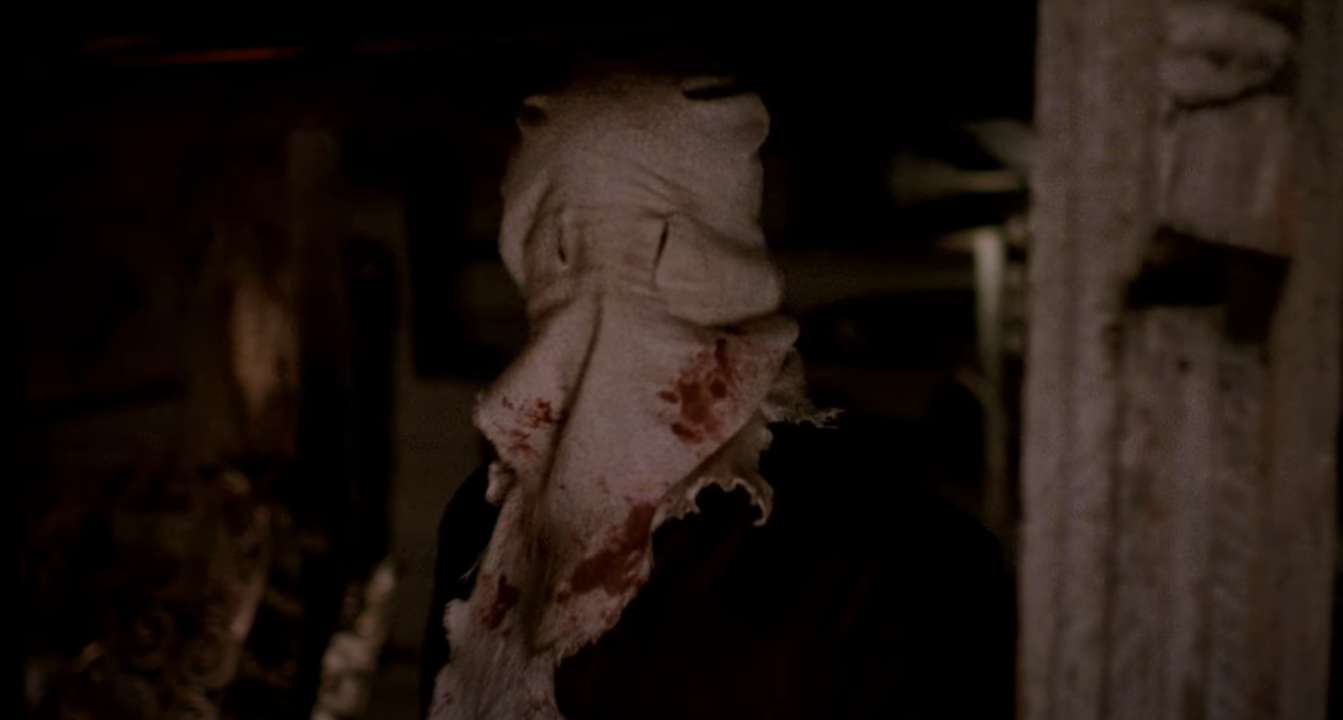

Of course, the bank robbery goes wrong and the crew is split up. Once the table is fully set, we have three bank robbers, an innocent mom and her young daughter as hostages, and a masked man lurking in the shadows who looks like a mix between baghead Jason from Friday the 13th Part 2 and the killer from The Town That Dreaded Sundown. Let the slashing begin.

Many films have tried to recreate the aesthetic notes of John Carpenter’s 1978 classic Halloween, and at its best Malevolence is the equivalent of a shockingly good cover song.

Though the acting and script are at times lacking, the direction, score, and cinematography come together for little moments of old-school slasher goodness that will send tingles up your spine. It’s no Halloween, to be clear, but it does Halloween reasonably proud. The nighttime shots come lit with the same blue lighting and the musical notes of the score pop off at such specific moments, fans might find themselves laughing out loud at the absurdity of how hard the homages hit. When the killer jumps into frame, accompanied by the aforementioned musical notes, he does so sharply and with the same slow intensity as Michael Myers. Other films in the subgenre (and even a few in the Halloween franchise) will tell you this isn’t an easy thing to duplicate.

The production and costume designs of Malevolence hint at love letters to other classic horror films as well. The country location not only provides for an opening Halloween IV fans will appreciate but the abandoned meat plant and the furnishings inside make for some great callbacks to 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. All of this is buoyed and accentuated by cinematography that you rarely see in today’s low-budget films. The film is shot on 35mm film by A&E documentary filmmaker Tsuyoshi Kimono, who gives Malevolence an old-school, grainy, 1970s aesthetic that feels completely natural and not like a cheap gimmick.

Malevolence is a movie that no doubt has some glaring imperfections but it is also a movie that is peppered with moments of potential. There’s a reason they made a follow-up prequel titled Malevolence 2: Bereavement years later (and another after that) that starred both Michael Biehn and Alexandra Daddario! That film tells the origin story of our baghead, Martin Bristol. Something the first film touches on a little bit, at least enough to give you the gist of what happened here. Long story short, a six-year-old boy was kidnapped by a serial killer and for years forced to watch him hunt, torture, and kill his victims. Which brings me to another fascinating aspect of Malevolence. The ending. SPOILER WARNING.

After the mother and child are saved from the killer, our slasher is gone, his bloody mask left on the floor. The camera pans around different areas of the town, showing all the places he may be lurking. If you’re down with the fact that it’s pretty obvious this is all an intentional love letter and not a bad rip-off, it’s pretty fun. Where Malevolence makes its own mark is in the true crime moments to follow. Law enforcement officers pull up to the plant and uncover a multitude of horrors. They find the notebooks of the original killer, which explain that he kidnapped the boy, taught him how to hunt, and was now being hunted by him. This also happened to be his final entry. We discover a hauntingly long line of bodies covered in white sheets: the bodies of the many missing persons the town had for years been searching for. And there are a whole lot of them. This moment really adds a cool layer of serial killer creepiness to the film.

Ultimately, Malevolence is a low-budget movie with some obvious deficiencies on full display. Enough of them that I can imagine many viewers giving up on the film before they get to what makes it so special, which probably explains how it has gone so far under the radar all these years. But the film is a wonderful ode to slashers that have come before it and still finds a way to bring an originality of its own by tying a bank robbery story into a slasher affair. Give Malevolence a chance the next time you’re in the mood for a nice little old school slasher movie.

Malevolence is now streaming on Tubi and Peacock.

You must be logged in to post a comment.