Editorials

Norman and Me: Discovering Myself in the Bates Motel

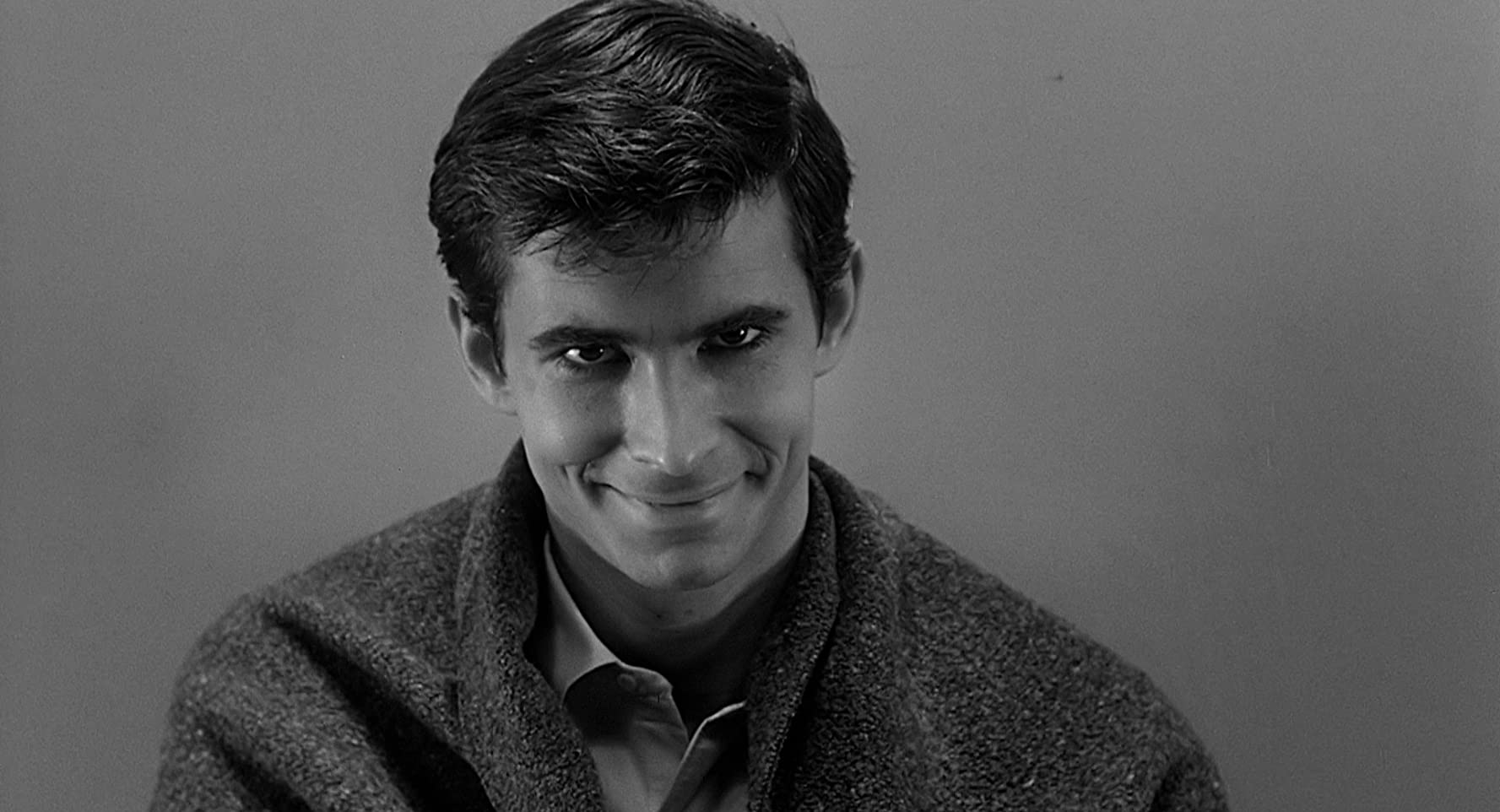

When I learned that filmmaker Sam Wineman was accepting submissions for his upcoming queer horror documentary, I knew immediately that I wanted to talk about Anthony Perkins. The original Psycho (1960) has long been one of my favorite movies, horror or otherwise, and Perkins is a huge part of that. As tormented mama’s boy Norman Bates, Perkins is immensely sympathetic and relatable, which makes the revelation that he’s the killer all the more shocking. Certainly I related to this young man who was different in some mysterious but undeniable way; I myself always felt different, so when I realized I was gay it provided the answer to a long-standing question. Back when I was a child and first watched Psycho and Psycho II (1983) on video—with my mother, appropriately enough—Norman resonated with me in a way I didn’t quite comprehend at the time. A mama’s boy myself, I have a long-running joke with my own mom—wonderful, supportive, and hilarious, nothing like the domineering shrew suggested by Psycho—that I’m Norman. As I wrote up my notes on Perkins for the documentary taping, I realized that it was through Tony and Split Image: The Life of Anthony Perkins, Charles Winecoff’s 1996 biography, that I actually learned about gay history, culture, and identity—and thus about myself. I had a dream about the actor in my early twenties. In the dream, Tony and I met and discussed what it was like to be a gay man in his lifetime versus mine. I woke up wondering if I had somehow actually met Perkins in my subconscious.

Norman Bates’ odd vulnerability, as beautifully rendered by Perkins, made him something of a folk hero, and the greatest modern example of the persecuted monster as sympathetic victim. This archetype is one of the reasons queer people have been historically drawn to the horror genre, and with Norman being portrayed by a closeted gay actor, the character gains an added resonance for LGBTQ audiences.

Norman has other queer qualities as well. He’s a shy, sensitive mama’s boy—gay men have historically had close relationships with their mothers, and an outdated “theory” of homosexuality is that it was caused by a suffocating mother. Two years after the release of Psycho, controversial psychiatrist Irving Bieber published Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals. As detailed in Split Image, Bieber wrote that “mothers of male homosexuals usually behave in … abnormal ways. They are overly intimate with their sons. They are also excessively possessive, over-protective and inclined to discourage the son’s masculine ways.” This sounds a lot like Mrs. Bates, who psychiatrist Dr. Richman describes as “a clinging, demanding woman.” Even after homosexuality was removed from DSM-III in 1973, Bieber protested “a homosexual is a person whose heterosexual function is crippled, like the legs of a polio victim.” This bizarre and demeaning view of gayness provides important context for the time in which Psycho was released and thus the reason we can “read” Norman as gay.

Norman’s sexuality is also mired in shame and secretiveness. He removes a painting depicting a rape to peep at Marion (Janet Leigh) in her underwear. The argument he has with his “mother” makes it clear that he’s been made to feel tremendous guilt over his sexual desires. “I won’t have you bringing strange young girls in here for supper—by candlelight, I suppose, in the cheap, erotic fashion of young men with cheap, erotic minds!” “she” declares.

In the film’s climax, Norman famously appears in drag and tries to stab Lila (Vera Miles) in the cellar, only to be restrained by Sam (John Gavin). Wanting to preserve his voice for his upcoming Broadway musical debut in Greenwillow, Perkins asked if he could pretend to scream and dub the sound in later. “Hitchcock liked the silent screams so much he never added the sound,” Perkins recalled. I later heard someone describe this moment as “the silent scream of gay men.” It’s utterly unintentional, of course, at least on a conscious level. But there’s something powerful and resonant in watching Perkins restrained by the manly Gavin, his face contorting in a shriek but yet unable to make a sound. I would never watch the scene the same way again. (Norman does have one line just prior to this scene, right as he appears in the doorway of the fruit cellar: “I am Norma Bates!” It was most likely recorded by actress Jeanette Nolan, one of several actors who recorded lines for “Mother.” Hitchcock blended them together for an uncanny quality.)

I read Winecoff’s Split Image as a freshman in high school, having not yet discovered my own sexuality. Certainly I was already a somewhat obsessive Psycho fan, so I was interested for that reason. But perhaps there was something more that drew me to the book, with its handsome cover photo of Perkins and its intimate details of his personal life. I learned that Perkins, like the author, was a gay man, and was forced to remain closeted for the sake of his film career. He later married photographer Berry Berenson and had two sons with her, musician Elvis Perkins and film director Oz Perkins (Gretel and Hansel). Winecoff provides at times explicit details of Perkins’ life with his male lovers, including fellow closeted matinee idol Tab Hunter, which I was surely intrigued and confused by at the time. The book also recounts Perkins’ battle with AIDS, which led to his death in 1992. I had been aware of AIDS as a child; in fact, Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia was the first “grownup” movie I saw in theaters (the film was released the year after Perkins died, when I was ten). But reading Split Image’s account of the crisis and Perkins’ passing was my first real education in AIDS’ devastating impact.

Perkins learned of his status from a 1990 National Enquirer headline, “PSYCHO STAR BATTLING AIDS VIRUS”; a lab technician had apparently tested his blood after he visited his doctor, and then sold the results. It was a cruel and fitting coda to a life spent running from the homophobic machinery of the Hollywood press. Winecoff explains that gay actors lived in fear of another trashy tabloid, Confidential, which loved nothing more than to “out” closeted stars during its heyday in the Fifties and Sixties. A source recalled to Winecoff how he’d once witnessed Perkins and Hunters’ clandestine car ride—in separate vehicles—to Hunter’s West Hollywood apartment. “I left a note on the seat of Tab’s convertible, with a drawing of two pansies intertwined,” the man remembers. After learning how fearful Hunter was of an expose in Confidential, he knocked on the actor’s door to apologize; “Tab was very cold.” I recalled this story one afternoon when my grandparents drove me home from school. We had pulled into a driveway to turn around, and I joked that I was home. My grandmother said that I wouldn’t want to claim this house, pointing out a floral flag out front. “You see those flowers?” she asked. “Those are pansies.” I understood the implication immediately, and it hurt. (I was closeted to her at the time.)

Because of Winecoff’s book, Perkins became my window into gay history and culture, and the way homosexuality has been mocked, repressed, and expressed over the years. It was the beginning of a lifelong interest in LGBTQ history. Perkins’ career was marked by a long history of queer coding, in which a character is never explicitly “written” as queer but can be read as such through subtle clues. Apart from Norman, Perkins played an early Broadway role in Elia Kazan’s Tea and Sympathy (1953), about a young college student suspected of homosexuality but “saved” by the love of a good woman. Then there was “Never Will I Marry,” his showstopper in Greenwillow (1960). Ostensibly about his character Gideon’s curse– to never settle down—“it became an instant camp classic within the invisible gay community because fey Anthony Perkins was singing it,” Winecoff writes. “Indeed, over the years it has proved an ironic theme song for the actor’s own surprising personal life.” The song was later covered by gay icons Barbara Streisand and Judy Garland.

About fifteen years ago, when I was living in Boston, I interviewed an older gay man as a possible roommate. He noticed that I had one of Perkins’ album covers on my wall and told me that he slept with the actor on Fire Island back in the day, not initially knowing who he was. His story encapsulated everything I had learned from Tony’s biography: “The next day he told me, ‘Yes, it’s me. Please don’t tell anyone.’”

In 2007, I saw Tony’s son Elvis perform on Coney Island and met him briefly at a CD signing afterwards. I appreciated his melancholy music, but I felt compelled to go because I knew it was the closest I’d ever come to meeting his late father.

Whether or not Perkins really visited my subconscious, he is truly immortal thanks to Norman Bates. The character’s legacy continued through three sequels, a 1998 remake, and the prequel series Bates Motel, which further explored the character’s ambiguous sexuality. (Actor Freddie Highmore was an outstanding choice to inherit Perkins’ torch.) The tormented and sympathetic Norman, and his portrayer, stand as a testament to the struggles and pain gay men endured to get to this point. I’ll never get to meet Tony, but I’ll forever be grateful to him.

Editorials

‘A Haunted House’ and the Death of the Horror Spoof Movie

Due to a complex series of anthropological mishaps, the Wayans Brothers are a huge deal in Brazil. Around these parts, White Chicks is considered a national treasure by a lot of people, so it stands to reason that Brazilian audiences would continue to accompany the Wayans’ comedic output long after North America had stopped taking them seriously as comedic titans.

This is the only reason why I originally watched Michael Tiddes and Marlon Wayans’ 2013 horror spoof A Haunted House – appropriately known as “Paranormal Inactivity” in South America – despite having abandoned this kind of movie shortly after the excellent Scary Movie 3. However, to my complete and utter amazement, I found myself mostly enjoying this unhinged parody of Found Footage films almost as much as the iconic spoofs that spear-headed the genre during the 2000s. And with Paramount having recently announced a reboot of the Scary Movie franchise, I think this is the perfect time to revisit the divisive humor of A Haunted House and maybe figure out why this kind of film hasn’t been popular in a long time.

Before we had memes and internet personalities to make fun of movie tropes for free on the internet, parody movies had been entertaining audiences with meta-humor since the very dawn of cinema. And since the genre attracted large audiences without the need for a serious budget, it made sense for studios to encourage parodies of their own productions – which is precisely what happened with Miramax when they commissioned a parody of the Scream franchise, the original Scary Movie.

The unprecedented success of the spoof (especially overseas) led to a series of sequels, spin-offs and rip-offs that came along throughout the 2000s. While some of these were still quite funny (I have a soft spot for 2008’s Superhero Movie), they ended up flooding the market much like the Guitar Hero games that plagued video game stores during that same timeframe.

You could really confuse someone by editing this scene into Paranormal Activity.

Of course, that didn’t stop Tiddes and Marlon Wayans from wanting to make another spoof meant to lampoon a sub-genre that had been mostly overlooked by the Scary Movie series – namely the second wave of Found Footage films inspired by Paranormal Activity. Wayans actually had an easier time than usual funding the picture due to the project’s Found Footage presentation, with the format allowing for a lower budget without compromising box office appeal.

In the finished film, we’re presented with supposedly real footage recovered from the home of Malcom Johnson (Wayans). The recordings themselves depict a series of unexplainable events that begin to plague his home when Kisha Davis (Essence Atkins) decides to move in, with the couple slowly realizing that the difficulties of a shared life are no match for demonic shenanigans.

In practice, this means that viewers are subjected to a series of familiar scares subverted by wacky hijinks, with the flick featuring everything from a humorous recreation of the iconic fan-camera from Paranormal Activity 3 to bizarre dance numbers replacing Katy’s late-night trances from Oren Peli’s original movie.

Your enjoyment of these antics will obviously depend on how accepting you are of Wayans’ patented brand of crass comedy. From advanced potty humor to some exaggerated racial commentary – including a clever moment where Malcom actually attempts to move out of the titular haunted house because he’s not white enough to deal with the haunting – it’s not all that surprising that the flick wound up with a 10% rating on Rotten Tomatoes despite making a killing at the box office.

However, while this isn’t my preferred kind of humor, I think the inherent limitations of Found Footage ended up curtailing the usual excesses present in this kind of parody, with the filmmakers being forced to focus on character-based comedy and a smaller scale story. This is why I mostly appreciate the love-hate rapport between Kisha and Malcom even if it wouldn’t translate to a healthy relationship in real life.

Of course, the jokes themselves can also be pretty entertaining on their own, with cartoony gags like the ghost getting high with the protagonists (complete with smoke-filled invisible lungs) and a series of silly The Exorcist homages towards the end of the movie. The major issue here is that these legitimately funny and genre-specific jokes are often accompanied by repetitive attempts at low-brow humor that you could find in any other cheap comedy.

Not a good idea.

Not only are some of these painfully drawn out “jokes” incredibly unfunny, but they can also be remarkably offensive in some cases. There are some pretty insensitive allusions to sexual assault here, as well as a collection of secondary characters defined by negative racial stereotypes (even though I chuckled heartily when the Latina maid was revealed to have been faking her poor English the entire time).

Cinephiles often claim that increasingly sloppy writing led to audiences giving up on spoof movies, but the fact is that many of the more beloved examples of the genre contain some of the same issues as later films like A Haunted House – it’s just that we as an audience have (mostly) grown up and are now demanding more from our comedy. However, this isn’t the case everywhere, as – much like the Elves from Lord of the Rings – spoof movies never really died, they simply diminished.

A Haunted House made so much money that they immediately started working on a second one that released the following year (to even worse reviews), and the same team would later collaborate once again on yet another spoof, 50 Shades of Black. This kind of film clearly still exists and still makes a lot of money (especially here in Brazil), they just don’t have the same cultural impact that they used to in a pre-social-media-humor world.

At the end of the day, A Haunted House is no comedic masterpiece, failing to live up to the laugh-out-loud thrills of films like Scary Movie 3, but it’s also not the trainwreck that most critics made it out to be back in 2013. Comedy is extremely subjective, and while the raunchy humor behind this flick definitely isn’t for everyone, I still think that this satirical romp is mostly harmless fun that might entertain Found Footage fans that don’t take themselves too seriously.

You must be logged in to post a comment.