Editorials

‘Puppet Master 4’ at 30: The Horror Tokusatsu Sequel You Never Knew You Needed

One wouldn’t think that a schlocky slasher series about killer puppets would produce more than a dozen films across three decades, let alone sequels that are still being discussed today, yet here we are getting deep in the weeds over the straight-to-video sequel bliss that is Puppet Master 4. Puppet Master is easily the most successful property to come out of Charles Band’s Full Moon Features, best known for movies like Castle Freak and Subspecies, as well as more low-hanging fruit like The Gingerdead Man and The Evil Bong series. Puppet Master falls comfortably between these two extremes. After a satisfying initial trilogy that chronicles the grandiose revenge scheme of a persecuted toymaker, Puppet Master–like many long-running horror series–is forced to ask, “What’s next?”

In Puppet Master’s case, the franchise strangely pivots towards the rehabilitation of Blade, Leech Woman, Six-Shooter, and the rest of these tiny terrors as they’re rebranded as antiheroes who help in the good fight against malevolent stop-motion demons. While an odd choice, it’s not one that’s unprecedented, such as in movies like Critters or The Terminator. More importantly, this decision actually speaks towards the horror sequel’s compulsion to draw greater inspiration from Japanese tokusatsu productions than the slasher genre. All of this makes Puppet Master 4 a surprisingly interesting genre relic, especially on its 30th anniversary with three decades of horror hindsight.

The first three Puppet Master movies, while comparable in tone and execution, each have different directors between David Schmoeller, Dave Allen, and David DeCoteau. A new name is once again chosen for Puppet Master 4, Jeff Burr, who was regarded as a bit of a sequel savant between his previous work on Stepfather II, Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III, and Pumpkinhead II: Blood Wings. Burr doesn’t just become the first director to helm two Puppet Master movies, but the director shoots the fourth and fifth installments back-to-back to create great consistency between the two projects. Burr is really the perfect choice for Puppet Master considering his extensive genre experience, as well as his preexisting history with prosthetics and practical effects.

The previous Puppet Master films were flawed fun, but the smartest decision that Burr makes with this sequel is to turn it into Full Moon’s tribute to the horror tokusatsu genre. It’s important to first understand that “tokusatsu” is a Japanese term for live-action film and television that’s dominated by practical special effects. Tokusatsu started to find mainstream success during the 1960s and it covers a wide range of content, typically sci-fi, fantasy, and war, but there’s also a healthy emphasis on horror. Over time, the tokusatsu genre has been further fragmented into kaiju, superhero, and mecha content, with Puppet Master 4 comfortably fitting into the parameters of the kaiju and superhero tokusatsu sub-genres.

It’s easy to conflate all sentai tokusatsu stories with Super Sentai or Kamen Rider, but Japan has a rich history with frightening horror tokusatsu that are designed to inspire fear over excitement. There are explicit horror tokusatsu series like The Guyver and Tokyo Gore Police, while other established brands dip their toe into this darker degree of content. Ultra Q is an Ultraman horror anthology series that’s akin to The Twilight Zone, while Kamen Rider Kiva explicitly references classic Universal Monsters through its villains. Noboru Sugimura, the writer of Kakuranger (which is what season three of Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers is based on) was even hired to write Resident Evil 2–which is often considered to be the crown jewel of the survival horror gaming genre–because of his work on the tokusatsu series.

With this horror tokusatsu precedent established, Puppet Master 4 ambitiously transforms Full Moon’s Puppet Master from a killer doll franchise into a horror tokusatsu film akin to Power Rangers or Ultraman. Puppet Master 4’s reliance on these tropes is why the film still resonates three decades later and is a turning point for the franchise when many new, younger fans jumped on board and the franchise started to redefine itself through its sequels. Burr even uses this experience and goes on to direct Beetleborgs, an American sentai tokusatsu production.

On this level, Puppet Master 4 is really a fascinating relic and the perfect time capsule for 1993 when this style of tokusatsu action series were at a mainstream high in America. The film even starts with an introduction where a man-in-suit monster commands his demonic minions while they stare into a prophetic cauldron as they plan to invade the real world from their dark realm. It’s no different from a Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers episode that kicks off with Rita Repulsa setting the stage for the Rangers’ latest villain. It’s no coincidence that Puppet Master 4 begins with these new tokusatsu characters rather than the classic Puppet Master figures or Andre Toulon.

Puppet Master 4 is also ripe with other tokusatsu staples here like all of the “Capital S Science” activities that go down in the vague BioTech Industries. Sutekh’s evil totems even look like the toys that Rita Repulsa transforms into her giant tokusatsu monsters. Additionally, Sutekh totems steal souls like they’re Doctor Sleep’s True Knot sapping steam from scared kids. Even the film’s young protagonist, Rick Myers (Gordon Currie), who teams up with Toulon’s puppets, is very much in the mold of a Power Rangers lead, like Billy. His group of friends also feel very much like a group of Rangers, too. One of Puppet Master 4 ‘s livelier scenes involves a Battlebot laser tag training exercise that feels like some Zordon training exercise. On that note, Puppet Master 4 practically presents Toulon as a Zordon-esque figure with an ancient rivalry against Sutekh, like any tokusatsu feud. The movie’s big electricity explosion ending also has a lot more in common with a standard Power Rangers episode than any other Puppet Master movie or Full Moon Features film.

There’s still violence and death in Puppet Master 4, like its predecessors, but it does feel like a softer reboot that’s specifically meant to appeal to younger audiences with anti-heroes who they can root for rather than the lurid slash-fest that are the first three movies. The franchise’s signature Nazi iconography is almost entirely absent in this picture with an emphasis on demons over fascists. Puppet Master 4 even ends with Toulon’s puppets saluting their new, younger puppet master who’s clearly positioned to be the franchise’s new protagonist and de facto Toulon replacement moving forward. None of the Puppet Master movies are particularly long, but at only 79 minutes (75 without credits), Puppet Master 4 isn’t even as long as Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers’ two theatrical efforts. While on the subject, Maligore and Elgar from Turbo: A Power Rangers Movie are also more intimidating and frightening than Puppet Master 4’s Sutekh.

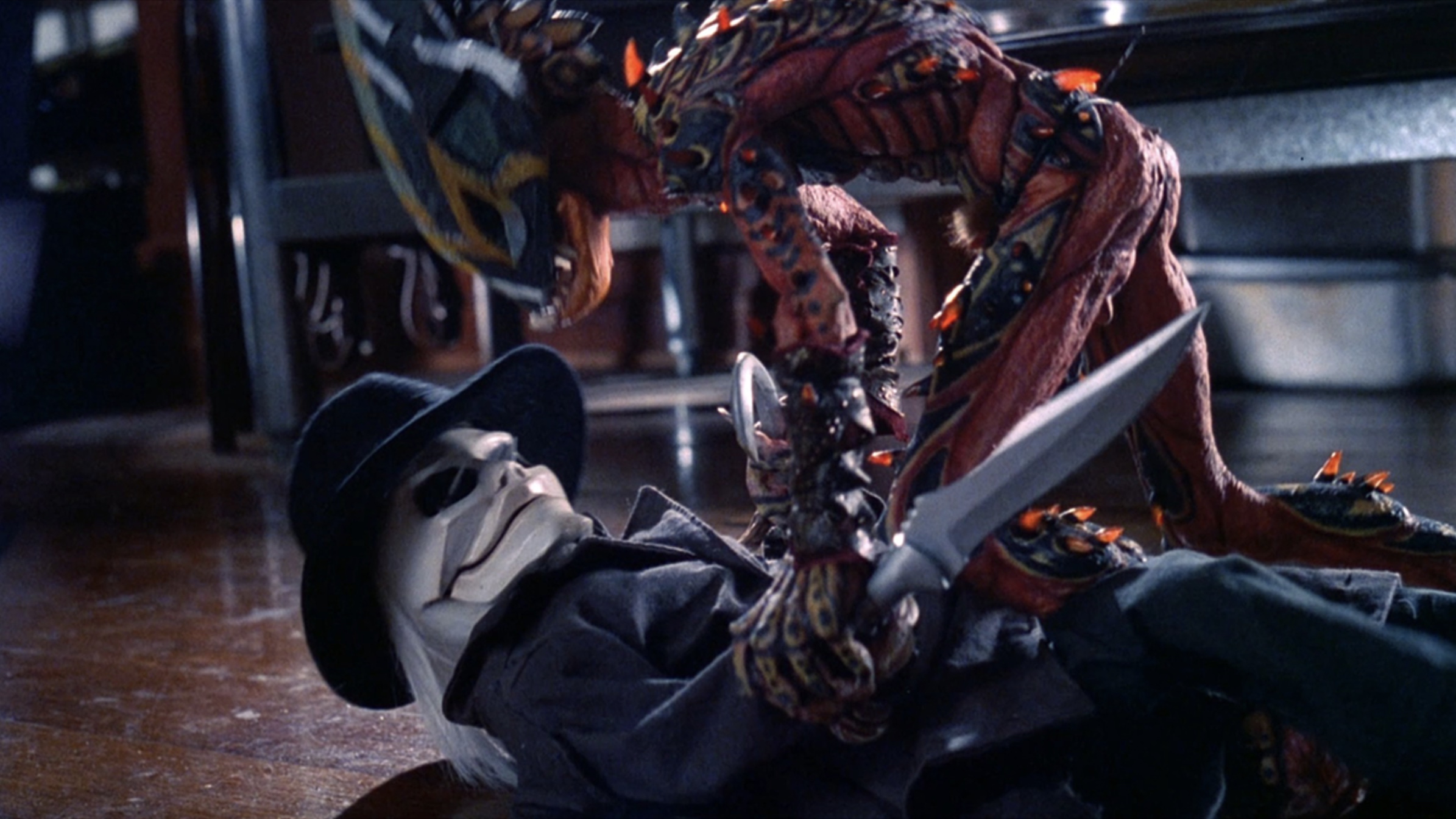

What does feel representative of past Puppet Master films is the entertaining stop-motion battle sequences between the puppets and demon totems. It’s also particularly satisfying to see these puppets work together as a team and deliver killer cooperation as opposed to the previous movies where they’d usually divide and conquer with each puppet getting their own separate murder set piece. While that has its charm, it’s also quite fulfilling to watch the puppets pool together their unique abilities while they eviscerate demons. Their teamwork also results in some oddly comical gags, like Pinhead concernedly wiping demon blood off of Tunneler’s drill after a massacre. This added humor and levity feels like another attempt to appeal to the younger crowd even though the previous Puppet Master movies weren’t bereft of black comedy. This also feeds into what’s arguably the best sequence in the movie, where all of the puppets work together to pull off a Frankenstein’s Monster-like resurrection for Toulon’s prized game-changing puppet, Decapitron. It’s a stop-motion marvel that’s reminiscent of what Phil Tippett does decades later in Mad God.

Alternatively, Toulon’s head being superimposed on Decapitron to impart wisdom during the film’s conclusion is such a ludicrous fever dream of a visual that’s pure Full Moon camp. One has to respect Puppet Master 4 for attempting such a sequence. On the topic of Decapitron (who was actually designed for another movie before being co-opted into Puppet Master), a puppet with many change-able heads that have different functions is a novel idea. It’s reminiscent of Mike Mignola’s The Amazing Screw-On Head and actually a great direction to take the series, which makes it a shame that this compelling concept doesn’t really receive further development.

There’s tremendous value in a horror tokusatsu project, as wild as that sounds. However, it’s understandable why Puppet Master 4 didn’t kickstart this trend, but it’s easier to picture it succeeding three decades later if the right, passionate genre filmmakers were involved. Jordan Peele, Guillermo del Toro, or even Robert Rodriguez would excel in this territory and absolutely nail the assignment. Puppet Master 4 doesn’t rejuvenate the bloody B-horror slasher series in the way that it hoped to, but three decades later it’s still built a legacy and stands out as a cult classic, albeit for different forward-thinking genre reasons.

Editorials

‘Devil’s Due’ – Revisiting the ‘Abigail’ Directors’ Found Footage Movie

Expectations can run high whenever a buzzworthy filmmaker makes the leap from indie to mainstream. And Radio Silence — Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, Tyler Gillett, Chad Villella and former member Justin Martinez — certainly had a lot to live up to after V/H/S. This production collective’s rousing contribution to the 2012 anthology film not only impressed audiences and critics, the same segment also caught the attention of 20th Century. This led to the studio recruiting the rising talent for a hush-hush found-footage project later titled Devil’s Due.

However, as soon as Radio Silence’s anticipated first film was released into the wild, the reactions were mostly negative. Devil’s Due was dismissed as a Rosemary’s Baby rehash but dressed in different clothes; almost all initial reviews were sure to make — as well as dwell on — that comparison. Of course, significant changes were made to Lindsay Devlin’s pre-existing script; directors Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett offered up more energy and action than what was originally found in the source material, which they called a “creepy mood piece.” Nevertheless, too many folks focused on the surface similarities to the 1968 pregnancy-horror classic and ignored much of everything else.

Almost exactly two years before Devil’s Due hit theaters in January of 2014, The Devil Inside came out. The divisive POV technique was already in the early stages of disappearing from the big screen and William Brent Bell’s film essentially sped up the process. And although The Devil Inside was a massive hit at the box office, it ended up doing more harm than good for the entire found-footage genre. Perhaps worse for Radio Silence’s debut was the strange timing of Devil’s Due; the better-received Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones was released earlier that same month. Despite only a superficial resemblance, the newer film might have come across as redundant and negligible to wary audiences.

Image: Allison Miller in Devil’s Due.

The trailers for Devil’s Due spelled everything out quite clearly: a couple unknowingly conceives a diabolical child, and before that momentous birth, the mother experiences horrifying symptoms. There is an unshakable sense of been-there-done-that to the film’s basic pitch, however, Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett knew that from the beginning. To compensate for the lack of novelty, they focused on the execution. There was no point in hiding the obvious — in the original script, the revelation of a demonic pregnancy was delayed — and the film instead gives the game away early on. This proved to be a benefit, seeing as the directors could now play around with the characters’ unholy situation sooner and without being tied down by the act of surprise.

At the time, it made sense for Radio Silence’s first long feature to be shot in the same style that got them noticed in the first place, even if this kind of story does not require it. Still and all, the first-person slant makes Devil’s Due stand out. The urgency and terror of these expectant parents’ ordeal is more considerable now with a dose of verisimilitude in the presentation. The faux realism makes the wilder events of the film — namely those times the evil fetus fears its vessel is in danger — more effective as well. Obviously the set-pieces, such as Samantha pulling a Carrie White on three unlucky teens, are the work of movie magic, but these scenes hit harder after watching tedious but convincing stretches of ordinariness. Radio Silence found a solid balance between the normal and abnormal.

Another facet overlooked upon the film’s initial release was its performances. Booking legitimate actors is not always an option for found-footage auteurs, yet Devil’s Due was a big-studio production with resources. Putting trained actors in the roles of Samantha and Zach McCall, respectively Allison Miller and Zach Gilford, was desirable when needing the audience to care about these first-time parents. The leads managed to make their cursory characters both likable and vulnerable. Miller was particularly able to tap into Samantha’s distress and make it feel real, regardless of the supernatural origin. And with Gilford’s character stuck behind the camera for most of the time, the film often relied on Miller to deliver the story’s emotional element.

Image: Allison Miller in Devil’s Due.

Back then, Radio Silence went from making viral web clips to a full-length theatrical feature in a relatively short amount of time. The outcome very much reflected that tricky transition. Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett indeed knew how to create these attention-grabbing scenes — mainly using practical effects — but they were still learning their way around a continuous narrative. The technical limitations of found footage hindered the story from time to time, such as this routine need to keep the camera on the main characters (or see things from their perspective) as opposed to cutting away to a subplot. There is also no explanation of who exactly compiled all this random footage into a film. Then again, that is an example of how the filmmakers strove for entertainment as opposed to maintaining every tradition of found footage. In the end, the directors drew from a place of comfort and familiarity as they, more or less, used 10/31/98 as the blueprint for Devil’s Due’s chaotic conclusion. That is not to say the film’s ending does not supply a satisfying jolt or two, but surely there were hopes for something different and atypical.

Like other big film studios at that time, 20th Century wanted a piece of the found-footage pie. What distinguished their endeavor from those of their peers, though, was the surprising hiring of Radio Silence. Needless to say, the gamble did not totally pay off, yet putting the right guys in charge was a bold decision. Radio Silence’s wings were not completely clipped here, and in spite of how things turned out, there are flashes of creativity in Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett’s unconventional approach to such a conventional concept.

Radio Silence has since bounced back after a shaky start; they participated in another anthology, Southbound, before making another go at commercial horror. The second time, as everyone knows, was far more fruitful. In hindsight, Devil’s Due is regarded as a hiccup in this collective’s body of work, and it is usually brought up to help emphasize their newfound success. Even so, this early film of theirs is not all bad or deserving of its unmentionable status. With some distance between then and now, plus a forgiving attitude, Devil’s Due can be seen as a fun, if not flawed first exposure to the abilities of Radio Silence. And, hopefully, somewhere down the line they can revisit the found-footage format.

Image: Allison Miller and Zach Gilford in Devil’s Due.

You must be logged in to post a comment.