Editorials

‘Tetsuo II: Body Hammer’ – Cyberpunk Body Horror Classic Spawned a Wild Sequel 30 Years Ago

Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992) isn’t so much a follow-up to his monochromatic frenzy of an original as it is a new approach to the same themes he explored in the first go around. 1989’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man is an industrial nightmare – a scouring pad to the grey matter. Body Hammer still retains Tsukamoto’s feverish energy he unleashed in the original film, but it’s in color this time – mostly grim greys and blues with dashes of vibrant orange, but color all the same.

Tomorowo Taguchi once again plays the titular role, this time inhabiting protagonist Taniguchi Tomoo. Taniguch is a mild mannered family man who just so happens to not remember his childhood before the age of 8, when he was adopted. Trying to recap the plot almost seems perfunctory; it’s not the plot we come to a Tetsuo film for, but the chaotic energy of Tsukamoto’s filmmaking. With that said, there is more of a traditional narrative through line in Body Hammer compared to its predecessor.

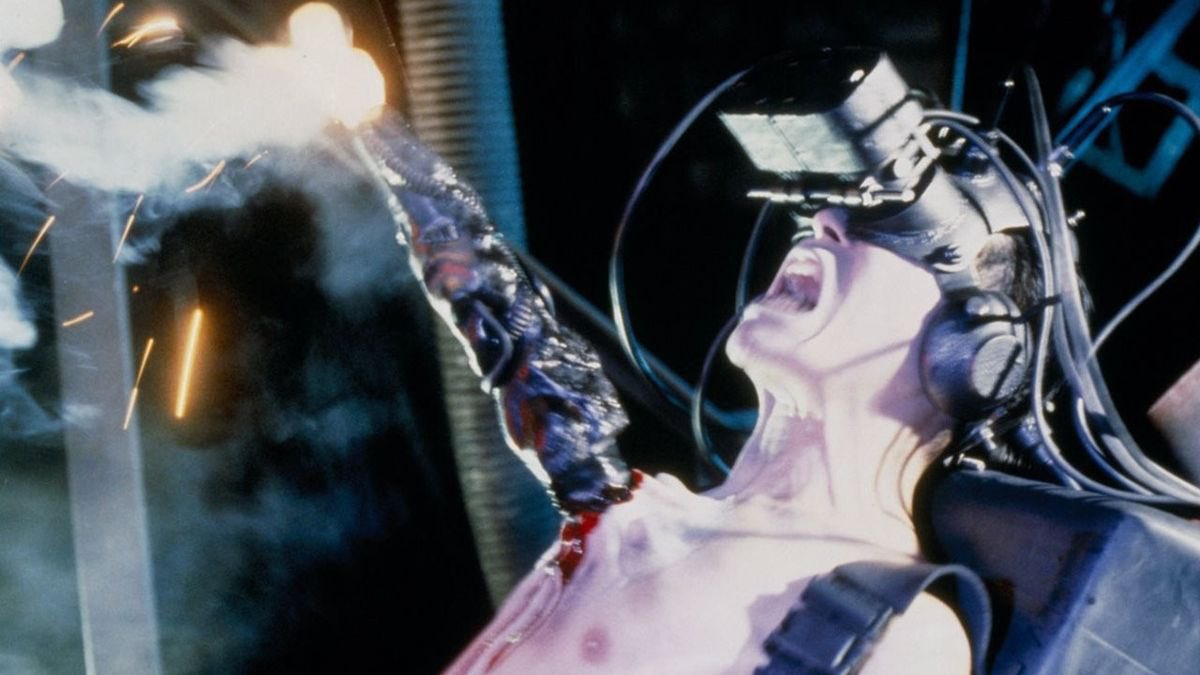

After Taniguchi’s son, Minori, is kidnapped by a gang of skinheads and Taniguchi is injected by something mysterious, he finds that in his rage and fear he can turn his body into a walking gun. His arm morphs into a canon and a multitude of gun barrels emerge from his chest – which he uses to riddle his enemies into a pulp.

Like the first film, the premise of Body Hammer is inherently absurd and the abrasive filmmaking style can feel like Tsukamoto screaming in your face for 80 minutes while Ministry blasts in the background, but that doesn’t make Body Hammer all punk rock style and no substance. Far from it. Much like its predecessor, Body Hammer isn’t concerned with making sure you’re on its wavelength. It just does its own thing and expects you to keep up.

Underneath the hectic energy, Body Hammer has a lot to say about the darkness of the human heart and the oppressive dread of the modern industrial world. Taniguchi’s powers are at first framed in a traditional action film lens. The hero was wronged, he gets powers, and we want to see him mess up the bad guys real good. As Body Hammer progresses, however, the familiar action film conceits warp into something far more tragic and perverse. As Taniguchi combats the skinhead gang who possess the same powers he does, you quickly realize the traditional narrative trappings of a hero’s rise to power and actualization are in reality latent childhood trauma finally allowed an outlet of escape. As his rage grows, as his memories emerge and revelations rear their head, Taniguchi becomes far more machine than man.

His aforementioned missing childhood memories reveal that his biomechanical power set have been with him his whole life from the abuse and experimentation perpetuated by his father on himself and his brother. At about the midway point Body Hammer transforms from a chaotic quasi-action film into a story of two brothers – Taniguchi and Yatsu (the leader of the skinhead gang) reconciling their childhoods. The comfortable thematic blanket of good guys and bad guys is ripped away, and we’re given a final act that is a clanking cacophony of images and sounds. The editing becomes so erratic, the body transformations become so inhuman, it’s difficult to even discern just what the hell is going on at some points. But despite Tsukamoto’s refusal to play by the rules, Body Hammer never becomes truly incomprehensible. By the end of the film, it actually reaches a certain profound sense of bittersweet triumph.

Tsukamoto is known for his explorations of the hell that is the modern industrial landscape. The Japan of Body Hammer is steely and alienating. The slate blue-gray, skyscrapers seem to take on an almost antagonistic presence as Tsukamoto’s editing constantly interjects them into the film. The camera swoops, dips, dives, twists, turns, and jitters from scene to scene. The relationship between man and metal in Body Hammer has a larger thematic scope to it than The Iron Man. The corruption and seduction of the steel, the rust, the gears, and the girders is generational. It’s in that subliminal space that Tetsuo II: Body Hammer finds its power.

Editorials

‘A Haunted House’ and the Death of the Horror Spoof Movie

Due to a complex series of anthropological mishaps, the Wayans Brothers are a huge deal in Brazil. Around these parts, White Chicks is considered a national treasure by a lot of people, so it stands to reason that Brazilian audiences would continue to accompany the Wayans’ comedic output long after North America had stopped taking them seriously as comedic titans.

This is the only reason why I originally watched Michael Tiddes and Marlon Wayans’ 2013 horror spoof A Haunted House – appropriately known as “Paranormal Inactivity” in South America – despite having abandoned this kind of movie shortly after the excellent Scary Movie 3. However, to my complete and utter amazement, I found myself mostly enjoying this unhinged parody of Found Footage films almost as much as the iconic spoofs that spear-headed the genre during the 2000s. And with Paramount having recently announced a reboot of the Scary Movie franchise, I think this is the perfect time to revisit the divisive humor of A Haunted House and maybe figure out why this kind of film hasn’t been popular in a long time.

Before we had memes and internet personalities to make fun of movie tropes for free on the internet, parody movies had been entertaining audiences with meta-humor since the very dawn of cinema. And since the genre attracted large audiences without the need for a serious budget, it made sense for studios to encourage parodies of their own productions – which is precisely what happened with Miramax when they commissioned a parody of the Scream franchise, the original Scary Movie.

The unprecedented success of the spoof (especially overseas) led to a series of sequels, spin-offs and rip-offs that came along throughout the 2000s. While some of these were still quite funny (I have a soft spot for 2008’s Superhero Movie), they ended up flooding the market much like the Guitar Hero games that plagued video game stores during that same timeframe.

You could really confuse someone by editing this scene into Paranormal Activity.

Of course, that didn’t stop Tiddes and Marlon Wayans from wanting to make another spoof meant to lampoon a sub-genre that had been mostly overlooked by the Scary Movie series – namely the second wave of Found Footage films inspired by Paranormal Activity. Wayans actually had an easier time than usual funding the picture due to the project’s Found Footage presentation, with the format allowing for a lower budget without compromising box office appeal.

In the finished film, we’re presented with supposedly real footage recovered from the home of Malcom Johnson (Wayans). The recordings themselves depict a series of unexplainable events that begin to plague his home when Kisha Davis (Essence Atkins) decides to move in, with the couple slowly realizing that the difficulties of a shared life are no match for demonic shenanigans.

In practice, this means that viewers are subjected to a series of familiar scares subverted by wacky hijinks, with the flick featuring everything from a humorous recreation of the iconic fan-camera from Paranormal Activity 3 to bizarre dance numbers replacing Katy’s late-night trances from Oren Peli’s original movie.

Your enjoyment of these antics will obviously depend on how accepting you are of Wayans’ patented brand of crass comedy. From advanced potty humor to some exaggerated racial commentary – including a clever moment where Malcom actually attempts to move out of the titular haunted house because he’s not white enough to deal with the haunting – it’s not all that surprising that the flick wound up with a 10% rating on Rotten Tomatoes despite making a killing at the box office.

However, while this isn’t my preferred kind of humor, I think the inherent limitations of Found Footage ended up curtailing the usual excesses present in this kind of parody, with the filmmakers being forced to focus on character-based comedy and a smaller scale story. This is why I mostly appreciate the love-hate rapport between Kisha and Malcom even if it wouldn’t translate to a healthy relationship in real life.

Of course, the jokes themselves can also be pretty entertaining on their own, with cartoony gags like the ghost getting high with the protagonists (complete with smoke-filled invisible lungs) and a series of silly The Exorcist homages towards the end of the movie. The major issue here is that these legitimately funny and genre-specific jokes are often accompanied by repetitive attempts at low-brow humor that you could find in any other cheap comedy.

Not a good idea.

Not only are some of these painfully drawn out “jokes” incredibly unfunny, but they can also be remarkably offensive in some cases. There are some pretty insensitive allusions to sexual assault here, as well as a collection of secondary characters defined by negative racial stereotypes (even though I chuckled heartily when the Latina maid was revealed to have been faking her poor English the entire time).

Cinephiles often claim that increasingly sloppy writing led to audiences giving up on spoof movies, but the fact is that many of the more beloved examples of the genre contain some of the same issues as later films like A Haunted House – it’s just that we as an audience have (mostly) grown up and are now demanding more from our comedy. However, this isn’t the case everywhere, as – much like the Elves from Lord of the Rings – spoof movies never really died, they simply diminished.

A Haunted House made so much money that they immediately started working on a second one that released the following year (to even worse reviews), and the same team would later collaborate once again on yet another spoof, 50 Shades of Black. This kind of film clearly still exists and still makes a lot of money (especially here in Brazil), they just don’t have the same cultural impact that they used to in a pre-social-media-humor world.

At the end of the day, A Haunted House is no comedic masterpiece, failing to live up to the laugh-out-loud thrills of films like Scary Movie 3, but it’s also not the trainwreck that most critics made it out to be back in 2013. Comedy is extremely subjective, and while the raunchy humor behind this flick definitely isn’t for everyone, I still think that this satirical romp is mostly harmless fun that might entertain Found Footage fans that don’t take themselves too seriously.

You must be logged in to post a comment.