Movies

Special Feature: Year of the Wolf: 1981

With all the expected (and almost certainly short lived) hoopla surrounding Joe Johnston’s remake of The Wolf Man, I thought it might be interesting to reflect back upon something that happened twenty-nine years ago; a rare occurrence proven by the passage of time to be one of the great anomalies in the history of horror movies: The Year of the Wolf. Dig on Jonathan Dornellas’s article below!

First a few words about the creative team behind 2010’s remake of the immortal classic. The director, Joe Johnston, is no stranger to high profile films set in the past. He’s responsible for “The Rocketeer” (which fell heartbreakingly short of the greatness it was capable of achieving), “October Sky” and “Hidalgo”. While none of his films have been financial disasters, almost all have failed to deliver the expected box office dollars. His great strength as a filmmaker is crafting movies that look like old-fashioned, big budget Hollywood spectaculars, yet nearly all of his films seem to lack some vital essence. His biggest hit to date remains his first film: “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids” (which everyone from my generation remembers as the movie we went to go see because “Batman” was sold out). All things considered, I think he was an excellent choice to direct “The Wolfman”, and the fact that it’s set in 1880’s plays to Johnston’s strengths, provided he has a decent script to work with.

The screenplay is a collaboration between David Self and Andrew Kevin Walker. Self’s carrier is undistinguished — a very short list of credits consisting mostly of unoriginal material; one hopes he wasn’t chosen just because “The Haunting” was a huge hit (he wrote the screenplay for that horrible 1999 remake of the Shirley Jackson classic). Andrew Kevin Walker’s best known original work is “Se7en” but he also wrote the underrated “8MM” (which I believe was inspired by Paul Schrader’s similarly underrated “Hardcore”). Although he hasn’t written much produced material since the late 90s, I think Walker’s take on the Wolf Man story could be a very interesting one.

The only other member of the creative team who warrants mentioning here is special effects makeup artist Rick Baker. I have yet to see Baker’s finished work on the Wolf Man, but there is no doubt that this was a dream project for him. The original Wolf Man, of course, was one of the Four Great Universal Monsters, and the transformation scenes inspired generations of special effect makeup artists.

Which brings us to the Year of the Wolf: 1981. The year that saw the release of “The Howling” and “An American Werewolf in London” and “Wolfen”. All three movies dealt with the subject of werewolves in three very different, intriguing ways.

It should be remembered that this spike in lycanthropy occurred during the absolute height of the Slasher Craze: “Halloween II” was the biggest horror hit of the year, followed closely by “Friday the 13th Part 2”, followed by all kinds of holiday-themed imitators. Which makes this historical anomaly all the more curious: there was no clear financial incentive to produce a werewolf movie, yet three of the greatest werewolf movies of all time were released that year.

“The Howling” originated as a 1977 novel by Gary Bradner. It was marketed as an occult tale “in the tradition of Salem’s Lot” (it says this on the back cover; some years ago I obtained a dog-eared copy from Ebay), and to this end it even borrows the idea of the nearly pitch black cover used famously on the first few paperback editions of Stephen King’s influential account of vampirism. “Salem’s Lot” of course was a huge bestseller, and the 1979 mini-series was a ratings winner, so it makes sense that “The Howling” was optioned around this time (perhaps solely on the strength of the easily pitchable “Salem’s Lot with Werewolves” concept). The project eventually fell into the lap of Joe Dante, whose previous film “Piranha” was one of the better (and funniest) “JAWS” rip-offs.

Here’s where things get interesting. “An American Werewolf in London” was already in pre-production as Dante assembled his “Howling” team. Bradner’s novel was eventually completely tossed in favor of an original script by John Sayles (nearly nothing from the novel, which wasn’t particularly well written, made it into the film apart from the title and the general idea of werewolves). Dante originally approached Rick Baker to do the werewolf makeup, and from the beginning the transformation scenes were intended to be one of the film’s selling points. Apparently Baker agreed to work on “The Howling” in tandem with his work on “American Werewolf”. But when John Landis got wind of this arrangement, the young “Animal House” director wasn’t pleased. Landis threw a fit, prompting Baker to quickly back away from any involvement with “The Howling”.

This created an opening for Rob Bottin, the twenty-year-old wunderkind who had previously worked with Dante on “Piranha”. Bottin was very much Baker’s protégé — the young man who, by all available accounts, had learned everything he knew about special effects makeup from Baker, who had hired Bottin when he was just fourteen-years-old.

One gets the sense that Baker, still a young man himself in those days, was something of a father figure to Bottin. They worked together on big budget projects like “Star Wars” and the underrated 1976 remake of “King Kong”. Bottin was Baker’s most gifted student, but Baker was very much the boss of his own shop. Young Rob often felt stifled, and increasingly frustrated each time his creative ideas were vetoed in favor of Baker’s own. Rob Bottin, unbeknownst to Rick Baker, had something to prove to the world. “The Howling” was a golden opportunity for him to demonstrate that his skills were equal, if not superior, to his mentor’s.

The stage was now set to see who could create the best werewolf the movies had ever seen, and the race was on.

It’s easy to assume Baker encouraged Bottin to branch off on his own, but twenty-nine years worth of interviews and accounts from various people involved in the Great Werewolf Race suggests otherwise. There’s a curious lack of documentation when it comes to Baker’s opinion of Bottin’s “Howling” work. It’s a very touchy subject to this day.

The fact is Baker felt betrayed by Bottin, not only for abruptly quitting Rick’s shop, but also for smuggling many of Rick’s “American Werewolf” techniques into “The Howling”. Rick had given Rob his first job and taught him all the tricks of the trade. Rob’s defection had to feel like a punch in the gut.

At the same time, Baker probably expected Bottin to fall on his face; his protégé was just too young and too temperamental to make it on his own in the movie business. And Baker possessed one vital skill which he knew Bottin essentially lacked: the ability to work well with others.

In terms of the Werewolf Race, Baker had a head start, an experienced team, and more money to work with. But Bottin possessed one key advantage over his former teacher: near total creative freedom. And as Rob Bottin has proven over the years, when given such freedom, he delivers incredible, sometimes legendary work. Baker’s design had to conform to specific characteristics ordered by John Landis. Bottin was allowed to do whatever he wanted to, and what he wanted to do was create the most amazing werewolf transformation of all time.

At first, the reach of both wolf designers very much exceeded their grasp. They have both stated that they initially desired to show one continuous transformation WITHOUT CUTTING AWAY; a goal which was essentially impossible in 1981. Both quickly realized this.

The transformation scene in “The Howling” is the scarier of the two, and totally unlike anything ever before seen in film up to that time. The transformation begins after a character says “Let me give you a piece of my mind” and proceeds to pluck a morsel of brain out of a bullet wound on his forehead. The use of standard horror movie fare — shadows and sound effects and creepy music — greatly enhance the impact of what we see, which includes bubbling skin, cracking bones, growing fingernails, growing teeth, growing ears, an elongating snout. Bottin became obsessed (to the amusement of Dante and his cinematographer) with his designs being carefully masked with the use of darkness and shadows. Rick Baker, on the other hand, intended to show his transformation in a bright, well-lit room.

“An American Werewolf in London” was made for one reason: John Landis wanted to make it. He wrote the script for the film back in 1969 and originally wanted it to be his follow-up to “Schlock”, but Landis was a nobody in Hollywood until the enormous popular success of “Animal House” in 1978. After that he could write his own ticket for a while. Even after “The Blues Brothers” underperformed, Landis was one of the hottest young directors in the business. “American Werewolf” would be a radical, bloody departure from his previous work.

Which isn’t to say the film wasn’t funny. To this day, I honestly don’t think any film has *ever* blended comedy and horror as effectively as Landis did in “American Werewolf”. He achieved a near pitch perfect balance between the two, yet people who don’t like the film generally cite the use of humor as their biggest criticism. In some ways, however, the film is actually darker than either “The Howling” or “Wolfen”.

None of the films in the Year of the Wolf end on a particularly hopeful note, and things do not turn out well for either of our appealing protagonists. “American Werewolf” has one of the most jarringly abrupt conclusions I’ve ever seen — he’s dead; the end; get out. “The Howling” ends with my single favorite closing shot ever.

The transformation scene in “American Werewolf” takes place in a brightly lit room; the standard horror movie fare utilized so effectively in “The Howling” — spooky shadows and creepy music — isn’t to be found here. And while I think the transformation in Dante’s film is the scarier of the two, “American Werewolf” is the easily the more disturbing of the two.

What struck me the most about the latter transformation had nothing to do with special effects — the thing that made the biggest impression on me when I first saw it was the fact that the character is *screaming in agony* while he changes. This was, as far as I know, a first. Previously in films where the lap dissolve was used to depict the metamorphosis, you never got the sense that turning into a werewolf was a painful process.

Many of the techniques used in “The Howling” are on display here — the elongating snout, the growing ears, the growing hair, etc. The biggest stylistic difference between the two is that the skin on Bottin’s creature *bubbles* while the skin on Baker’s creature *stretches*.

To this day, fans are very much divided over who crafted the best werewolf. Both transformations were brilliantly executed; trying to accurately gauge which one is liked best is as futile as attempting to resolve the IMDB Shawshank-Godfather calculation. It’s too close to call. And this is another aspect that makes the Year of the Wolf so fascinating; neither film is clearly superior to the other. All three are very good movies. I personally think “An American Werewolf in London” is a better film overall, but I prefer Bottin’s werewolf design over Baker’s. Both werewolves, however, are actually scary creatures — and there’s nothing more important than that in a werewolf movie.

The key stylistic design element ordered by Landis was that his werewolf be a four legged creature — he wanted it to be a demonic hound from hell, and Baker certainly achieved the look his director demanded. This werewolf is a *monster* in every sense of the word — it looks like a cross between a wolf, a bear, and a lion — a hideous hybrid escaped from the book of Revelation.

Bottin gives us a nightmare on two legs — a rabid version of the Big Bad Wolf who menaced the Three Little Pigs. For my money (all fifty cents of it) Bottin’s creation represents the quintessential werewolf — the most satisfying version of the mythological creature I’ve ever seen. Which is not to say the Bottin design is flawless — seen from a distance the creature looks rather absurd (the same is true for the alien in Ridley Scott’s 1979 masterpiece–the moment the monster looks like a man in a suit, it loses some of its impact).

The film that is always overlooked when discussing the Year of the Wolf is “Wolfen”. Some would argue that it’s not really a werewolf film at all (for reasons I won’t touch upon here), but I absolutely disagree with that view. Of the three films, “Wolfen” actually has the best story, and is far more suspenseful than its special-effects laden brethren.

Something of an anomaly within an anomaly, “Wolfen” has its roots in the mind of Whitley Strieber, best known for his supposedly non-fiction tome “Communion” — an account of his abduction by aliens in 1985. Before going off the deep end, Strieber wrote “Wolfen” which was published in 1978. The novel was adapted into a screenplay by Michael Wadleigh, who also directed the film. Wadleigh is an enigmatic character in his own right, whose only other film credit to date is the groundbreaking documentary “Woodstock”.

“Wolfen” is a nerve-jangling experience and contains a genuinely intriguing mystery (complete with perfectly legitimate red-herrings) — and while the final truth cancels out some of the thrills, it remains an entertaining experience throughout. Those who dislike the film generally fault the conclusion, and have little patience for Wadleigh’s rationalizations about man’s callousness toward nature.

All of three films of the Year of the Wolf were mildly successful, but none of them came close to matching the success of the holiday-themed slasher movies, so the Wolf Trend lived and died in 1981.

Of the three, “The Howling” can be considered the most successful financially, making all of its money back and then some. It had the lowest budget of the three films, and took a big chance by hiring a kid who wasn’t even old enough to buy alcohol to do the special effects. Almost everyone connected with the film went on to bigger and better things. The star, Dee Wallace, jumped out of the “Howling” and into “E.T.” Joe Dante’s talent was noticed by Steven Spielberg, who hired him to direct the phenomenally successful “Gremlins”. And Rob Bottin became an overnight star.

For all practical purposes, Bottin won the Great Werewolf Race of 1981. The incredible footage of his transformation sequences reached the media first, while Baker’s work remained strictly under wraps (on orders from John Ladis) almost until the film’s release, which hit theaters nearly five months after “The Howling”.

Bottin would go on to do perhaps the greatest pre-CGI special effects movie of all time — John Carpenters classic 1982 remake of “The Thing”, another project on which he was given near-total creative freedom. He would find less freedom on subsequent projects, and often clashed with high profile directors like Paul Verhoeven. He was originally chosen to write and direct “Freddy Vs. Jason”, which rolled around in development hell for years, but finally decided he wasn’t interested. In recent years he’s become a veritable recluse — Joe Dante couldn’t reach him to secure his involvement in “The Howling” Special Edition DVD a few years ago, and compares Bottin to Howard Hughes. His list of credits after 2000 dwindles to essentially nothing. One gets the sense he has nothing left to prove.

“An American Werewolf in London” was a financial disappointment for John Landis, who was perhaps spoiled by the mind-boggling success “Animal House”. The 80s would be a trying time for Landis, and despite scoring some big hits with Eddie Murphy, the creative ferocity of his early work would never return.

Baker won the first ever Academy Award for Makeup for his “American Werewolf” work, and has gone on to win even more over the years. Taking his entire body of work into account, a strong case could be made that Rick Baker is the greatest special effect makeup artist of all time. Unlike Bottin, Baker has made himself consistently available to the media, and is always happy to talk about his work on “American Werewolf”. On the Special Edition DVD of that movie, he muses that he’d like another shot at doing a werewolf. He got one.

A few months ago Baker expressed concerns that some of his werewolf makeup would be replaced with CGI enhancements. While I have yet to see the film, the trailer clearly shows that his concern was justified. Not that you can really fault the producers for utilizing a tool that today’s moviegoers have come to accept. The good old days are over.

Or are they? For at least the past ten years, movies have been pillaging the past for material. “The Wolf Man” and the upcoming “Elm Street” remake underscore the desperate lack of originality which prevails today. The Year of the Wolf represents a brief shining moment of abundant excellence in horror history that likely will never be repeated. A movie should be made about the Great Werewolf Race.

-Jonathan Dornellas

Editorials

Five Serial Killer Horror Movies to Watch Before ‘Longlegs’

Here’s what we know about Longlegs so far. It’s coming in July of 2024, it’s directed by Osgood Perkins (The Blackcoat’s Daughter), and it features Maika Monroe (It Follows) as an FBI agent who discovers a personal connection between her and a serial killer who has ties to the occult. We know that the serial killer is going to be played by none other than Nicolas Cage and that the marketing has been nothing short of cryptic excellence up to this point.

At the very least, we can assume NEON’s upcoming film is going to be a dark, horror-fueled hunt for a serial killer. With that in mind, let’s take a look at five disturbing serial killers-versus-law-enforcement stories to get us even more jacked up for Longlegs.

MEMORIES OF MURDER (2003)

This South Korean film directed by Oscar-winning director Bong Joon-ho (Parasite) is a wild ride. The film features a handful of cops who seem like total goofs investigating a serial killer who brutally murders women who are out and wearing red on rainy evenings. The cops are tired, unorganized, and border on stoner comedy levels of idiocy. The movie at first seems to have a strange level of forgiveness for these characters as they try to pin the murders on a mentally handicapped person at one point, beating him and trying to coerce him into a confession for crimes he didn’t commit. A serious cop from the big city comes down to help with the case and is able to instill order.

But still, the killer evades and provokes not only the police but an entire country as everyone becomes more unstable and paranoid with each grizzly murder and sex crime.

I’ve never seen a film with a stranger tone than Memories of Murder. A movie that deals with such serious issues but has such fallible, seemingly nonserious people at its core. As the film rolls on and more women are murdered, you realize that a lot of these faults come from men who are hopeless and desperate to catch a killer in a country that – much like in another great serial killer story, Citizen X – is doing more harm to their plight than good.

Major spoiler warning: What makes Memories of Murder somehow more haunting is that it’s loosely based on a true story. It is a story where the real-life killer hadn’t been caught at the time of the film’s release. It ends with our main character Detective Park (Song Kang-ho), now a salesman, looking hopelessly at the audience (or judgingly) as the credits roll. Over sixteen years later the killer, Lee Choon Jae, was found using DNA evidence. He was already serving a life sentence for another murder. Choon Jae even admitted to watching the film during his court case saying, “I just watched it as a movie, I had no feeling or emotion towards the movie.”

In the end, Memories of Murder is a must-see for fans of the subgenre. The film juggles an almost slapstick tone with that of a dark murder mystery and yet, in the end, works like a charm.

CURE (1997)

If you watched 2023’s Hypnotic and thought to yourself, “A killer who hypnotizes his victims to get them to do his bidding is a pretty cool idea. I only wish it were a better movie!” Boy, do I have great news for you.

In Cure (spoilers ahead), a detective (Koji Yakusho) and forensic psychologist (Tsuyoshi Ujiki) team up to find a serial killer who’s brutally marking their victims by cutting a large “X” into their throats and chests. Not just a little “X” mind you but a big, gross, flappy one.

At each crime scene, the murderer is there and is coherent and willing to cooperate. They can remember committing the crimes but can’t remember why. Each of these murders is creepy on a cellular level because we watch the killers act out these crimes with zero emotion. They feel different than your average movie murder. Colder….meaner.

What’s going on here is that a man named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) is walking around and somehow manipulating people’s minds using the flame of a lighter and a strange conversational cadence to hypnotize them and convince them to murder. The detectives eventually catch him but are unable to understand the scope of what’s happening before it’s too late.

If you thought dealing with a psychopathic murderer was hard, imagine dealing with one who could convince you to go home and murder your wife. Not only is Cure amazingly filmed and edited but it has more horror elements than your average serial killer film.

MANHUNTER (1986)

In the first-ever Hannibal Lecter story brought in front of the cameras, Detective Will Graham (William Petersen) finds his serial killers by stepping into their headspace. This is how he caught Hannibal Lecter (played here by Brian Cox), but not without paying a price. Graham became so obsessed with his cases that he ended up having a mental breakdown.

In Manhunter, Graham not only has to deal with Lecter playing psychological games with him from behind bars but a new serial killer in Francis Dolarhyde (in a legendary performance by Tom Noonan). One who likes to wear pantyhose on his head and murder entire families so that he can feel “seen” and “accepted” in their dead eyes. At one point Lecter even finds a way to gift Graham’s home address to the new killer via personal ads in a newspaper.

Michael Mann (Heat, Thief) directed a film that was far too stylish for its time but that fans and critics both would have loved today in the same way we appreciate movies like Nightcrawler or Drive. From the soundtrack to the visuals to the in-depth psychoanalysis of an insanely disturbed protagonist and the man trying to catch him. We watch Graham completely lose his shit and unravel as he takes us through the psyche of our killer. Which is as fascinating as it is fucked.

Manhunter is a classic case of a serial killer-versus-detective story where each side of the coin is tarnished in their own way when it’s all said and done. As Detective Park put it in Memories of Murder, “What kind of detective sleeps at night?”

INSOMNIA (2002)

Maybe it’s because of the foggy atmosphere. Maybe it’s because it’s the only film in Christopher Nolan’s filmography he didn’t write as well as direct. But for some reason, Insomnia always feels forgotten about whenever we give Nolan his flowers for whatever his latest cinematic achievement is.

Whatever the case, I know it’s no fault of the quality of the film, because Insomnia is a certified serial killer classic that adds several unique layers to the detective/killer dynamic. One way to create an extreme sense of unease with a movie villain is to cast someone you’d never expect in the role, which is exactly what Nolan did by casting the hilarious and sweet Robin Williams as a manipulative child murderer. He capped that off by casting Al Pacino as the embattled detective hunting him down.

This dynamic was fascinating as Williams was creepy and clever in the role. He was subdued in a way that was never boring but believable. On the other side of it, Al Pacino felt as if he’d walked straight off the set of 1995’s Heat and onto this one. A broken and imperfect man trying to stop a far worse one.

Aside from the stellar acting, Insomnia stands out because of its unique setting and plot. Both working against the detective. The investigation is taking place in a part of Alaska where the sun never goes down. This creates a beautiful, nightmare atmosphere where by the end of it, Pacino’s character is like a Freddy Krueger victim in the leadup to their eventual, exhausted death as he runs around town trying to catch a serial killer while dealing with the debilitating effects of insomnia. Meanwhile, he’s under an internal affairs investigation for planting evidence to catch another child killer and accidentally shoots his partner who he just found out is about to testify against him. The kicker here is that the killer knows what happened that fateful day and is using it to blackmail Pacino’s character into letting him get away with his own crimes.

If this is the kind of “what would you do?” intrigue we get with the story from Longlegs? We’ll be in for a treat. Hoo-ah.

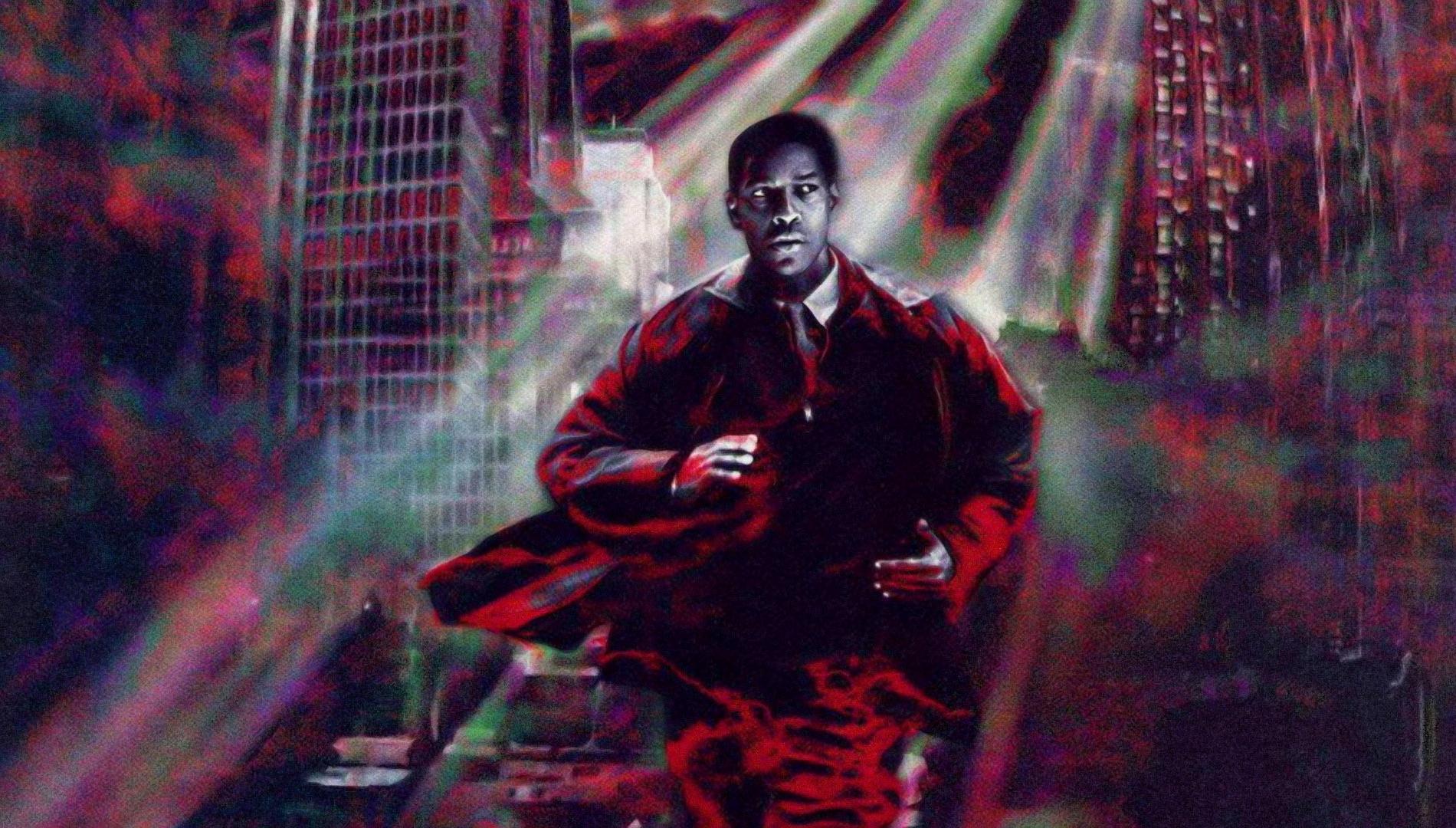

FALLEN (1998)

Fallen may not be nearly as obscure as Memories of Murder or Cure. Hell, it boasts an all-star cast of Denzel Washington, John Goodman, Donald Sutherland, James Gandolfini, and Elias Koteas. But when you bring it up around anyone who has seen it, their ears perk up, and the word “underrated” usually follows. And when it comes to the occult tie-ins that Longlegs will allegedly have? Fallen may be the most appropriate film on this entire list.

In the movie, Detective Hobbs (Washington) catches vicious serial killer Edgar Reese (Koteas) who seems to place some sort of curse on him during Hobbs’ victory lap. After Reese is put to death via electric chair, dead bodies start popping up all over town with his M.O., eventually pointing towards Hobbs as the culprit. After all, Reese is dead. As Hobbs investigates he realizes that a fallen angel named Azazel is possessing human body after human body and using them to commit occult murders. It has its eyes fixated on him, his co-workers, and family members; wrecking their lives or flat-out murdering them one by one until the whole world is damned.

Mixing a demonic entity into a detective/serial killer story is fascinating because it puts our detective in the unsettling position of being the one who is hunted. How the hell do you stop a demon who can inhabit anyone they want with a mere touch?!

Fallen is a great mix of detective story and supernatural horror tale. Not only are we treated to Denzel Washington as the lead in a grim noir (complete with narration) as he uncovers this occult storyline, but we’re left with a pretty great “what would you do?” situation in a movie that isn’t afraid to take the story to some dark places. Especially when it comes to the way the film ends. It’s a great horror thriller in the same vein as Frailty but with a little more detective work mixed in.

Look for Longlegs in theaters on July 12, 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.