Editorials

Writer Tony Burgess Heads Back to ‘Pontypool’ to Discuss Unmade Sequel ‘Pontypool Changes’ [Phantom Limbs]

phantom limb /ˈfan(t)əm’lim/ n. an often painful sensation of the presence of a limb that has been amputated.

Welcome to Phantom Limbs, a recurring feature which will take a look at intended yet unproduced horror sequels and remakes – extensions to genre films we love, appendages to horror franchises that we adore – that were sadly lopped off before making it beyond the planning stages. Here, we will be chatting with the creators of these unmade extremities to gain their unique insight into these follow-ups that never were, with the discussions standing as hopefully illuminating but undoubtedly painful reminders of what might have been.

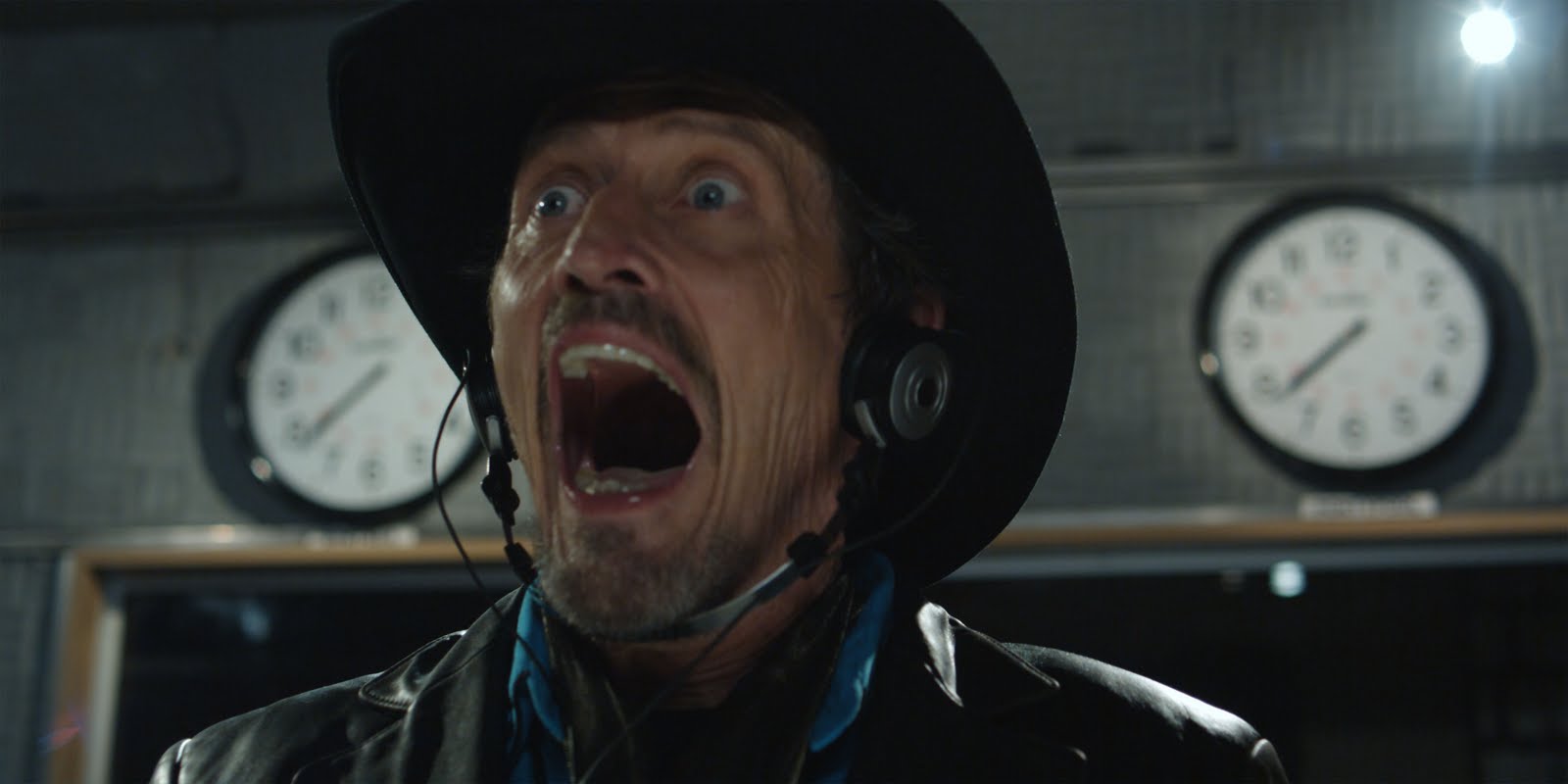

For this entry, we’ll be taking a look at Pontypool Changes, the as-yet unproduced sequel to the Bruce McDonald (Hard Core Logo)-directed 2008 horror film Pontypool. Penned by Tony Burgess, author of the source novel Pontypool Changes Everything, Pontypool told the story of Grant Mazzy (Stephen McHattie), a radio shock jock tasked with keeping the titular town fully informed during what appears to be an unfolding zombie apocalypse.

With its spare, one location production and small cast of characters, Pontypool made up for its limited scope with some big, challenging ideas regarding what a zombie film could be – chief among them being that the source of the viral infection which turns Pontypool’s residents into mindless zombies all stems from spoken language. Boasting sterling performances and some truly harrowing sequences, Pontypool left its viewers with an open ending, as well as an enigmatic post-credits sequence which raised even more questions than the film’s cliffhanger finale.

Unfortunately, the intended sequels (there was to be a trilogy) have yet to reach production. Bloody Disgusting sat down with Mr. Burgess to discuss the development of the first follow-up, the story it was meant to tell, and why it hasn’t yet happened. Along the way, we manage to chat about the planned third film, a radio play adaptation, and the bizarre, recently released companion film Dreamland.

“Everything is sort of inside out and backwards,” Mr. Burgess begins, discussing how the sequel to Pontypool was first mooted. “There are actually several [intended] sequels, but the major sequel is the first script that was written twenty years ago. Pontypool Changes, which is now called Typo Chan, was actually the first script. The original adaptation was more ambitious than the film that wound up getting made, which had a very small budget in a single space. So the first script had a larger budget, more locations, more of an ensemble cast – just a bigger canvas. That was very difficult to get off the ground, just because you’re asking people for a lot of money to make a Canadian zombie film, and that’s not easy to do. By a series of flukes, the CBC [Canadian Broadcasting Corporation] commissioned Bruce and I to make a radio play, based on a short treatment I’d written. We thought, ‘Well, we’re not getting this movie made, so we might as well do that.’ We ended up making the radio play, and in the middle of that, we thought, ‘Why not just bring in a camera and shoot it? Make it a feature?’ So that’s what happened there.”

So what story would this follow-up have told? “There’s a lot of intersection between the film Pontypool, in the radio station, and the original script, which is now the sequel [Pontypool Changes/Typo Chan]. It takes place in the town of Pontypool, simultaneous to the first film. That is, in the sequel, you see the people who are listening to the radio in the town. There are some intersections with characters, and some overlap. But it largely introduces new characters from the book. [There’s] a lot of stuff from the book.

“It takes some story elements from the book with the character of Les Reardon, who is staying at a farmhouse. He’s farmsitting for a family in Pontypool. He’s there, more or less, for a kind of geographical cure for a series of problems he’s had in his life. Mental illness, addiction, stuff like that. He’s taken a geographical cure by leaving the city and going to Pontypool and sit on a farm to do nothing, for a family that’s taken off for the winter.

“We soon learn that the cop across the street has taken an interest in him, because his wife is sort of a self help therapist who’d connected with [Les] online … and has some sort of connection with him. He’s suspicious, the cop, but he has no proof. We soon learn that – yeah, these two are pretty hot for each other, and they didn’t even know it until they’d laid eyes on each other. It begins this almost Postman Always Rings Twice, James Cain, small stakes betrayal in a small town kind of thing.”

As this film’s story largely happens in parallel to the events of the original film, Mr. Burgess points out that we were to see some returning characters sprinkled throughout this sequel. “It’s mostly audio, but [Grant Mazzy and fellow survivor/radio producer Sydney Briar] do have surprise appearances in both sequels. We have Grant Mazzy on the radio, taken exactly from the original, and then those strange events start to happen. And we’ll see some of them! We see the office of Dr. Mendez exploding, we see the fishing hut thing happen. It triangulates, almost. You’ve got the radio, you’ve got local gossip … you don’t have immediate access to information, you’re really just relying on the radio.

“The town, of course, spirals out of control in many ways. We’ve got road blocks with French police, and different sorts of things, along with [Reardon’s] strange sort of relationship with this woman where, along the way, they wind up picking up someone’s baby that they have to carry along. They become this weird kind of family in the middle of this small town apocalyptic world.

“It’s a much larger frame,” Mr. Burgess notes, comparing the sequel’s scope to that of the original film. “It happens in the same time period. Real time, same period. Some of the events, the fish hut and the Dr. Mendez stuff, that’s happening but it’s more in the periphery. It’s more about the central character and the events in the town, and we get a bigger picture as to what’s happening in the rest of the world outside of it. So we get a sense of how quickly the army is shutting down access to Pontypool, and that Pontypool is sort of Ground Zero. We go into suburban neighborhoods, and local diners, and hardware stores. We have new characters, so it’s bit more of an ensemble, a portrait of a town.

“Where it ends up is completely bizarre, and a little bit more like the post-credits scene than anything else,” Mr. Burgess admits, referencing the sequence from the first film which finds its leads playing entirely different characters in what appears to be a hardboiled, black and white noir. “It all ends up unraveling completely in an attempt to once again answer, ‘What does everything look like when everything changes?’ That, to me, is the constant question in the series.

“By the end of the sequel, it’s very difficult to confirm which world you’re in. There is a way of describing it, that we’ve come up to the end of the world and the nuclear bomb that’s destroyed Pontypool. But the form that takes is not that. The form that takes is very different than that. But just as much gets obliterated as when a bomb goes off.”

It’s at this point in the conversation that Mr. Burgess understandably stops shy of revealing more of the plot. “I’m not going to tell you how it ends! There’s a lot of violence and gore, but it reaches you indirectly in awful ways. There will be more information about the nature of the virus, but part of that goes to – who do you believe? Who knows, when you ask those questions? We’re experiencing that right now. Who knows what’s happening, and who do you believe? I’ve had endlesss discussions with people who say, ‘What are the rules of the virus? It’s the most important thing in any zombie or infection movie. You have to have a set of rules which are consistent.’ But that has absolutely nothing to do with the real world! In the real world, viruses break their rules all the time. The people who tell you the nature of those rules don’t actually know them.

“I’ve had these arguments for years and years with people, especially producers who want to come on and say ‘In order for everybody to understand how this movie works, we need to know the rules in the first ten minutes.’ And that’s typically how zombie or infection movies work. You learn the rules pretty quickly.

“I find that when I’m watching a film, the most interesting part is that period of uncertainty, that not knowing, that struggle, that race to access information. And how do you credit the speaker, how do you find a credible person to explain to you how this is working? That to me has always been the more interesting part. Once you’ve figured out all the rules, and it’s just about a siege in an attic or that kind of film, it’s just a war movie, really. Which is fine, and there are some great ones, but I’m always more interested in the buildup, the sort of creeping terror, being stripped of the ability to know, that’s always more interesting.

“Realizing you can’t know is much more disturbing and upsetting than discovering it. Discovering it is almost always a letdown, because it’s never really believable. It confirms, for me, that we’re in pure fantasy. As long as it doesn’t confirm things, we’re not necessarily in fantasy yet. So that to me is a much more frightening and truer place to linger in. That’s what we did with the original, and again with this second one. The third is even more spectacularly bizarre, but it’s my favorite one, really.”

Given the names of Mr. Burgess’ novel and the first film, one can see a progression beginning with the sequel’s initial title. So why the change to Typo Chan? Would the word Pontypool feature anywhere in this follow-up’s marketing to clue folks in on its status as the second film in a franchise? “It’s hard to say. You run into discussions all the time with stuff like that, especially with people coming up from the States who’re saying, ‘Well, the first thing you have to do is change the name from Pontypool to a small town in Michigan. Nobody will know what it means.’ Well, there’s already been a film named Pontypool that people have watched, and there’s interest generated by that, and … y’know, fuck you really! I stick to the title. To me, the reference always has to be to that small town and the original book. So Typo Chan itself is a reference to Pontypool Changes, and then the third one, right now as it stands, is going to be called Pontypool Changes Everything to cap it.

“The idea was, we’d go Pontypool, Pontypool Changes, and then Pontypool Changes Everything. That got a little bit too cute, maybe? The middle title, I didn’t like so much. Maybe it’s not bad, but it wasn’t really grabbing me. So we just sort of played around with it. I always liked the fact that the word ‘typo’ appears in the middle of the word Pontypool, so we just stripped that back. We liked the play of Typo Chan as a curious word pairing. It kind of has a ring to it, I think. Whether at the end of the day somebody pays us to change it, that can always happen. For my money, Typo Chan is the best title.”

And what of that third film? Mr. Burgess reveals that it not only has a title, but it’s been fully written for some time. “The third [film], tentatively titled Pontypool Changes Everything, was also conceived and written ten or twelve years ago. It’s my favorite version of all of them. It’s set in a post-Pontypool world, where there is viral weather that moves around through conversation and speech. So you have mutants and strains and all kinds of things that happen in language, then the antigens are … you beat back an infected alliteration by yelling for two days. Then the weather reports give you [instructions on how to combat the viral weather]. And then you have the rehab [featured in the final act of the first film, where our heroes discover how to use language to defeat the virus].”

Beyond these direct continuations, another film released in 2019 called Dreamland has some interesting connections to the world of Pontypool, in addition to having the creative team of Burgess/McDonald behind it. Mr. Burgess explains: “There is another sequel, the strangest sequel of all time, which is called Dreamland. It’s the most unlikely, tenuous type of sequel. We had this story we were playing around with, using the characters from that post-credits sequence to create a kind of magical, strange, noirish, junky world that they live in.”

But does Dreamland connect to the Pontypool narrative? “No, no. No, it doesn’t. People are going to push back on it because of that. The only connection, really, is that the characters seem loosely based on Johnny Deadeyes and Lisa the Killer [the characters featured in Pontypool’s post-credits scene, played by that film’s leads Stephen McHattie and Lisa Houle]. They have the same names, so they are the same characters. In that little brief glimpse you get of that world, in the post-credits sequence, that’s the world we go into. But it doesn’t have anything, other than that, to do with the Pontypool story or virus.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Burgess teases that the connections between the two properties may indeed extend beyond the superficial. “Now, one of the things that satisfies me, is the question that we’ve always had: ‘What happens if Pontypool changes everything?’ If you change everything, it cannot look like the thing you’ve changed it from. So, the true sequel to Pontypool should bear no resemblance to it. That, for me, satisfies that. We had many discussions, and we continue to have them, around where do you start if you change everything, and where do you stop? What does ‘everything change’ look like? Does looking change? There’s the one extreme, where you would say, ‘Well okay, if everything changes, let’s just make everybody purple and have buffaloes rain out of the sky.’ That’s the kind of Saturday Morning Cartoon version of everything changing. Then there’s the other end of it, where there’s nothing. No point of reference, no point of exchange between before and after, or nothing changed and everything changed. So it’s very hard to guide you into that. This hits somewhere on that spectrum there, in that – it not resembling Pontypool is possibly the best answer to a sequel, in my mind. Then you can begin discussions about what is happening on the screen, who are they, what is this world, where does it exist? The film doesn’t address that, other than to give you a kind of enigmatic vibe and an open-ended set of propositions around what is on the screen. That, to me, is fine. I’m interested in standing back and seeing what anybody would have to say about it.

“One of the things that it also satisfies for me is – so many screenings of Pontypool I’ve been to, where I was doing Q&As and whatever … invariably, somebody would say, ‘So what’s the deal with that post-credits thing? It really bugs me. Can you explain that?’ And my answer was that, ‘No, I can’t give an explanation, because the question itself makes me so angry,’ he laughs. “So Dreamland is a kind of version of an answer.”

So! A radio play, one produced feature film, two intended sequels, and a tenuously-connected companion film. Beyond those extensions of the original novel, Mr. Burgess reveals that he’s also working on a follow-up to the radio play. “The other thing I’m doing, it’s newer, I’m sort of doing it own my own. It’s a more direct sequel to the radio play. It’s an on-air weather network in the post-Pontypool world. So the whole thing takes place in the weather station. You’ve got all of these bizarre weather reports of, say, a front of bilabial plosives that are corrupt, and have to be beat back with a lot of hard C’s. Or whatever [laughs]. In the course of it, you have a kind of strange occurrence where there is a strain moving up from the south, from the States somewhere. It’s anomolous, unlike anything else. It’s not lethal, but it’s causing people to harmonize with people around them. So you have all these people harmonizing all over the place, and the harmonies are all traveling via the viral highway. They don’t know what it is. It’s reaching all kinds of intensities and becoming a bizarre, maddening choir of voices that’s growing in different sections of the populace. It becomes something interesting. The phrase ‘God bug’ becomes important…”

So, given the first film’s critical reception and cult status, why is it that we haven’t yet gotten Typo Chan or Pontypool Changes Everything? “One of the reasons … when Pontypool premiered in Canada, it was done in a kind of half-assed way. Its opening numbers were terrible, it wasn’t universally liked. It was sort of a head-scratcher that nobody went to see. The distributor ran it in a couple of suburban theatres without telling people what they were seeing, as a focus group test. They sent them in with cards. You know, ’Did you like this movie? What did you think of this movie?’ Almost every person came out of the film saying they had no idea what the film was about, they were totally confused, and they thought it was garbage.

“So it had a really rough start. The opening box office numbers were miserable. It took years for that film to make its money back. That’s a big part of what you need if you’re saying, ‘This film deserves a sequel with a bigger budget, and we need you to part with your money.’ That’s a hard sell, especially since the sequel is as challenging, or more challenging, to an audience. That’s why a lot of the discussions have been around how to conventionalize it into a more normal zombie story, which I’ve resisted. And Bruce has, too.

“It’s not that they aren’t happening. There’s always something happening with them. Right now, Bruce has a raft of really cool producers who are working on trying to get them made. I haven’t worked on them in a while. There is a very strong push to get them made, and some very good people are involved, so we’ll see what happens. My job is done, I’m just a spectator at this point.

“The current producers involved, I believe their heads are in the right place, and they want to make the right movie. But it still remains hard, because that model of the opening box office take and the success of the film financially is still key. That’s been the big reason. And partly because we’ve refused to create a more conventional answer to the first film.”

In closing out our chat, Mr. Burgess offers his final thoughts on Typo Chan: “I think it will satisfy the appetite for people who want to know more about what happened in the first film, but also be satisfying in that it won’t reveal everything. Like I said, I’m fairly comfortable now that my job is done there. Wake me up when it’s showtime!”

Very special thanks to Tony Burgess for his time and insights.

Editorials

‘A Haunted House’ and the Death of the Horror Spoof Movie

Due to a complex series of anthropological mishaps, the Wayans Brothers are a huge deal in Brazil. Around these parts, White Chicks is considered a national treasure by a lot of people, so it stands to reason that Brazilian audiences would continue to accompany the Wayans’ comedic output long after North America had stopped taking them seriously as comedic titans.

This is the only reason why I originally watched Michael Tiddes and Marlon Wayans’ 2013 horror spoof A Haunted House – appropriately known as “Paranormal Inactivity” in South America – despite having abandoned this kind of movie shortly after the excellent Scary Movie 3. However, to my complete and utter amazement, I found myself mostly enjoying this unhinged parody of Found Footage films almost as much as the iconic spoofs that spear-headed the genre during the 2000s. And with Paramount having recently announced a reboot of the Scary Movie franchise, I think this is the perfect time to revisit the divisive humor of A Haunted House and maybe figure out why this kind of film hasn’t been popular in a long time.

Before we had memes and internet personalities to make fun of movie tropes for free on the internet, parody movies had been entertaining audiences with meta-humor since the very dawn of cinema. And since the genre attracted large audiences without the need for a serious budget, it made sense for studios to encourage parodies of their own productions – which is precisely what happened with Miramax when they commissioned a parody of the Scream franchise, the original Scary Movie.

The unprecedented success of the spoof (especially overseas) led to a series of sequels, spin-offs and rip-offs that came along throughout the 2000s. While some of these were still quite funny (I have a soft spot for 2008’s Superhero Movie), they ended up flooding the market much like the Guitar Hero games that plagued video game stores during that same timeframe.

You could really confuse someone by editing this scene into Paranormal Activity.

Of course, that didn’t stop Tiddes and Marlon Wayans from wanting to make another spoof meant to lampoon a sub-genre that had been mostly overlooked by the Scary Movie series – namely the second wave of Found Footage films inspired by Paranormal Activity. Wayans actually had an easier time than usual funding the picture due to the project’s Found Footage presentation, with the format allowing for a lower budget without compromising box office appeal.

In the finished film, we’re presented with supposedly real footage recovered from the home of Malcom Johnson (Wayans). The recordings themselves depict a series of unexplainable events that begin to plague his home when Kisha Davis (Essence Atkins) decides to move in, with the couple slowly realizing that the difficulties of a shared life are no match for demonic shenanigans.

In practice, this means that viewers are subjected to a series of familiar scares subverted by wacky hijinks, with the flick featuring everything from a humorous recreation of the iconic fan-camera from Paranormal Activity 3 to bizarre dance numbers replacing Katy’s late-night trances from Oren Peli’s original movie.

Your enjoyment of these antics will obviously depend on how accepting you are of Wayans’ patented brand of crass comedy. From advanced potty humor to some exaggerated racial commentary – including a clever moment where Malcom actually attempts to move out of the titular haunted house because he’s not white enough to deal with the haunting – it’s not all that surprising that the flick wound up with a 10% rating on Rotten Tomatoes despite making a killing at the box office.

However, while this isn’t my preferred kind of humor, I think the inherent limitations of Found Footage ended up curtailing the usual excesses present in this kind of parody, with the filmmakers being forced to focus on character-based comedy and a smaller scale story. This is why I mostly appreciate the love-hate rapport between Kisha and Malcom even if it wouldn’t translate to a healthy relationship in real life.

Of course, the jokes themselves can also be pretty entertaining on their own, with cartoony gags like the ghost getting high with the protagonists (complete with smoke-filled invisible lungs) and a series of silly The Exorcist homages towards the end of the movie. The major issue here is that these legitimately funny and genre-specific jokes are often accompanied by repetitive attempts at low-brow humor that you could find in any other cheap comedy.

Not a good idea.

Not only are some of these painfully drawn out “jokes” incredibly unfunny, but they can also be remarkably offensive in some cases. There are some pretty insensitive allusions to sexual assault here, as well as a collection of secondary characters defined by negative racial stereotypes (even though I chuckled heartily when the Latina maid was revealed to have been faking her poor English the entire time).

Cinephiles often claim that increasingly sloppy writing led to audiences giving up on spoof movies, but the fact is that many of the more beloved examples of the genre contain some of the same issues as later films like A Haunted House – it’s just that we as an audience have (mostly) grown up and are now demanding more from our comedy. However, this isn’t the case everywhere, as – much like the Elves from Lord of the Rings – spoof movies never really died, they simply diminished.

A Haunted House made so much money that they immediately started working on a second one that released the following year (to even worse reviews), and the same team would later collaborate once again on yet another spoof, 50 Shades of Black. This kind of film clearly still exists and still makes a lot of money (especially here in Brazil), they just don’t have the same cultural impact that they used to in a pre-social-media-humor world.

At the end of the day, A Haunted House is no comedic masterpiece, failing to live up to the laugh-out-loud thrills of films like Scary Movie 3, but it’s also not the trainwreck that most critics made it out to be back in 2013. Comedy is extremely subjective, and while the raunchy humor behind this flick definitely isn’t for everyone, I still think that this satirical romp is mostly harmless fun that might entertain Found Footage fans that don’t take themselves too seriously.

You must be logged in to post a comment.