Interviews

“Paperbacks From Hell”: Interview with Author Grady Hendrix

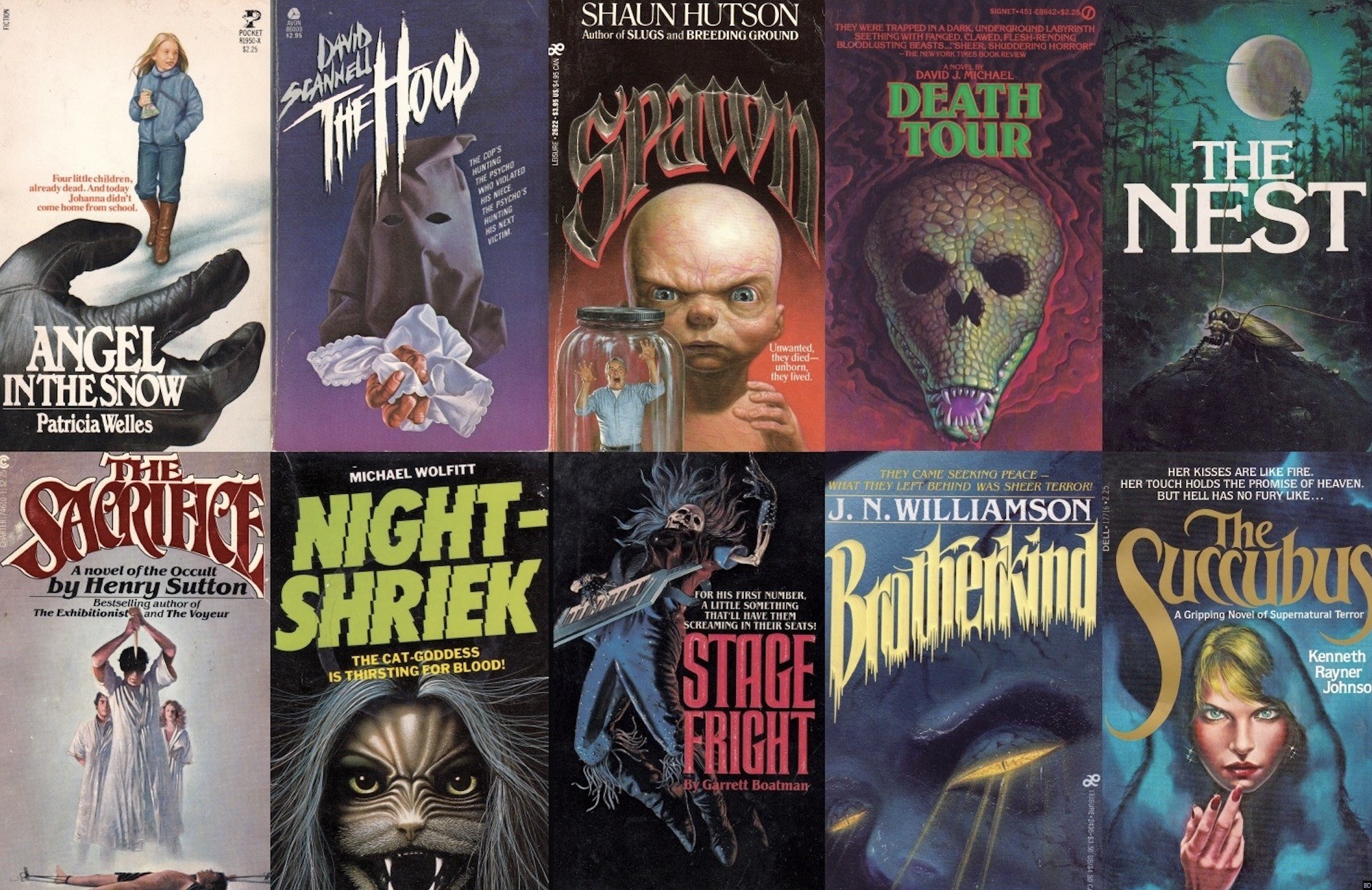

With a significant amount of seriousness, satire, and his signature carnival barker delivery, Grady Hendrix has delivered one of those rare books that will be a permanent fixture on your shelves. Paperbacks From Hell is a whirlwind history of devilish children, panicked suburbanites, angry animals, insidious doctors, uncontrollable contagions, and, sometimes, teddy bears with axes. A lovingly created and fully illustrated tome dedicated to the rise and fall of the infamous paperback horror boom in the 1970s and ‘80s. I had the pleasure of speaking with Grady about this unique project.

Jonathan Lees: If you could give yourself a nice cover blurb for Paperbacks From Hell, what would it be?

Grady Hendrix: The one I would want would say, “This is the best book in the world!” – Stephen King. That’s what I really want but I don’t think that’s going to happen. The pitch for Paperbacks, the logline, is basically a history of the paperback horror boom of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Those books were everywhere when I was growing up then they just disappeared. Like, what the hell happened to them? That was as interesting a story as what they were.

JL: When you were doing research for the book and you discovered Will Errickson’s amazing blog, Too Much Horror Fiction, you mentioned you “blacked out”. Considering how much material you’ve read and researched, have you ever truly regained consciousness?

GH: No. Well, I guess I regained consciousness to write this book. I didn’t have any plan when I started buying these books. I just saw how cheap they were and started fumbling around buying stuff mostly based on Will’s recommendations on his blog. There’s no way to know, when you’re confronted with these giant paperback swap shop shelves, what’s trash and what’s treasure. I haven’t heard of most of these authors or haven’t at the time. Bestsellers come and go and it’s kind of sobering when you realize you can sell a ton of books and can be completely forgotten except maybe as some half-remembered “Oh that guy”. So I really just started buying unconsciously because also… I’m a film guy first. With film people there’s this real tradition of going out into the wilderness and watching stuff and looking for really obscure gems to bring back and be like “Oh my god, have you seen this?”.

JL: Sure! That was an art. Growing up, digging for all those VHS tapes… I remember combing mom and pop shops for Icy Breasts and Joe D’Amato’s Buried Alive in the big box…

GH: Exactly. Import tapes and stuff like that. I know people are collectors but there isn’t this tradition in books like let’s go out and find weird stuff that’s old and out-of-print and talk about it. There’s a huge book community on YouTube and Tumblr but they’re concerned about new stuff. There’s not that kind of underground that I can find with books.

JL: It’s hard to find enough people that might have read The Fog by James Herbert or even something more obscure.

GH: Yeah, I think it is because reading takes a long time and because it’s a private experience… you can watch a movie with other people, you read a book on your own. I also think that books, unlike movies, have this sort of phony-baloney- highbrow patina over them. There’s this idea that reading books is really good and worthwhile and nutritious. Which is great when I was a kid. As long as I was reading my parents didn’t care what I was reading. Because they’re books it must be good for you. I read some really hair-raisingly inappropriate stuff growing up. My parents didn’t even notice.

JL: You could get away with it!

GH: Books do have this sort of stuffy, puritanical, self-improvement angle that movies don’t. Movies are trash.

JL: (laughs) Yes!

GH: Movies that aren’t trash are exceptions. Like people are still outraged that MoMA has movies in its collection.

JL: In an overview of all this immense material that you cover in Paperbacks From Hell you stated, “Most of these [books] respect no rules except one: Always be interesting.” Do you still think that’s the case after reading all of these?

GH: I think everyone wants to be interesting. The stuff was market-driven so people knew that their readers had short attention spans and they wanted some sex and some violence and some weird stuff they weren’t getting anywhere else. There’s some real D.O.A. stuff in there. Like William Johnstone, who wrote Toy Cemetery, and J.N. Williamson, who wrote god knows how many books. They both are bad writers but Johnstone is really interesting because he’s constantly throwing new stuff at readers. He has real obsessions. Like anal sex and devil cults.

JL: (laughs) You mention that in the ‘60s, horror was not a term used to sell paperbacks… it was a term to be avoided. Can you let us know why and how this disdain for horror branding resurfaced around the mid-nineties?

GH: There are books that I find from time to time in the ’50s and ‘60s that have the word horror on the cover as part of the blurb but almost exclusively it’s either a Robert Bloch book or Richard Matheson. It just wasn’t in usage and, of course, when you have these big hits come along like Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist and The Other suddenly horror becomes a marketing category. And then in the late ‘80s after The Silence of the Lambs and especially early ‘90s there was already this huge glut. I was talking to someone who was in a Barnes & Noble in the late ‘80s and they said there were so many horror and genre paperbacks out there the staff had just given up on shelving them. They were just piling them up in a grocery cart at the end of one of the aisles.

You had this early ‘90s effect where there was too much product in the market, too little quality control, too many manuscripts being rushed to print and the books were getting super gory and, as a side effect, they were so misogynistic. You could have made a case that in 1992, with few exceptions, horror was simply a category of women getting raped and murdered. Basically, people just rejected it. Horror books started to bomb hard. Since The Silence of the Lambs was such a huge hit everyone was rebranding horror novels as thrillers. Someone told me they had a manuscript where they simply removed the word vampire from it, exchanged it with serial killer and resold it. That made it marketable. What it gave people the impression of is that horror novels, or horror, was cheap. It was gross and offensive. That really stuck with horror for a long time. It still does to some extent.

JL: Oh, it totally does. You see that mirror, once again, in film. People just relate the ‘80s slashers to the entire horror genre. I think it’s changing now when books like Paul Tremblay’s A Head Full of Ghosts and movies like The Babadook or It Follows are catching the popular eye.

GH: Mark Danielwski, who did House of Leaves, Chuck Palahniuk, Paul Tremblay, John Langan, and Laird Barron, they’re all sort of sneaking horror back into literary fiction and bringing literary fiction back into horror. I really think that those guys are doing this subversive and very quiet horror.

JL: I love that no matter how much you explore the sub-genres and the themes created within this period you give a great amount of space in the book to what is arguably the most important marketing tool for all these paperback horrors and that’s the cover art. I judge books by their cover. My grandmother started me on all this. I remember her paperback copy of The Legacy. Why she had that I have no idea. Also, Flowers in the Attic and V.C. Andrews die-cut covers I was obsessed with. How important were the covers and what did you learn from all these artists who went unnoticed and ignored for all the brilliant work they did?

GH: The covers were super important for two reasons. One was that as horror took off as a genre… yes, you had Stephen King and V.C. Andrews and Anne Rice… you had names people knew but you mostly had a lot of authors that no one knew. For every author that was able to build a brand around their name like Peter Straub or John Saul you had dozens of authors that no one cared about. So publishers realized their best tool was the covers and on the top of that you had places like Zebra who were publishing horror they couldn’t afford good manuscripts or good authors and they knew the cover was their best shot. They were really working hand in hand with the art director who would give them sketches and direction and all that. The art directors were really kings of the publishing houses. There were a couple of these big dogs, especially Milton Charles, at, I believe, Pocket, at the time really believed that photography was not the way to go. You had to have a painted cover because you wanted it to look realistic but you didn’t want them to be models. He thought that showing models as characters in the book would turn off readers because they wouldn’t be able to imagine themselves as the hero of the book. Charles was really bummed out because there weren’t enough realist painters out there so he went off and taught classes and basically trained a whole new generation of realist illustrators. What happened with these guys was they came along and did these beautifully painted covers but in the ‘90s a lot of them fled for romance fiction because that was sort of the last bastion of fun, painted covers but also as digital came in there was this movement to eliminate the brush stroke. To have it all digitally smooth and plastic looking. To almost look like a photograph. Also, covers started getting abstract again so all these painters went over to romance and children’s books which are still heavily illustrated. Digital helped kill it but the trend back towards abstract and away from the brushstroke.

JL: What’s crazy to me is how careless some of the industry is right now with their covers. I mean, you have someone, even a giant like Stephen King, who is going to make money no matter whatever reprint you put out there but some of his reprint covers… They are garbage. So terrible.

GH: It’s funny. A lot of King’s paperbacks… I’m kind of surprised at how bad the covers are. I know some people that have done some good ones so there are still art directors who get it and push for this stuff but one thing that’s really happened too is that marketing and sales departments have kind of taken over. They call the shots the art directors used to call. And one of the reasons that happened was because of digital techniques. In the past sometimes the marketing or sales people would show up at a meeting and they would bring some images like what they wanted and it would be something from a magazine or a photograph they liked or a painting or something but with digital they were roughing up their own covers. Then the art director just becomes a pair of hands for the salespeople. Now people just talk about endless meetings with all these different departments where everyone has input.

JL: I think that seems to be an industry standard in media in general. It’s kind of sad but some people escape it thankfully. So in relation, let me know the three covers that really knocked you out.

GH: One of my favorite covers is Killer by Peter Tonkin. It’s a Ken Barr cover and it’s great. There’s a killer whale and people are throwing dynamite at it. Just this fabulously old-school painted cover. Lisa Falkenstern’s cover. The one she did for Tricycle. She’s so iconic, the work she did. And then I’d say almost anything by Richard Newton. he did a cover for Guardian Angels and he did a cover for William Johnstone’s Sandman. It’s like a skeleton sitting on the moon, holding a teddy bear, and it’s wearing slippers. I love that the skeleton’s feet are cold. And you’d have to mention a Jill Bauman doll painting for Garden of Evil or When Darkness Loves Us or The Kill by Alan Ryan. Her dolls are everywhere and she does such an amazing job with them. Actually, someone I don’t give any time to in the book who really deserves more attention is William Teason. He did a lot of covers for anyone who who would ask him to basically but he did a great one for a book called Wild Violets and Blood Sisters. He’s heavy on the skeleton covers but people really talk about Teason in the same breath as Norman Rockwell or Andrew Wyeth as one of the great American illustrators. Towards the end, horror was where the work was so he did all these covers for Zebra. It’s criminal that he’s not held in the same regard as someone like Wyeth or Rockwell.

JL: There are some great questions that arise in your book and some life lessons… like “How do I know if the man I’m dating is the devil?” and “How can I possibly stop my child from murdering strangers?”

GH: It’s important.

JL: (laughs) Yes. What did you learn most while working on Paperbacks that you can apply to your own writing and we should mention that you recently wrote My Best Friend’s Exorcism and Horrorstor…

GH: I would say three lessons from this are… One: Everyone’s going to be forgotten. It doesn’t matter how many units you sell. Twenty years after he dies people are going to be like, “Stephen King… didn’t he write The Shining?”

JL: (making noises that mimic either a heart attack or seizure)

GH: The other lesson I learned is just how to keep things moving. These books are really designed to drag you through the narrative and they use so many tricks for that. I’ve always liked Elmore Leonard’s Ten Rules for Writing. One of them is “leave out the part that people skip”. Because I read so many of these books I was like “Ok that description’s nice but I’m skimming”. It really gave me an idea on what is skippable in a book and what you need to hack it down to like the bones and the muscle. And the third thing I learned, honestly, no one wants to read about an animal getting killed. Every time it happened in one of these books, and they killed animals left, right, and center, I’d have such an outsized reaction to it. You realize when writing a book that the most sympathetic character on the page is an animal because they just shut up and they don’t do anything that makes people think they’re an asshole.

JL: The amount of material you read for this… do you just have an insane memory and this is recalling from decades of reading these paperbacks?

GH: I keep a log of everything I read because otherwise I just forget. When I looked at the log for this book, in the period just for this book, I read about two hundred and thirty six books.

JL: Oh my god.

GH: I would say for about three months at the beginning of this project because I was talking to Will [Ericsson] about the structure of the book, my full-time job was reading. On an average day I could get through about four books. On a bad day I could do one or two. And on a day when I really couldn’t do anything else I could get through six. It was really helpful that I’d read the same books, like reading all the killer child books at once, you start to learn what the signposts are. Or the medical thrillers you’re like “Ok this is the part where the doctor is going to explain the theory of in-vitro fertilization for twenty pages. Skim. Skim. Skim. Skim.” You could read fast because you knew where the benchmarks were.

JL: Of all the sub-genres, which ended up being your favorite?

GH: One of the weird things that’s happened doing the book is how many of the sub-genres that have disappeared. There are no more Native American curse books or pregnancy fear books but for a chunk of time in the ’80s there were dozens published every year. You get this feeling that there will always be books about doctors stealing women’s babies and then… they just go away. You can’t count on anything.

Ultimately what wound up being my favorite was the “Animals Attack” books. Animals Attack or Killer Kids, I think. In a lot of Killer Kids books the author will pul their punches a bit because it’s like… kids in danger. The ones that don’t pull their punches are great. Animal Attack books though, very early, started scraping the bottom of what animals could attack and you start getting two different books about killer jellyfish, a couple books about killer rabbits. They were just getting the most absurd animals and authors really pushed it. There’s some great rabies scare novels from the UK. There’s one where it’s like killer caterpillars are attacking England and they discover that these three foot long iguanas can eat the caterpillars so they unleash them in England and the epilogue is these characters sitting around in their house that’s overrun by three foot long iguanas being like “Hm maybe that wasn’t such a good idea”. I think killer animals bring out the best in a lot of authors.

JL: You cover so many people that have changed the industry and written some amazing work that may have been hidden behind lurid covers. If you wanted to shine a light on one person you discovered on this journey that really should be just returned to again and again, who is our unsung hero?

GH: I would have to say Ken Greenhall. He only wrote seven books and one of those, which I think is his best book, isn’t even horror but he was a dude who always had a day job as an encyclopedia editor, his books came out from the worst publishers, they were given the worst covers… even his own agent fired him at some point in his life and was like, “You’re too old. Bye.” He only ever had one book come out in hardcover which was his last one, the historical novel called Lenoir but his writing is beautiful. He really is an heir to Shirley Jackson. His prose has this really precise, chilly, stark quality to it that she had.

He’s really good at stripping a line down until his sentences go in these unexpected directions and every single one of his books is told from the point-of-view of his main character which means he’s written really convincing books from the point-of-view of a fourteen year old girl, a killer dog, from the point-of-view of a really rich guy who doesn’t want to be bothered by anyone and sells cognac, from the point-of-view of a 16th Century freed African slave. Every one of those voices he writes in is just so compelling and so authentic and he’s completely forgotten. Valencourt has started bringing some of his books back in print like Hellhound, Elizabeth, and Child Brave and those are his three best horror novels.

JL: What we’re seeing right now could be called a resurgence in horror fiction, You’re contributing to it. There is a lot of brilliant material out there. What one thing could you tell us that we can learn from this period especially the ebb and flow of the Leisure shutdown and the horror crash in the 90s…

GH: Everything happens in cycles. I think horror is coming back… because horror books don’t make money… the people doing it really want to write horror now not because they’re chasing a fad and eventually people will see money being made in horror [publishing] and they’ll chase the fad and we’ll all go bust again. I guess that’s the lesson from this which is to me the people who wrote out of love, like the people who wrote stuff that is genuinely something they cared about that happened to be horror, like Elizabeth Ingstrom or Bari Wood or Ken Greenhall or even William Johnstone in his own crazy way. They were all pursuing their own personal vision and it happened to be horror and they’re the people who have lasted… well, they’ve been forgotten but they’re the people who are getting rediscovered. The people who just wrote because they wanted to cash in… J.N. Williamson, John Coyne and John Saul, I mean I like those guys but they wanted to sell books and horror is what was selling so they decided to write horror. They don’t hold up quite as well because it’s not personal. This stuff is always going to boom and bust but it booms when it’s not making any money and the people doing it are doing it for sick, sad, personal reasons.

JL: (Laughs) I’m hoping that everyone who reads this runs to their local mom-and-pop shop and combs the shelves, pulls out something ridiculous and discovers something wonderful.

GH: They’re out there. Just waiting.

Grady Hendrix is also the author of Horrorstor and My Best Friend’s Exorcism available from Quirk Books. He is currently re-reading all of Stephen King’s novels and collections and reporting on them at Tor.com. You can also catch him doing live performances of Paperbacks From Hell nationwide. For more info, visit http://www.gradyhendrix.com

Interviews

“Be Not Afraid”: Andrea Perron Shares the Chilling True Story Behind ‘The Conjuring’ [Interview]

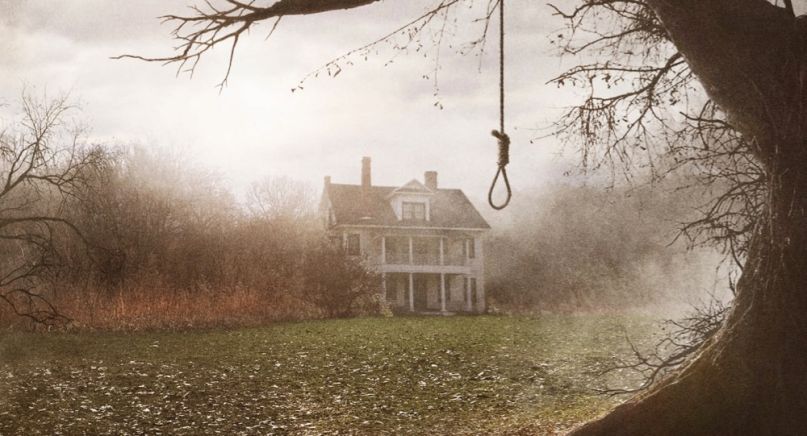

Welcome back to DEAD Time. I hope you left a light on for me because this month we’re going inside The Conjuring house to find out the real story of what happened to Carol and Roger Perron when they moved their five daughters into a house in Burrillville, Rhode Island in the early 1970s.

In 2013, director James Wan unleashed the terrifying horror film The Conjuring, which was based on the case files of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren and told the story of a family tormented by a demonic force after moving into their new home. In real life, the Warrens did investigate the activity in the Perron home, but the story goes a bit differently. You may think you know what really happened inside that house based on the horror movie alone, but you would be mistaken. The true story is much, much scarier.

Bloody Disgusting was delighted to have the opportunity to chat with Andrea Perron, the oldest of the five Perron daughters, who was witness to the paranormal activity in the family’s home. Andrea is a lecturer and the author of the trilogy of books, House of Darkness House of Light, which tells the story of what her family experienced while living in the house in Rhode Island for a decade. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Bloody Disgusting: Your family moved into the old Arnold Estate in 1970, correct? How long after you moved into the house did your family begin to experience unusual activity?

Andrea Perron: We bought the house in December of 1970, but we didn’t move in right away because my mother didn’t want to move during Christmas. My mother found the farm for sale and our family went to the farm a number of times and we loved it and we all felt like it was home to us. It was an original colonial home and a farm and 200 acres of land it was a big deal. My parents paid $72,000 for the house and back in 1970 that was a lot of money. All of the times we visited the house with Mr. Kenyon, who was the owner, none of us remembered having anything strange or otherworldly or mystical happen. We just enjoyed the property and the land, and the place itself was just so incredibly enticing. None of us have any memory of seeing anything strange or weird there until the day we moved in. It was as though the spirits were all just holding their breath [laughs] waiting for us to get there and live there.

The first thing that happened was my father opened up the back of the moving truck and handed me a box. We were in the middle of a snow and sleet and ice event, and the wind was whipping around, and it was freezing cold. I went into the nearest door with the box that was marked kitchen and my mother had already come in with my baby sister April and had gone into the kitchen. April was only five, she was too young to help unpack or help unload boxes, so she just stayed with mom. I walked into the parlor and took a right into the living room and Mr. Kenyon was packing a box of his wife’s china. I stopped and started chatting with him and then I picked up the box and turned to go into the kitchen through the front foyer, and there was a man standing there that I thought was oddly dressed. He seemed like flesh and blood to me to the extent that as I walked past him, I said, “Good morning, sir.” I didn’t see him when I walked into the room, but he was standing in the corner of the door when I picked up the box. So, I walked into the kitchen, and I remember asking my mother who that man was with Mr. Kenyon. Her response was, “There’s nobody with Mr. Kenyon. His son is on the way, but he’s not here yet.” So, I’m sure at the age of twelve, I assumed that a neighbor had stopped by, and my mom didn’t know it.

I went back outside to the moving van and meanwhile, my sister Christine walked in, and she saw him and walked into the kitchen and asked my mom the same question. Mom was busy; she had discovered that Mr. Kenyon had not packed anything in the kitchen. So, Christine asked who the man was. Then my sister Cindy walked through with her box, and she saw him and asked mom about the man that was with Mr. Kenyon and made some comment that he was dressed funny. Then Nancy walked in behind Cindy and said, “Cindy, did you see that man with Mr. Kenyon? I did, but he just disappeared.” That was our introduction to the farm, and it all happened within the first five minutes. Right before he left, Mr. Kenyon asked my father to go for a walk with him. He said to my father, “Roger, for the sake of your family, leave the lights on at night.” My father didn’t know how to interpret that statement. In his mind, Mr. Kenyon was saying that we were moving into a new house with one bathroom on the first floor and the girls would be sleeping upstairs, and that he should leave lights on, so the kids don’t go tumbling down the stairs in the middle of the night. That’s how he interpreted what Mr. Kenyon said to him. Over the first few months we were living there, we were told by various people in the area that there was never a time when it was dark outside that every light in the house would not be on.

BD: I read that you described the house as “a portal cleverly disguised as a farmhouse.” What led you to believe the house was a portal?

AP: It wasn’t just the house, it’s the property. The barn is as active as the house is. And the property is as active as both the house and the barn. There’s an awful lot of elemental activity. There’s tons of extraterrestrial activity there. And I think it has something to do with the fact that the farm is built on top of an ancient river which was lost during the last Ice Age. It’s known as the Lost River of New Hampshire, but it actually runs all the way underground. It’s buried about 700 feet underground. And on certain days when the water is very heightened and rushing, you can actually feel the vibration of it in the land. And you can lay on the stone walls and feel the stones vibrating from the river rushing underneath our feet. And it goes directly underneath the farm, but also there are two creeks or tributaries to the Nipmuc River, which runs right along the bottom of the property just beyond the stone wall that marks the backyard. So, the river is maybe 700 or 800 yards away.

I think it has something to do with all the water that it is surrounded by. Somebody sent me a drone shot of the farm from high enough up that it was probably, the drone was probably at least 3,000 feet. And it was the most interesting photograph that I have ever seen of the farm because from the angle that the shot was taken directly over it, it looks like a pyramid in the middle of a forest.

BD: Do you have an idea of how many spirits or entities you were dealing with in the house?

AP: Well, I can tell you that there were at least a dozen of them that we were very familiar with that we saw over and over and over again. Another interesting thing too is that the, none of us had any fear of this spirit that we saw that first day moving in. It was, it was not that kind of a vibe at all. In fact, he appeared to be very sweet-natured and cheerful, and he was really focused on Mr. Kenyon. But within the first couple of nights that we lived there, my sister Cindy came crawling into bed with me and she was obviously upset. She was only eight years old and asked if she could sleep with me. And I said, “Of course.” Then I pulled back the quilt and she hopped down.

I’m like, “What’s wrong?” And she said that she could hear voices in her room. Well, the upstairs of the house, every door opens into the next bedroom. And we had all of the doors open because the house was cold and that was the way, you know, to keep the heat moving instead of being trapped in one room or the other. And it was a new house to us even though it was 250 years old. And so, we always left the doors open between our bedrooms. And when she came in, she kept saying, “I hear voices. There’s voices in the room and I’m scared and it got louder and louder. I can’t believe you didn’t hear it.” I can’t believe it didn’t wake you up.” And at first, she was at that time sharing a room with Christine. And my sister Christine has a tendency to talk in her sleep from time to time.

So, I think I just assumed that Chris was doing that. And I asked her, and she said, “No, it’s not me.” She said, “It’s a whole bunch of voices and they’re all talking at the same time. And they’re all saying the same thing.” So naturally I asked her what they were saying, and her response was, “There are seven dead soldiers buried in the wall. There are seven dead soldiers buried in the wall” over and over and over. And she said all the voices were what you would describe as monotone, even though she did not use that word. She didn’t know that word at that time. But she said they all sounded the same. Like they were all talking together, and they all had basically the same voice. And they were all saying the same thing at the same time. And they were all around her bed to the point where the floorboards were shaking. The bed was shaking. And she put the pillow over her head to try to muffle the sound. And when it became so loud that she couldn’t tolerate it anymore, that’s when she jumped out of bed and ran into my room and got in bed with me. And about three years ago, the house, I mean, nothing could be buried in the walls of the house because the house is just clapboard with horsehair plaster. That’s it. There’s no insulation. There’s no, you know, there’s some eaves that go up under the roof line. But there’s just, there’s no place that bodies could have ever been stored or hidden.

So, it didn’t make any sense. But over the years other people speculated maybe there’s someone buried out near the retaining wall behind the house or down around the stone walls. And so, the previous owner, not the woman that owns it now, but the previous owners had some people come in with ground penetrating radar. And sure enough, they found seven distinct anomalies under the stone wall at the bottom of the property just before you go into the cow pasture. And because it is illegal to exhume anything in the state of Rhode Island, all they could do is offer the photographs as evidence. But there it is. There are seven distinct images that are buried just behind the stone wall on the side of the cow pasture. And that’s where they found whatever they found. But when you consider that that house was completed as it stands now in 1736, the property was originally deeded in 1680. And the house was finished as it is now 40 years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. And so, it really is truly an original colonial home. And it survived the Revolutionary War.

It survived the door rebellion. The King Phillips War, the Civil War. And at the time of the Civil War, the owners, and it was all through marriage. It was eight generations of one extended family that built and then lived in the South for hundreds of years. And we were the first outsiders. We have absolutely no familial attachment to the Richardson family or the Arnold family. And that house was passed through marriage because at that time women were not allowed to own property. So, through marriage it became the Arnold estate, but it actually is the Richardson Arnold homestead.

The Real ‘Conjuring’ House – Photo Credit: Visit Rhode Island

BD: At what point did Ed and Lorraine Warren become involved? There were a few things I read that made it sound like they just showed up at your house because they’d heard about the case.

AP: Yes, they really did. They just showed up at our house. Just one day they just showed up.

BD: So, your family had no idea they were coming?

AP: Well, it’s actually a little bit more complicated than that. We’d already been there for about two and a half years. A group of college students came to the house. Keith Johnson and his twin brother, and some of their friends, were paranormal investigators. And Keith said that my mother had called him and asked him to come check the house out. And my mother said, “I never called anybody.” I never told anybody other than our closest friends about the activity in the house.” Our attorney, Sam, knew. Our babysitter, Kathy, knew. And my mother’s friend, Barbara, knew. And she can’t remember anybody else that she ever said a word to about it. It was a very taboo subject back then. And, yeah, nobody wanted to open Pandora’s box. It was way more than a can of worms. It was just not something that people would talk about except for some of my peers at school, kids that had grown up in that town and knew the reputation of the house, which we were never warned about before we moved in. But, you know, I guess the best way to look at this is that the college students that came, we will never know why they showed up. Keith said my mother called him.

My mother said, “I never called anybody.” But there was some reason, and this is a spirit thing. There is some reason that he was drawn to that house and brought his team and had such extraordinary experiences on the one afternoon that they spent there that he sought out. Ed and Lorraine Warren, he and his team sought them out. They were speaking. His team was from Rhode Island College, and the Warrens were doing a lecture in the fall of that year at the University of Rhode Island. And they told the Warrens about our predicament and where we lived and who we were. The Warrens came the night before Halloween in 1973. It was either the night before Halloween or the night after Halloween. When they showed up at the door, my mother let them in the house. It was freezing out and she offered them a cup of coffee and presumed that they were lost because the farm is very remote. And then they identified themselves. My mother had absolutely no idea who they were. She had never heard their names before. And Mrs. Warren walked over to our old black stove in the kitchen, and she put her hand over her eyes and her other hand on the corner of the stove and became very quiet. And she said, “I sense a malignant entity in this house. Her name is Bathsheba.” Now, Mrs. Warren knew absolutely nothing about the history of the house or the area. Nothing. And she plucked that name out of thin air.

Bathsheba Sherman never lived in that house. She lived at the Sherman farm, which was about a mile away. There were only a few homesteads in the area at that time. She was born in 1812 and she died in 1885. And there were stories that she was in that house and had an infant in her care and that the baby died. The autopsy revealed that a needle had been impaled at the base of its skull and it was ruled that the baby’s death was from convulsions. My mother only found one article about it and it was stored in the archives of Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. She read about an inquest in the town of Burillville, Rhode Island. So, there was apparently a hearing in the neighboring town of Gloucester. And apparently there was an inquest and Bathsheba was questioned by a judge about her involvement with the death of the child. And apparently, she was very convincing that she had absolutely nothing to do with it. So it never went to a jury. There was never a formal indictment. It was let go and she was dismissed from the inquest. But in the court of public opinion, this young woman who had just married Judson Sherman was tried and convicted in the court of public opinion. And there were all kinds of accusations and innuendos and rumors that circulated around her for years and years, all the years of her life, that she had something to do with it.

Oh my God, if you were to ever go there and just go to a few of the graveyards around that farm, you would stumble over one little, tiny gravestone after another after another. I mean, infant mortality rates were through the roof. And it was actually bad luck to name your baby before it reached one year old. And Bathsheba Sherman was by some, I guess, accused of practicing witchcraft. She was apparently a very beautiful woman and the other women in town were threatened by her. It was back in the time when folklore and old wives tales and the accusation of being a witch could get you killed up in San Luis, which was just like an hour north of where we were living. And had it been a little bit different time, she could have paid with her life for being accused of that. But instead, it was just a vicious rumor that circulated that she had killed the baby for making a deal with the devil for eternal youth and beauty. We listen to all of that now and say, “Well, that’s just stupid. You know, that’s just superstitious nonsense. The woman would not be buried in the middle of hallowed ground in the Riverside Cemetery in Harrisville next to her husband and all of her children had there been any proof that she was a practicing witch.” I will spend the rest of my life defending her because even though I don’t know for certain if she had anything to do with the death of that child, I don’t think it’s fair to accuse someone of murder unless you have some evidence as proof. And there was no evidence back then. There was no DNA. There was nothing. And so, I just don’t think that she had anything to do with that.

I think that it was a very unfair condemnation of her. But unfortunately, the Warrens were asking my mother to be able to do an investigation of the house. My mother told her what she knew about the history of the house. After Lorraine came up with that name, my mother said, “Well, I’ve been doing some historical research on this property and some surrounding properties in the area.” And she showed Lorraine her notebook that was filled with stories and birth certificates and death certificates. On her second or third visit, Mrs. Warren asked for the notebook, and it was filled with descriptions of the spirits in the house. It was filled with drawings of the spirits that my mother had seen. And Mrs. Warren asked if she could borrow that thick notebook of absolutely invaluable information. And she wanted to make Xerox copies of it, so it tells you what time in history that was. My mother begrudgingly handed it over to her with the promise that she would get it back. But she never did return it. Mrs. Warren kept it. It was our understanding that when the movie The Conjuring was made that that notebook was sold as part of her case files. And it’s gone. We never ever saw it again. My mother asked for it back.

My mother felt that it was part of her legacy to her children. Mrs. Warren perceived it to be a haunted item and didn’t think that it belonged in the house. So, she told my mother she would return it, but then she never did and like 15 years later, she sold it. A number of things that we had found on the property went missing when they came one night with their team. It was the night of the séance that they foisted upon my mother, insisting that she was being oppressed and that she was right on the verge of possession and if they didn’t intervene on her behalf at that point that she would be lost. That was the most horrible night of my life. I was 15 when that happened. And I remember it like it just happened. It was absolutely traumatizing. I suffer PTSD from it. I swear to you I do. It was just a few minutes, but in those few minutes, I saw the dark side of existence and that is why I choose deliberately to live in the light. I will never let anything that evil touch me. I never will.

The Warrens only came maybe five times over the course of about a year and a half. And the last time that they came was after the séance. And when my father threw them out of the house that night along with their entourage, they left that house with my mother unconscious on the parlor floor. They came back to see if she had survived that night because when they left that house, they didn’t know if she was dead or alive. It was horrible. I don’t want to disparage them. They can’t defend themselves. Mrs. Warren, I think her heart was in the right place. I mean, she was a collector of objects. Their paranormal museum didn’t make itself. Every investigation she ever did, she had something from that investigation that went into their paranormal museum. And I know people personally who’ve been through it and have seen items that disappeared from our house the night of the séance that are under glass in that museum now.

BD: Do you know if that notebook was in their paranormal museum?

AP: No, it never was. Not that I know of. No, that was kept separately.

BD: What were your interactions with the Warrens like during the times that they were doing their investigation?

AP: Mrs. Warren didn’t really have anything much to do with us, with the children. She kind of turned us over to Ed, and he’s the one that interviewed us individually. My little sister, April, had a friend, a spirit friend, up in the chimney closet between the first and second bedroom. And she wouldn’t tell them about him. And he had identified himself to her as Oliver Richardson. But she wouldn’t tell Ed about him because she was afraid that the Warrens would make him go away and she loved him. And she felt very protective of him. And he was basically the same age as she was in life when he died. So, they had a very strong connection that she was not willing to jeopardize by telling them anything about him. But the rest of us just spilled our guts. It was kind of cathartic. It was a relief to be able to talk about the activity in that house with someone who believed us.

The night that Mrs. Warren originally came to the house, Mrs. Warren told my mother that I was in the room. I was a witness to this conversation. And she told my mother that the reason, even though she had known about our predicament for a number of weeks, she decided that she and her husband would not come out to the house until Halloween was because she said that’s when the veil has thinned. And I remember my mother looking at her and then kind of not laughing because it was certainly not a laughing matter, but kind of this incredulous grunt came out of her like, well, and then she just looked at her and she said, “Well then, I guess every day is Halloween at this house and there is no veil. I don’t know what you’re talking about, this veil. There’s no veil here. We share this with a lot of spirits.” One of the things that my mother resented about the film The Conjuring—I understand why they did what they did. I get it. But what they tried to do is juxtapose the devout Roman Catholic paranormal investigators, Ed and Lorraine Warren, against the godless heathen parent family. You know, like we were, I won’t say pagan because pagan is a religion also, but that we didn’t have any connection to the church. And my mother took great exception to that. She didn’t even watch the film until it had been out on DVD for more than a year.

I thought that she would be very upset about the way she was represented in the film. Some of it she thought was just so ridiculous that it was not anything that she would bother to take exception to. But the one thing that she was really offended by was that our portrayal was that of a family that had no faith. And nothing could have been further from the truth. My father was born and raised in a staunch Catholic tradition as the eldest of six boys. Church was an integral part of his childhood and his family’s life. He went to parochial school, and he served as an altar boy for years of his youth. And when he graduated from high school, he went into the Navy with the intention of serving the country and then going immediately into seminary to become a priest. That’s what my father’s life plan was. And in the interim, he met my mother and fell in love. And so, the priesthood thing was out the window. But my mother, who he met in Georgia, was a Southern Baptist. And she had to convert to Catholicism in order to marry him. All of us were baptized and all of us made our first communion and all of us were raised in the Roman Catholic Church.

It was the second year, the second Easter that we were at the farm. April was seven years old, and we went to Easter Mass, and we filled our own pew. There were so many of us. And at the very end of Mass, the priest said, “and the father and the son and the Holy Ghost.” And April turned and just with her big blue eyes just looked up at my mother and she said in her big girl, outdoor voice, “See, Mom, God has ghosts just like we do.” And every single head in that church turned and looked at our family. And as we got up to leave, the priest followed us out and he came up to my father and he said, “Mr. Perron, I would appreciate it if you would take your family and worship elsewhere.” My father was so angry and so hurt that he felt abandoned by the religion that he had invested himself into his whole life. I have rarely seen my father cry and he cried on the way home that day. As we were all getting out of our big Pontiac Bonneville car, which we called the Catholic Mobile because it had room for seven plus luggage and the family dog, my mother said, “Girls, if you want to know God, go to the woods. Go to the woods.” We never ever went back to church again. Ever. Our family has never been together in a church ever since then.

BD: That’s awful for a priest to react that way to a child.

AP: The priest was afraid. He was afraid that he had that weird family from the old, haunted house up on Round Top Road in St. Patrick’s Parish. And that others might not come back to the parish if we were there. I was already in catechism classes to make my confirmation and, you know, all my friends were Catholics. Everybody went to St. Patrick’s. I would just go and kind of sit in the back of the class and all my peers were there who were getting ready to make their final confirmation into the church. It was the nuns who were teaching us. But one night, the priest was there, and he recognized me. And sure as hell, not a week later, my parents received a letter from the Bishop, who was the head of the diocese of Providence, informing my parents that I was not welcome in confirmation classes because I asked too many questions. That was it. There was something about living in that house that made you more faithful. And I found out very early on that when all hell was breaking loose in that house and there was a lot of negative energy swirling in the house, or I felt threatened or any of my sisters felt threatened, all you ever had to do was say, “Oh God, help me. “And it stopped instantly. Good conquers evil and love conquers fear. And hatred is not the opposite of love. Fear is the opposite of love and hatred is born of fear.

I believe in my heart that the Warrens had the best of intentions. 40 years later, when I saw Mrs. Warren again out in California when she and I had been invited to preview The Conjuring before it was released, she recognized me immediately and came and wrapped her arms around me. During those three days that we spent in California together, she told me that she and Ed were in over their heads the moment they crossed the threshold of that house. They just didn’t know it. She admitted terrible mistakes were made. They didn’t mean to stir up activity, but she was a bona fide clairvoyant. She had great abilities, and she didn’t always use them to their greatest good. And I think that that was because of her fascination but also her reverence and respect for spirits. She knew that spirits were real, but unfortunately, because of her sensing Bathsheba in the house, who was really only a neighbor—Her sense of that spirit’s presence is what changed everything. Because not only did she have a sense of her presence and we didn’t find out until five decades later that her husband, Judson Sherman, died on that property. We still don’t know how he died. One of my historian friends dug up that he died at the Arnold state. We don’t know how, but that would explain why her presence would be there. You know, spirits are free to come and go as they please.

They’re not locked into an earthbound, specific location. There are differences of opinion even within our own family about how free the spirits are. My sister Cindy will still argue with me about it. She believes that they’re attached to the farm because she said that when we moved, they loved us so much that if they could have come with us, they would have. My response to her is that the spirit that was standing behind Nancy on the front porch of that house the day the whole rest of the family left for Georgia was the spirit that was standing behind my sister Cindy when we arrived at the new house in Georgia. Same exact woman; same entity standing right behind her. And Cindy’s like, “No, no, it must have been somebody else. It must have been one of my guides because the spirits are stuck there. They’re trapped there. And I’m like, “No, they’re not, babe.”

‘The Conjuring’ Movie House – Photo Credit: J. Patrick Swope

BD: How much of what we see in The Conjuring really happened?

AP: There are so many discrepancies between The Conjuring and the real story that is documented in House of Darkness House of Light, the trilogy of books that I wrote that they are unrecognizable except for the names. Everybody that was associated with the film read my books, including the actors, except for maybe the youngest children couldn’t read them. But everybody, all the adults for sure, read the books and said, “Oh, hell no, we can’t tell this story,” because they were about to invest somewhere between $25 and $30 million into making this film. And it was based predominantly on the case files of Ed and Lorraine Warren. It says right on the movie trailer, case files of Ed and Lorraine. But I gave them permission to use anything that was in my books that was the actual story, the authentic telling of our family memoir. And they wouldn’t. The screenwriters, Chad and Carey Hayes, twin brothers, lovely men, wanted desperately to include elements of the true story and they wrote some of the stories into the screenplay. And every single time the suits at New Line Cinema and Warner Brothers sent the script back and said, “Take that out, redact it. We’re not going to run people out of the theater. We’re not going to make a movie that nobody will stay to watch to the end because they are terrified.” So, The Conjuring is a very toned-down version of events.

BD: Why didn’t they want to use it?

AP: They thought it was too scary; it was too real; it was too raw. It was, I mean, people who read my trilogy of books are changed. They are never the same again. When they come up for air after that deep dive, they think about everything differently. Nothing is ever the same. A lot of my readers over the years have deemed it interactive literature. They feel like by the time they’re done reading volume three, that they lived there with us, that they grew up with us, that they know every member of my family intimately well, and that they had the same experiences that we did. There’s something about this story that unlocks a person’s third eye and opens them to the netherworld in a way that nothing else ever has or ever could. Actually, the ability to expand human consciousness is not the most important part of the trilogy. House of Darkness House of Light got its title from my mother when I was about 300 pages into the first book. And she asked me what I was going to title the trilogy, and I told her I didn’t know. And she stood next to me at her old cherry desk right here in the room in which I’m sitting speaking with you right now. I wrote those books in this house. And she just looked at me and she said, “House of Darkness House of Light,” it was both. No comma, it was both. And so, there is no comma. It’s House of Darkness House of Light as one thing because my mother believes the same way that I do; that everything is energy, and everything is consciousness, and everything is one thing.

There is no delineation between natural and supernatural, between normal and paranormal. At least there isn’t for us. This is just how our lives are now. That you cannot experience what we did immersed in that environment for a decade and be unchanged by it. And I think the greatest value in me finding the courage to finally tell our story more than, I didn’t even start writing it until more than three decades after we had left. But I finally got to an age and a place in my own mind where I didn’t care how people were going to react to it anymore. I knew that we would be scrutinized. I knew that we would be belittled. I knew that there would be mean-spirited people out there that would attack our family. And instead, we were embraced by the paranormal community worldwide.

I would not be one of the very best-selling authors in this genre worldwide had it not been for The Conjuring. So, I don’t hold any grudges. The power of a well-made feature film and the images that are placed in people’s minds is what causes them to dig deeper. And based on a true story, well where’s the true story? Who wrote the true story? All they have to do is Google the name Perron and up come the books. They’ve been read all over the world. Hundreds of thousands of copies have been sold. And they’re selling better now than they did after the film came out. So, the story is getting around. And I think that the great value of the story is not the expansion of human consciousness. It is liberating people to tell their own story. Because so many people have been touched by spirits and they’re afraid to share it. They’re afraid to speak out. They’re afraid to be criticized and to be treated as somehow less than. Or I’ve often been asked, “Was there ever a time that you questioned your own sanity?” Oh, hell yes. And that is true of every member of my family. We saw things in that house that there’s no plausible explanation other than spirits are real.

We’re still learning things about that house and about the spirits who quote unquote live there, who dwell there. And I love them. I even love the cranky ones. I do because to me it doesn’t even matter who they were, that they still are is a freaking miracle. That is magical. That is cosmic forces beyond our comprehension. One of my famous quotations is very simple, but it’s very true—To be touched by a spirit is not a curse, but a blessing. It is that rare glimpse into the realm from which we come and will all inevitably return. And I end it with, be not afraid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.