Editorials

‘Phantasmagoria,’ PC’s Best and Most Dated Horror Game, Turns 21

On the anniversary of Roberta Williams’ groundbreaking, under known PC horror game, we look at what makes ‘Phantasmagoria’ so special

“Pray it’s only a nightmare.”

When the survival horror genre of video games comes to mind, the usual suspects that see discussion are titles like Resident Evil, Silent Hill, Dead Space, or even something like the Clock Tower series. One game that stays out of the spotlight, even though it was a formative title for video games and one that sold just as well as any of the aforementioned franchises, is Phantasmagoria from Sierra On-Line. In the days of the ’90s, point-and-click adventure games reigned supreme, with LucasArts and Sierra being the “Nintendo and Sega” of the area and leading the pack for PC gaming. Roberta Williams was Sierra’s wunderkind and the designer responsible for a number of hit franchises like King’s Quest, Mystery House, and The Colonel’s Bequest. She’s also the person largely responsible for adding a graphical interface to adventure games in the first place. But in spite of the many titles that Williams worked on, she’s said that her sole entry in the horror genre, Phantasmagoria, is her favorite.

Phantasmagoria is no doubt one of the biggest spectacles of gaming—something that was especially true in 1995. No expense was sparred here and the game sprawled across 7 CD-ROMs (8 on the Sega Saturn port) due to the heavy amount of FMV (Full Motion Video). Even the game’s description on the back of the box is also more cerebral and mood-setting horror than something that actually tells you what the game is about. More unconventional elements like this were great for setting the tone of this horror experience. Williams had been wanting to do a horror game for a while now (her desire in the matter was probably made increasingly urgent due to the fact that her previous game was Mixed-Up Mother Goose Deluxe, which, by the way, is pretty awesome as far as Mother Goose games go, FYI…), but in a very James Cameron sort of way had been waiting eight years until technology was at a point where she thought she could do properly do the genre justice. Williams wrote a 550-page script for Phantasmagoria, (a typical movie screenplay is around 120 pages, as a point of reference), which required a cast of 25 actors, a production team of over 200 people, took two years to fully develop and four months to film. Phantasmagoria’s initial budget was $800,000, but by the end of production costs had hit a staggering total of $4.5 million (with the game also being filmed in a $1.5 million studio that Sierra built specifically for it). Other luxuries were also brought in like a professional special effects team to handle that area of the game and a choir of over 100 people being assembled to achieve the game’s opening theme.

In spite of these many gambles Phantasmagoria was a huge success, bringing in over $12 million in its opening weekend alone and being one of the best selling games of 1995. To take this one step farther, Sierra’s stock rose from $3.875 in June of that year and was up at $43.25 by September, primarily due to the anticipation and impact of Phantasmagoria, which is just insane. This game is a perfectly fitting example of when some new sort of technology comes out and absolutely everyone has to experience it, not to mention that the advent of FMV technology would also leave a considerable impact on the gaming landscape, too. Sierra would continue to use this technology on The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery, while some game developers from other studios even began to worry that these ultra-productions of games that spanned many CDs would become to be the expected norm, with them fearing the danger of game’s losing core fundamentals in favor of showmanship.

Phantasmagoria was not the first title to use FMV technology, but they featured a mix of both real actors in the cutscenes as well as real actors in 3D rendered environments leading to a curious product. Most video games of the time would feature somewhere between 80 to 100 backgrounds, but Phantasmagoria had more than 1000. The game’s graphic violence and content also led to some controversy where the title was attacked by a number of people, refused to be carried by some retailers, and was outright banned altogether in Australia due to their censorship laws. There was a password-operated censorship system in the game to tone down the violence, but that didn’t seem to placate anyone. Unsurprisingly, all of this red tape around the game just made horror fans crave it even more. It was the perfect marketing tool.

The story in Phantasmagoria is hardly anything revolutionary. Newlyweds, Adrienne and Don, move into a house in Massachusetts that was once owned by a practitioner of the dark arts. This evil soul takes hold of Don while Adrienne must survive this nightmare and figure out the mystery behind it all. If Williams didn’t go ahead and cite The Shining as a major influence here, it would still be pretty obvious that the game takes inspiration from the classic film. Don’s possession feels much like Jack Torrance’s and he gradually becomes more unhinged as this house and the spirit inside it take stronger hold over him.

In terms of gameplay, Phantasmagoria is no different than the majority of point-and-click adventure games of the time, with familiar trial and error mechanics stringing everything together in a way that Sierra did like no other. Puzzles take a backseat to the FMV here, resulting in the difficulty being a little disappointing and condescending by King’s Quest standards. Honestly, it’s frustrating how little you’re actually controlling this game, with so much here seeing FMV sequences finishing your sentences with you only having the briefest of interactions along the way. This also inevitably leads into a lot of heavy exposition where video is just telling you backstory rather than you actually playing a game. The assumption present is that all of this is forgivable and fascinating due to the graphical innovations that are present. All of this becomes kind of laughable when you look at the screen within a screen that the FMV plays out of so it can optimize correctly. There’s so much wasted space here that it becomes almost as big a focus as the video itself.

It’s a little insane how much the game banks off of you being wowed by all of this. For example, one sequence sees Adrienne rooting around with a letter opener for literally three minutes, only for nothing at all to be achieved. Sequences like this happen simply because the game’s production team believes that literally anything shown through FMV is fascinating and groundbreaking. There’s an exceptionally long sequence of Adrienne tearing down a wall to get through where it really shows all the boards getting broken to great detail, pulling off the most comprehensive “wall tearing” animation to date. Much of this attitude fuels the game where weird amounts of focus are placed on random animations or elements that ultimately aren’t important. It’s a good barometer for where FMV games were at during this time, gamers’ brief obsession with them, and why they were quickly abandoned accordingly.

Characters are always a crucial part of a horror game (or film) and as mentioned before, Williams’ title assembles a roster of 25 weirdos to bring this story to life. It’s a little comforting to see Williams leaning into stereotypes as a means of automatically filling in backstory. It’s not the most progressive things to do, but it’s an approach that works for horror. Especially for a video game made in 1995. Who’s the deepest video game character from that time period that comes to mind? Crash Bandicoot?

Some of the more standout additions to the cast come in the form Cyrus, who could give Of Mice and Men’s Lenny a run for his money (at one point he pulls down a tree to fashion into a bridge, and exclaims, “Of cowse I did! I’m stwong!”), and his mother Harriet, with weirdness constantly emanating off of them. Cyrus nearly mutilates a cat in one scene with all of this shocking content automatically becoming a little hokey due to the FMV filter it’s coming through. Then, the villain during all of this is an evil magician named Zoltan Carnovasch of all things, which seems more like a wizard foe from out of King’s Quest instead. Don’t worry though, if that name seems like a little too much, his magician stage name is Carno, so dealer’s choice here. After a magic trick went wrong, Carno became coma bound before becoming an evil spirit that has a heavy case of revenge on his mind.

Through Williams’ career she began to become known for her unforgiving adventure games where gamers could actually be punished and die on their quests, making saving a necessity and experimenting a tense experience. Phantasmagoria’s environment feels tailor-made for a game that’s focus is horror rather than adventure, and while not quite hitting the same tense heights from other titles from Williams’ oeuvre, watching your character die and fail on their journey does give this game a tremendous amount of charm (especially with the production quality of all of these ridiculous death sequences). The majority of these are saved until the latter moments of the game, but they certainly make an impact.

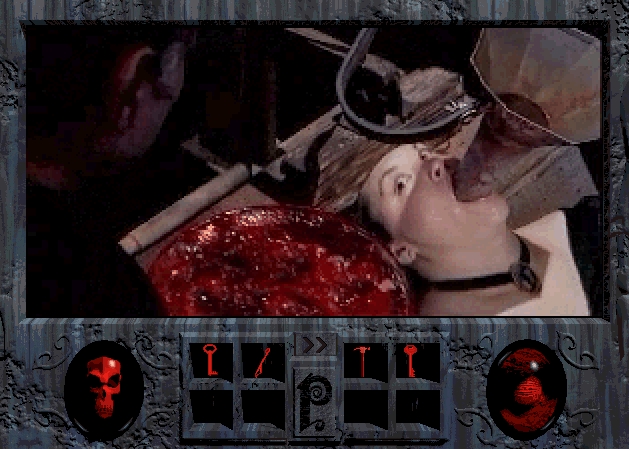

On the topic of these death sequences, it’s worth discussing the many murders from Phantasmagoria to a more thorough degree since they yield such significance. Carno arguably operates with a sort of Freddy Krueger black wit to his murders, which is never a bad thing in my opinion. Each of his executions contain some sort of excuse me? element that you just can’t believe. There’s a murder in the greenhouse, where it looks like a woman is being fed dirt until she dies, and then gets a trowel to the mouth to top it all off. Another seemingly innocent scene between Carno and his wife, where they share fine wine and toast one another leads to a sequence that’s almost too ridiculous to explain. It’s a moment that gives the Joker’s “pencil trick” in The Dark Knight a run for its money and is capped with the perfect line of, “No, here’s to you.” There’s such a sadistic glee in the murders here that it’s hard to not think that Williams is being tongue in cheek on the topic.

One particularly violent ending for Adrienne sees Don putting you in the Throne of Terror, punching you in the face, repeatedly calling you a bitch, and then hit in the face all You’re Next style. This all actually works due to how graphic and aggressive it is. Another prime example is this neck breaking murder which is one of the more disturbing, graphic things you’ll come across in a video game, in spite of how much further the form has come at this point. Using real people and the simple brutality of it all gives all of this material a lot more weight. This might feel like a campy B-horror movie 90% of the time, but it’s scenes like these that briefly make you think that you’ve flipped over to a snuff film. The best death of them all though—and one that I still find difficult to watch—is where Carno kills Regina by putting a funnel in her mouth and jamming food down it into her throat. And by food, I mean things like tripe and “scrambled brains.” If the subject matter doesn’t get you, the sound design on the scene will. More great work here. Finally, it’s kind of ridiculous that the final act of the game sees a huge Xenomorph-esque demon coming to be, but the ways in which he deals with you if you’re not fast enough lead to maybe the best piece of animation in the entire game.

The deaths are clearly a big takeaway from Phantasmagoria and part of what gave it its reputation in the first place, but there’s still plenty of other weirdness in this title. 1995 may be in the infancy of survival horror as a genre but it’s interesting to see which elements from the title actually manage to be scary and which reek of the clunky medium that they’re being presented in. For the most part, Phantasmagoria is not a scary game, and it’s even a little disappointing as a game in general since so little of this 7-disc survival exercise actually sees you doing much. In that sense, rating Phantasmagoria as a horror film instead is an interesting endeavor. I’m actually a little surprised that someone on the Internet hasn’t gone about and attempted to stitch a narrative together with all of the FMV content. I daresay it maybe does work better as a horror film. It’s not a good horror film, but it makes for a great B-horror movie, and I’ll gladly take one of those any day of the week, especially with the acting going on here.

The game kicks off with Adrienne experiencing an absurd nightmare, which is a lot more WTF and confusing than it is frightening. That being said, this intro now does a great job at sending you back to the ’90s and the “weirdness” of the era. Like this really is just a bizarre hodgepodge of computer graphics set to some eerie chanting that hopes for the best. At other times scenarios like a séance take place because why not! “Scary” concepts are continually thrown in, creating a good picture of the cluttered composition of some of ’90s horror. While on the topic of the séance, during it Harriet happens to vomit, with this vomit appearing to be sentient monster vomit that then begins to tell people what to do. The effects and voice work here actually are kind of impressive for the time, as ridiculous as the concept is. It feels very Hellraiser, surprisingly. Another well-done concept sees you constantly looking into mirrors to no avail, only for the game to finally surprise you and make use of the moment. It’s these instances of toying with your expectations where Phantasmagoria shines.

The game also explores Don ‘s possession in some interesting ways with the whole thing being such an unbelievably over the top performance. At one point he’s literally Pagliacci-ing himself up as a ridiculous culmination of all of this. It’s all just being weird and “creepy” for no reason. There is a scene towards the end of the game where you stumble upon Don’s collection of cut up photos of Adrienne which does tap into a genuinely uncomfortable place, but ultimately falls short. Possessed Don also ends up leading to a rape scene with Adrienne, which was the main factor in the game’s banning. Again, this kind of feels like Williams is going for broke and rebelling from her Mother Goose ways. There is a moment in Phantasmagoria though where you’re told to “Find the dragon…” that almost feels like Williams forgot for a minute that she’s in a horror game and not the land of Daventry.

Perhaps the most bizarre thing here is that after you escape from this huge demon and leave this cursed house, the game’s ending is simply Adrienne walking away in a dazed stupor. Cut to credits. It’s such a weird, abrupt conclusion for a game that tends to make a meal (more scrambled brains, please) out of everything. A sequel to Phantasmagoria was unsurprisingly made, but not with Williams’ involvement due to her being too busy working on King’s Quest VII at the time. Notably though, Williams did express interest in returning for a third title in the series, but obviously that ship eventually sailed. Phantasmagoria 2: A Puzzle of Flesh’s (somehow this has never been used as a Hellraiser subtitle) story is unrelated to the first title and it doesn’t seem to have much of the same charm as the original. The same FMV style is present, but it results in a much clunkier game with deaths that hardly hold a candle to the original.

Phantasmagoria is an odd piece of horror history that deserves your attention if you get the opportunity. Honestly this is the sort of game that’s perfect to have a few friends over where you just mock and laugh at it through the night. It has endless personality, a style that warms your nostalgia glands, and some of the grisliest murders in video gaming.

Plus, it also has the biggest fixation on drain cleaner that I’ve ever seen in a video game.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.