Editorials

[‘Aliens’ 30th Anniversary] The One Decision That Makes ‘Aliens’ a Perfect Sequel

Movie sequels of any genre are generally difficult to write, but that’s especially the case with horror. In the original film, a group of characters found themselves in some crazy, life-threatening situation, and by the end, one or two were somehow able to make it out alive. They are probably lead to safety by the time the credits roll, and that’s about it. There’s nothing left open, and the scenario was so preposterous that it’s unlikely the survivors would ever encounter it again. Yet by returning to theaters for a sequel, audiences are clearly hoping for more of the same, so how the hell does a filmmaker set that in motion?

Though it verges into science-fiction territory, the original Alien has quite a bit in common with horror, in particular when it comes to the third act. Ripley, our final girl, escapes the terror of the Xenomorph, defeats it, and emerges victorious. She goes into stasis as the ship apparently heads home, and that’s all, folks. We don’t leave feeling we need to have the story continued, and once Ripley makes it back to Earth, we would assume she’d retire to an island somewhere and never set foot in space again.

This presents James Cameron with a tremendous problem as he begins work on a sequel. Audiences obviously want Ripley back, as Sigourney Weaver was a significant reason the first movie was so great, and they clearly want her to kick some more Xenomorph ass. Imagine for a moment that Aliens does not exist and you’re in Cameron’s shoes in the early 1980s trying to figure out a way to extend Ridley Scott’s storyline. What do you do?

The dilemma is quite frequently seen in horror, a genre in which sequels are as common as dirt, but Cameron’s solution demonstrates exactly why he’s a master filmmaker and why Aliens is a perfect sequel, whereas other similar part-twos are relegated to the straight-to-DVD bin. In fact, his movie provides a blueprint for modern horror directors attempting to write sequels to seemingly sequel-proof movies.

Aliens opens with Ripley floating in space just where we left her before she is rescued and taken aboard a Weyland-Yutani Corporation ship. Instantly, Cameron decides to show some of the consequences of Ripley’s victory at the end of Alien, revealing that it wasn’t exactly a riding-off-into-the-sunset type deal. Aboard the ship, Ripley receives a shock when she is told that she has been in hypersleep for quite a bit longer than expected: 57 years. Not only that, but she is suffering from severe PTSD as a result of her experience with the Xenomorph, having a horrifying dream of one of the creatures bursting out of her chest. Right away we see that she may have killed the alien, but that doesn’t mean she got away scot-free.

Moments later, we pick up with Ripley sitting on a bench looking out into the forest longingly. As the camera pans, it is revealed that this lush environment was merely part of a computer screen, and immediately Ripley is torn from her dreamlike state and pulled back into the harsh reality from which she has not escaped quite yet. We can feel her eagerness to return home and let her wounds finally heal, which makes the decision to come in a few moments all the more taxing.

Burke arrives and informs Ripley that her daughter, Amanda, who was 11 years old when Ripley left Earth, died at the age of 66 while Ripley was in hypersleep. When Ripley left for her original mission, she had never considered the possibility of not being there for Amanda’s entire life, but now, she holds in her hand a photo of her daughter as an old woman, reflecting on all the time she missed as a direct result of the Xenomorph attack. “I promised her that I would be home for her birthday,” Ripley finally lets out, and in one line, Cameron hits us with the same gut punch Christopher Nolan would later utilize in Interstellar. Ripley was concerned about missing one of Amanda’s birthdays, but now, she has missed them all. (This happens in the extended edition, at least, and it’s quite baffling that this detail was left out of the original cut.)

She is soon told that LV-426, the planet on which the Nostromo first encountered their Xenomorph, is now home to a colony of humans including many kids. Ripley is clearly haunted by the fact that she was not able to be there for Amanda, who she abandoned and let slip away. But now, being the only person who fully understands the threat posed by the Xenomorphs, she has the chance to save other young girls and boys, doing for them what she couldn’t do for her own child. This, in combination with the fact that she is being continuously haunted by the Xenomorphs and feels she must finish what she started, inspires Ripley to reluctantly travel to LV-426.

It obviously is not an easy choice for her to make. When Burke first brings up the idea, she is understandably dismissive, just as audiences may have been dismissive of the idea of producing a sequel to Alien and forcing Ripley to go through even more terror. But in these masterful opening minutes, Cameron gets across the profound loss Ripley has suffered, the pain she continues to experience, and the fact that she now has little left tying her to Earth anyway. He has convinced us that this movie was worth making, something few horror sequels actually bother doing.

Cameron could have easily come up with some phony scenario in which Ripley would have no choice but to fight more Xenomorphs; perhaps her ship crashes onto LV-426 and she must fight her way to freedom. But by rooting the thrust of Aliens in Ripley’s character and giving her a choice of whether to run or to fight, everything that happens in the ensuing hours means so much more, and we truly care about her making it out alive again. If the scenario was not believable, and if Ripley had no new conflict to overcome, we would tune out. Here, the drama is rooted in the main character’s desires, giving her both a physical problem – fighting the Xenomorphs – and a non-physical problem – learning to accept the loss of her daughter.

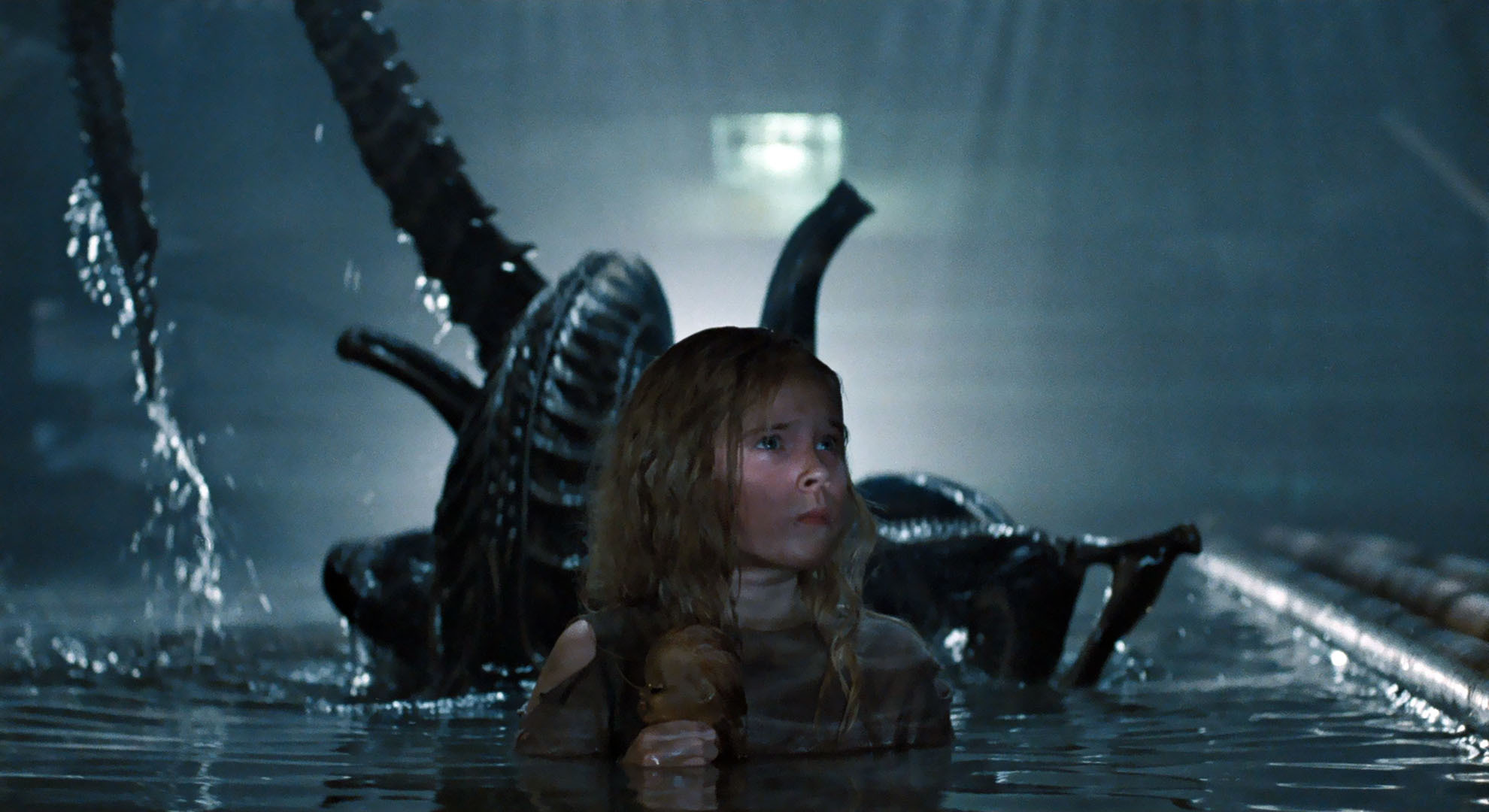

Later in the movie, Ripley forms a connection with a little girl named Newt, who clearly reminds her of Amanda. In Newt, Ripley sees an opportunity to connect with and save someone in the way she previously failed to do, and so Ripley’s journey in the movie is completely distinct from her journey in the original Alien. She is not merely helping a bunch of random civilians out of the goodness of her heart; she’s also coping with her grief and learning to love again, both to love Newt and to love herself, which makes Aliens a fresh emotional arc for Ripley. Compare this to the vast majority of horror sequels, where the character’s storyline is merely repeated a second time and little new ground is covered.

Take the scene where Ripley and Newt share a conversation and Ripley opens up about the fact that she used to have a daughter. She says to Newt, “I’m not gonna leave you Newt. I mean that. That’s a promise.” We can imagine how hard these words are for Ripley to get out, given her anger at herself for leaving Amanda and not fulfilling her promise to be back for her birthday. From here on out, after Ripley makes her promise to Newt, even more important than Ripley’s own survival is her ability to ensure Newt’s safety.

And that’s why Cameron so brilliantly makes the final setpiece not about the safety of Ripley – which would be a retread of Alien – but about the safety of Newt. When Newt has been snatched away by the Xenomorph, the rest of the crew believes that trying to rescue her is a lost cause, but Ripley can’t live with herself if she abandons another young girl. She has to do this. “She’s alive,” Ripley says. “There’s still time.” Being out of time is exactly what ripped Amanda away from her, but she won’t let that happen again.

Compare all of this complexity to other sequels involving a character who previously escaped a deadly environment returning for more. In Jurassic Park III, which is essentially a slasher film with dinosaurs, the screenwriters must figure out a way that Alan Grant would go back to Isla Nublar, even though it was pretty clear by the end of Jurassic Park that there is no way in hell he would ever do so. If Joe Johnston were to take a similar approach as James Cameron did with Aliens, he would give Alan Grant some sort of unfinished business and a desire that is tied up with the adventure so that traveling back to Jurassic Park is necessary in completing his character’s journey.

Is that what happens? Nope. The way that Johnston sets the pieces back in play is hilariously lazy. Alan Grant is approached about returning to Isla Nublar, and he says no. But then he’s offered a lot of money, so he says yes. That’s basically it. He is assured the plane he’s on will only fly above the island, but then in an unexpected turn of events that Grant should have totally expected, he wakes up on Isla Sorna like the dudes in The Hangover II, going through the exact same adventure again for some stupid reason.

It’s so clear how unneeded the whole story is. Alan Grant’s arc was complete in Jurassic Park, and this follow-up does nothing to convince us he has more work to do. Johnston simply throws Grant back on the island, and when Grant flies away in a helicopter for the second time at the conclusion of the movie, we don’t feel as if he’s a substantially different person than when we left him in Jurassic Park. All of this happened because Universal wanted to make some money off a sequel.

The same is true of The Descent Part II. Sarah has escaped the cave, but Jon Harris needs to get her back in for this sequel, and so the characters essentially drag her back in kicking in screaming. The journey does not involve her making any sort of decision, and there’s no unfinished business or justification for why we’re doing all of this again. It’s the problem so many horror films run into unless they focus on an entirely new set of characters. It’s not merely about finding a way to literally continue the plot; it’s about getting around the fact that the character’s arc was already resolved, and so now they must be given another one that is totally distinct. James Cameron does this with Aliens, but with horror sequels, barely anyone else bothers.

Much attention is paid to the fact that Aliens shifts genres a bit, going in the direction of action-adventure while the first film was focused on horror. That’s true, but it’s not the real brilliance of the picture. The reason it’s so great is that James Cameron takes a movie that clearly did not need a sequel and, by the end, makes us feel that a sequel was in fact incredibly necessary.

As the film closes, Ripley flies away from LV-426 with a much greater sense of accomplishment. While last time around she simply escaped an alien attack but felt a lingering sense of unfinished business, this time, she went back in on her own volition, stood up to these creatures that have been plaguing her nightmares, and declared that she is not afraid. She holds Newt in her arms, learning to trust herself with another life again, and Newt tells Ripley, “I knew you’d come back.” After the tremendous guilt of having gone off to space and having left her child, Newt has filled a void in Ripley’s life that she thought would forever remain vacant.

In short, Aliens works because Cameron understands that audiences will roll their eyes if a sequel is based on some phony plot where the lead character is to thrust back into the identical situation for no discernible reason. The film must give its protagonist the decision of whether to run back into danger, and it should present them with a brand new problem that has arisen as a direct result of the previous movie’s climax. Aliens solves the classic dilemma of figuring out how to return a main character to deadly circumstances while keeping the audience on board, and for that reason, it may be the perfect horror sequel.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.