Editorials

The Horror of the Ticking Clock in ‘Dead Rising’

Time Pressure is defined as a form of psychological stress that occurs when an individual has less time available than they would need (or deem necessary) to complete a task, job, or some sort of process that involves results. This lack of time can be either real or perceived, and when confronted with this lack of time, an individual gains a certain sense of tunnel vision—complete the task at hand while other things can fall by the wayside. Frank West from Dead Rising knows a thing or two about time pressure.

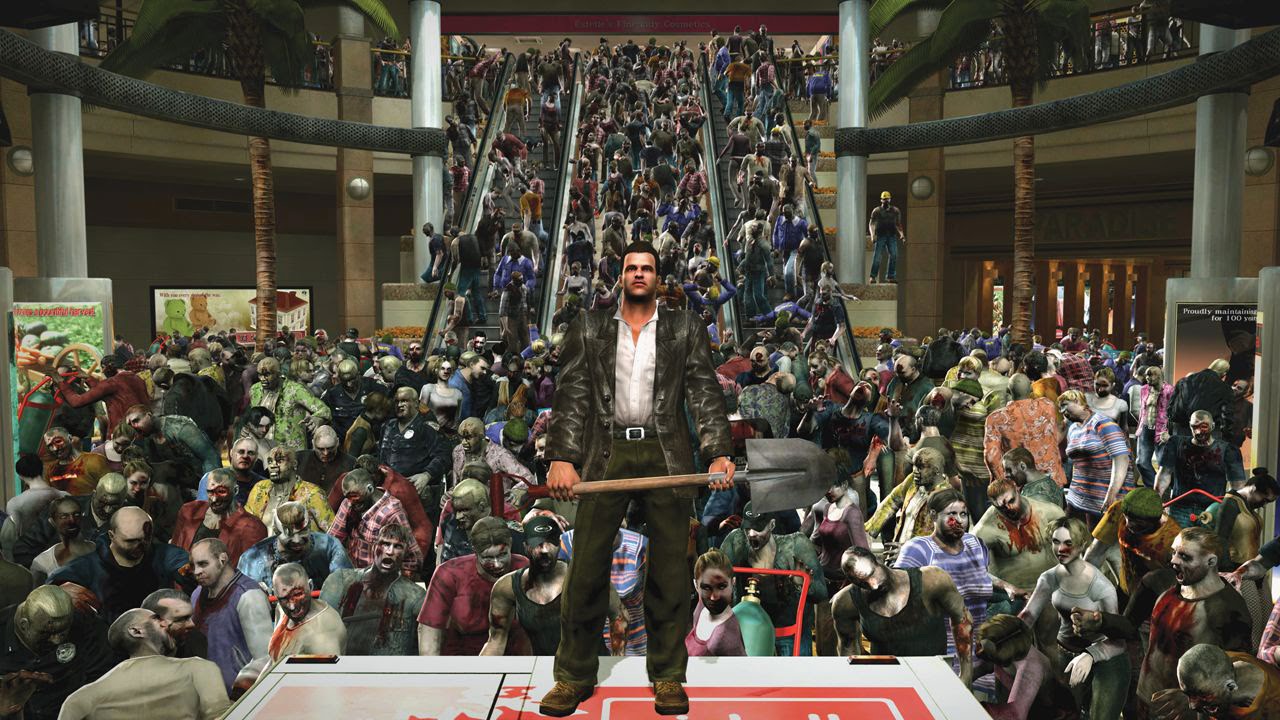

The core conceit in Dead Rising—beyond beating zombies to death with the literal manifestations of consumerism—is a running clock. Frank West, the game’s core character (and an absolute granite slab of a man), has 72 hours before an escape helicopter arrives to solve a mystery about a zombie outbreak in a mall. This mystery snakes and shifts in ways that always keep Frank, and the player by extension, ever on the move. The clock is always ticking, literally. Frank has a watch that the player has to frequently check to make sure they are on track to get everything done in time. With thousands of zombies lurking through the mall—and some evil humans to boot—the scariest thing in Dead Rising turns out to be time itself. You can’t bludgeon time with a golf club or beat it with your fists. It never stops, it is always moving, and it always feels just out of reach.

Video games often let players control every aspect of time—fast-forwarding through it as they see fit with the ticking clock only ever making a rare visit in certain missions or crucial moments. But Dead Rising is built on that ticking clock. Every aspect of the game is inherently tied to and affected by time. Every step is played in tandem to the tick of the clock. The watch on Frank’s wrist is less a watch and more of a shackle that binds him to the heavy and inescapable thing that is time itself. He has 72 hours to solve the mystery of a zombie outbreak, save the survivors in the mall, and then escape via rescue chopper. But things go wrong like they often do in horror games, and horror in general. Timelines go fraught and things come down to the wire. Survivors die, Frank gets set back, he doesn’t make it to some sidequests in time—they expire—and he has but little time to finish certain main missions. This tension is built into the game but it is also up to the player to some extent. I probably spent way too much time messing around, exploring the mall, and just killing zombies with lots of random items in the mall. Through doing so, I missed core side missions and found myself with hardly enough time to make it to some core missions.

That feeling of time rapidly expiring between points A and B is deeply stressful. That stress is built out of the horror trappings of the game, but also out of the baggage we bring to the game in regards to time. Ever just barely made it to a job interview? You know that feeling, Dead Rising knows that you know that feeling, and it ratchets that tension up to 11. Through doing so, every action is both deliberate and tinged with that feeling we all know from horror films where something is right on the main character’s trail—just nipping at their heels and barely out of reach.

Frank West is a broad man who can hold his own against hundreds of zombies and humans turned evil, but Frank’s hands cannot pummel what turns out to be his cruelest enemy in the game—time. It is always at his heels and it hangs over him and the player like a shroud. When time becomes a game mechanic that cannot be fundamentally changed, then the player can either embrace the flow of it or constantly try and exploit it. And that is the core tension in Dead Rising. The zombies are merely circumstantial, and the true horror born out of this wrestling with time is more existential than any sort of “in the moment” terror. There are no true jump scares or stomach-drop moments unless one forgets about the time mechanic completely and then realizes too little too late that they’ve thoroughly screwed themselves over. Thus this existential fear burrows rather than occurs again and again and again. It is not stop-and-go. The existential threat of time itself is always there, no matter where Frank West is. Even the safe rooms cannot save him from time; it is that invisible following beast that one can never outrun yet is rarely caught by. Time becomes a vengeful parasite, an enemy even, that Frank (and the player) simply have to make peace with.

When we make peace with the fact that we cannot control time, a certain serenity might begin to rear its head. But that peace is often shattered when external forces render time an enemy yet again. Things might be going well and then Frank gets stuck fighting a boss. Time continues to pass. That old familiar stress sets back in. The boss zombie bleeds and dies and the area becomes awash in its viscera, but time is right there just above it all and out of reach. The clock ticks a doomful tick and it will do so forever.

Editorials

‘A Haunted House’ and the Death of the Horror Spoof Movie

Due to a complex series of anthropological mishaps, the Wayans Brothers are a huge deal in Brazil. Around these parts, White Chicks is considered a national treasure by a lot of people, so it stands to reason that Brazilian audiences would continue to accompany the Wayans’ comedic output long after North America had stopped taking them seriously as comedic titans.

This is the only reason why I originally watched Michael Tiddes and Marlon Wayans’ 2013 horror spoof A Haunted House – appropriately known as “Paranormal Inactivity” in South America – despite having abandoned this kind of movie shortly after the excellent Scary Movie 3. However, to my complete and utter amazement, I found myself mostly enjoying this unhinged parody of Found Footage films almost as much as the iconic spoofs that spear-headed the genre during the 2000s. And with Paramount having recently announced a reboot of the Scary Movie franchise, I think this is the perfect time to revisit the divisive humor of A Haunted House and maybe figure out why this kind of film hasn’t been popular in a long time.

Before we had memes and internet personalities to make fun of movie tropes for free on the internet, parody movies had been entertaining audiences with meta-humor since the very dawn of cinema. And since the genre attracted large audiences without the need for a serious budget, it made sense for studios to encourage parodies of their own productions – which is precisely what happened with Miramax when they commissioned a parody of the Scream franchise, the original Scary Movie.

The unprecedented success of the spoof (especially overseas) led to a series of sequels, spin-offs and rip-offs that came along throughout the 2000s. While some of these were still quite funny (I have a soft spot for 2008’s Superhero Movie), they ended up flooding the market much like the Guitar Hero games that plagued video game stores during that same timeframe.

You could really confuse someone by editing this scene into Paranormal Activity.

Of course, that didn’t stop Tiddes and Marlon Wayans from wanting to make another spoof meant to lampoon a sub-genre that had been mostly overlooked by the Scary Movie series – namely the second wave of Found Footage films inspired by Paranormal Activity. Wayans actually had an easier time than usual funding the picture due to the project’s Found Footage presentation, with the format allowing for a lower budget without compromising box office appeal.

In the finished film, we’re presented with supposedly real footage recovered from the home of Malcom Johnson (Wayans). The recordings themselves depict a series of unexplainable events that begin to plague his home when Kisha Davis (Essence Atkins) decides to move in, with the couple slowly realizing that the difficulties of a shared life are no match for demonic shenanigans.

In practice, this means that viewers are subjected to a series of familiar scares subverted by wacky hijinks, with the flick featuring everything from a humorous recreation of the iconic fan-camera from Paranormal Activity 3 to bizarre dance numbers replacing Katy’s late-night trances from Oren Peli’s original movie.

Your enjoyment of these antics will obviously depend on how accepting you are of Wayans’ patented brand of crass comedy. From advanced potty humor to some exaggerated racial commentary – including a clever moment where Malcom actually attempts to move out of the titular haunted house because he’s not white enough to deal with the haunting – it’s not all that surprising that the flick wound up with a 10% rating on Rotten Tomatoes despite making a killing at the box office.

However, while this isn’t my preferred kind of humor, I think the inherent limitations of Found Footage ended up curtailing the usual excesses present in this kind of parody, with the filmmakers being forced to focus on character-based comedy and a smaller scale story. This is why I mostly appreciate the love-hate rapport between Kisha and Malcom even if it wouldn’t translate to a healthy relationship in real life.

Of course, the jokes themselves can also be pretty entertaining on their own, with cartoony gags like the ghost getting high with the protagonists (complete with smoke-filled invisible lungs) and a series of silly The Exorcist homages towards the end of the movie. The major issue here is that these legitimately funny and genre-specific jokes are often accompanied by repetitive attempts at low-brow humor that you could find in any other cheap comedy.

Not a good idea.

Not only are some of these painfully drawn out “jokes” incredibly unfunny, but they can also be remarkably offensive in some cases. There are some pretty insensitive allusions to sexual assault here, as well as a collection of secondary characters defined by negative racial stereotypes (even though I chuckled heartily when the Latina maid was revealed to have been faking her poor English the entire time).

Cinephiles often claim that increasingly sloppy writing led to audiences giving up on spoof movies, but the fact is that many of the more beloved examples of the genre contain some of the same issues as later films like A Haunted House – it’s just that we as an audience have (mostly) grown up and are now demanding more from our comedy. However, this isn’t the case everywhere, as – much like the Elves from Lord of the Rings – spoof movies never really died, they simply diminished.

A Haunted House made so much money that they immediately started working on a second one that released the following year (to even worse reviews), and the same team would later collaborate once again on yet another spoof, 50 Shades of Black. This kind of film clearly still exists and still makes a lot of money (especially here in Brazil), they just don’t have the same cultural impact that they used to in a pre-social-media-humor world.

At the end of the day, A Haunted House is no comedic masterpiece, failing to live up to the laugh-out-loud thrills of films like Scary Movie 3, but it’s also not the trainwreck that most critics made it out to be back in 2013. Comedy is extremely subjective, and while the raunchy humor behind this flick definitely isn’t for everyone, I still think that this satirical romp is mostly harmless fun that might entertain Found Footage fans that don’t take themselves too seriously.

You must be logged in to post a comment.