Books

Killer Performances: ’90s Horror Books ‘The Stalker’ and ‘Stage Fright’ [Buried in a Book]

The theater is no doubt a stressful place to work. From technical difficulties to difficult talent, no production is without its troubles. Yet sometimes more than a good show is at risk — lives are threatened. This installment of Buried in a Book shines a spotlight on the unexpected horrors lurking behind the curtains.

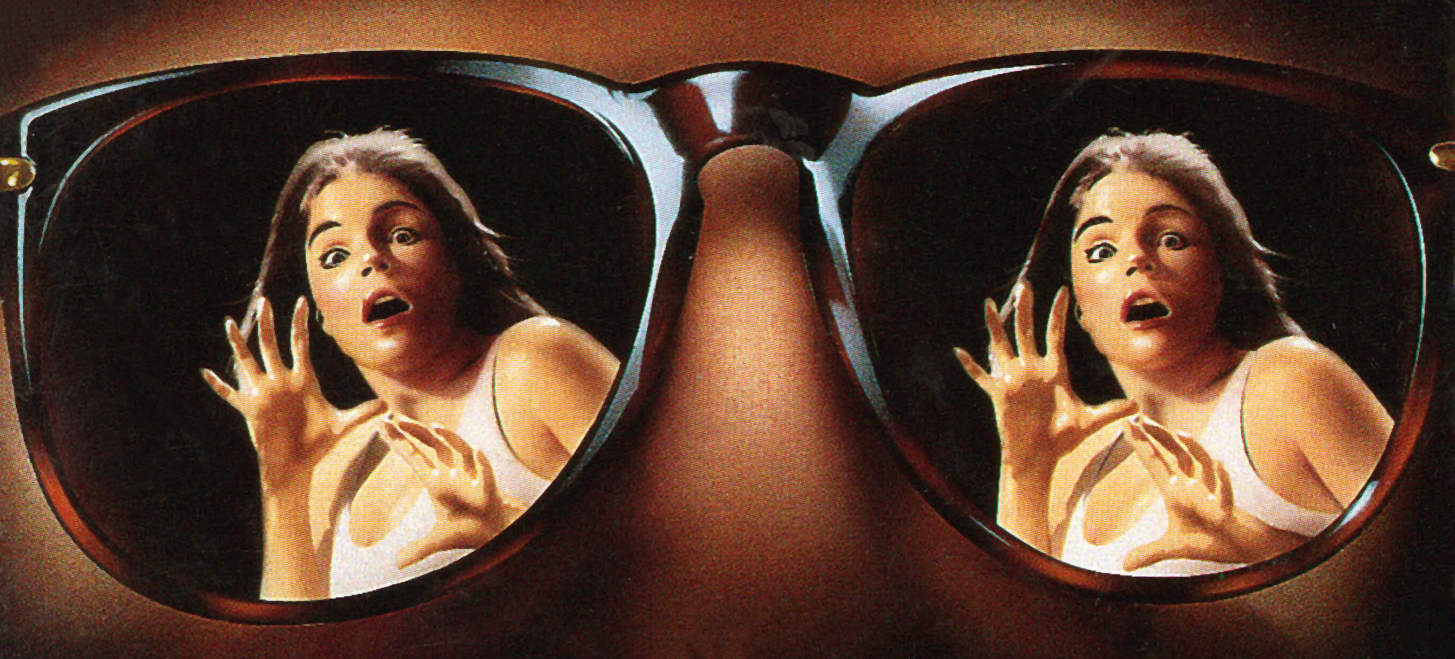

Jahnna N. Malcolm is the pen name for wife and husband Jahnna Beecham and Malcolm Hillgartner. The couple known for writing the children’s series The Jewel Kingdom previously collaborated on a collection of teenage thrillers called Zodiac. As the name implies, this strand of self-contained stories is based on the twelve astrological signs. The first volume, Stage Fright, sees a young Leo fall prey to an unusual predator.

In this 1995 book, a teen named Lydia Crenshaw is the queen bee at John Connally High School for the Performing Arts. She’s considered the best actor in these parts, and she’s all but guaranteed the lead role in the upcoming production of Evita. Lydia’s plans change, however, once she’s introduced to Page Adams; this prospective transfer student isn’t at all who she claims to be. Of course, by the time Lydia figures that out, her new “friend” has turned everyone against her as well as snatched her part in the new play.

The obvious inspiration for Stage Fright looks to be the 1992 suspense movie Single White Female, which itself is adapted from a 1990 novel called SWF Seeks Same. On the contrary, Jahnna N. Malcolm doesn’t lift anything significant from the movie, other than Page emulating Lydia’s clothes, makeup and hairstyle. In addition, Jennifer Jason Leigh’s character in Single White Female, Hedy, lashes out after feeling like she’s been rejected by Bridget Fonda’s character Allie; she wants her new roommate all to herself, so much so that Hedy kills everyone else in Allie’s life. Yet in Stage Fright, Page was never protective or possessive of Lydia; she only got close so she could then usurp Lydia’s life and friends.

Single White Female and Stage Fright both feature antagonists who mirror their targets. While not uncommon or always harmful, and it’s often done unconsciously, mirroring is also associated with people who have borderline personality disorder (BPD). Hedy’s mirroring is dramatic, stemming from an extremely vacant or distorted self-image. Page is evidently cut from a similar cloth; the authors describe her as having a “history of mental problems.” As with Hedy, Page is an example of how the media sensationalizes BPD for shock and entertainment, and how her condition is oversimplified so she can better fit the role of a villain. Stage Fright is a product of its time, but these kinds of insensitive depictions aren’t obsolete, even today.

Leos can be thought of as lively, theatrical and passionate. And as mentioned in the book, Leos are drawn to acting. Lydia, while talented, has an inflated ego and a huge sense of entitlement. The one good thing to come out of this Page situation is Lydia finally gains some modesty. She realizes how awful she was to her best friend, and she remembers how little time she’d spent with her younger brother since their parents’ divorce. Oddly enough, it’s only when Lydia almost loses her identity to someone else does she realize who she is, and what now needs to change.

Stage Fright doesn’t come with a lot of surprises; Page’s intentions are clear from the start. The book also caves to the standard, not to mention frustrating trope where the main character’s closest friends betray her without much thought or convincing. The story gives in to your expectations at every point. Meanwhile, Carol Ellis’ The Stalker is less predictable when unmasking the perpetrator. There’s more of a puzzle to solve in this 1996 book about a menaced chorus dancer.

Janna Richards, age 18, is touring with the Regional Theater Company when she’s singled out by a disturbed “fan.” An ominous drawing — the crude sketch is of a dancer with a broken leg — is followed by threatening phone calls, a butchered and bloodied toy, and a creepy message written in lipstick on Janna’s mirror. At first the protagonist believes her bitter ex-boyfriend, Jimmy Dare, is behind everything. He fesses to the drawing, but Jimmy denies the rest. So who could it be? Is it the obsessed Stan, who shows up to each of Janna’s performances? Or could it be Janna’s fellow dancer and rival, Liz?

The Stalker is a break away from the usual high-school environment in these kinds of books. It’s a step closer to the real world, but in place of college is now a traveling dance company. It’s only a regional performance of Grease, however the stalking storyline plays out differently since Janna is on her own and away from family. To make the transition more challenging, Janna dumps her toxic hometown boyfriend as well. Without the usual support systems to rely on, Janna is more vulnerable than other teens in comparable situations.

While she dances in front of audiences for a living, Janna doesn’t want to be watched without her consent or knowledge. The voyeurism of The Stalker ranges from Janna being looked upon by the assailant, who anonymously hides among a sea of theater patrons, to the flagrant act of peeping through a motel window. There’s a sick pleasure to the harasser’s methods that also feels intimate. He or she gets closer to Janna in a way that others can’t.

In both Stage Fright and The Stalker, the threat to the performer is intended to be a blurring of fantasy and reality. The theater is already a controlled meeting of the two, but not everyone understands the distinction once the show ends. There’s a startling emptiness to Page, one that she fills with others’ identities in order to be more “real.” As for Janna’s pursuer, really Stan’s jealous girlfriend Carly, she invents a scenario that puts all the blame on Janna rather than herself or her boyfriend. The truth is too painful to endure for these young villains, whereas the lies bring them comfort.

There was a time when the young-adult section of bookstores was overflowing with horror and suspense. These books were easily identified by their flashy fonts and garish cover art. This notable subgenre of YA fiction thrived in the ’80s, peaked in the ’90s, and then finally came to an end in the early ’00s. YA horror of this kind is indeed a thing of the past, but the stories live on at Buried in a Book. This recurring column reflects on the nostalgic novels still haunting readers decades later.

Books

‘Halloween: Illustrated’ Review: Original Novelization of John Carpenter’s Classic Gets an Upgrade

Film novelizations have existed for over 100 years, dating back to the silent era, but they peaked in popularity in the ’70s and ’80s, following the advent of the modern blockbuster but prior to the rise of home video. Despite many beloved properties receiving novelizations upon release, a perceived lack of interest have left a majority of them out of print for decades, with desirable titles attracting three figures on the secondary market.

Once such highly sought-after novelization is that of Halloween by Richard Curtis (under the pen name Curtis Richards), based on the screenplay by John Carpenter and Debra Hill. Originally published in 1979 by Bantam Books, the mass market paperback was reissued in the early ’80s but has been out of print for over 40 years.

But even in book form, you can’t kill the boogeyman. While a simple reprint would have satisfied the fanbase, boutique publisher Printed in Blood has gone above and beyond by turning the Halloween novelization into a coffee table book. Curtis’ unabridged original text is accompanied by nearly 100 new pieces of artwork by Orlando Arocena to create Halloween: Illustrated.

One of the reasons that The Shape is so scary is because he is, as Dr. Loomis eloquently puts it, “purely and simply evil.” Like the film sequels that would follow, the novelization attempts to give reason to the malevolence. More ambiguous than his sister or a cult, Curtis’ prologue ties Michael’s preternatural abilities to an ancient Celtic curse.

Jumping to 1963, the first few chapters delve into Michael’s childhood. Curtis hints at a familial history of evil by introducing a dogmatic grandmother, a concerned mother, and a 6-year-old boy plagued by violent nightmares and voices. The author also provides glimpses at Michael’s trial and his time at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, which not only strengthens Loomis’ motivation for keeping him institutionalized but also provides a more concrete theory on how Michael learned to drive.

Aside from a handful of minor discrepancies, including Laurie stabbing Michael in his manhood, the rest of the book essentially follows the film’s depiction of that fateful Halloween night in 1978 beat for beat. Some of the writing is dated — like a smutty fixation on every female character’s breasts and a casual use of the R-word — but it otherwise possesses a timelessness similar to its film counterpart. The written version benefits from expanded detail and enriched characters.

The addition of Arocena’s stunning illustrations, some of which are integrated into the text, creates a unique reading experience. The artwork has a painterly quality to it but is made digitally using vectors. He faithfully reproduces many of Halloween‘s most memorable moments, down to actor likeness, but his more expressionistic pieces are particularly striking.

The 224-page hardcover tome also includes an introduction by Curtis — who details the challenges of translating a script into a novel and explains the reasoning behind his decisions to occasionally subvert the source material — and a brief afterword from Arocena.

Novelizations allow readers to revisit worlds they love from a different perspective. It’s impossible to divorce Halloween from the film’s iconography — Carpenter’s atmospheric direction and score, Dean Cundey’s anamorphic cinematography, Michael’s expressionless mask, Jamie Lee Curtis’ star-making performance — but Halloween: Illustrated paints a vivid picture in the mind’s eye through Curtis’ writing and Arocena’s artwork.

Halloween: Illustrated is available now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.