Editorials

9 Horror Franchises That Should Be Turned into TV Shows

The film and television industry loves dipping back into previous intellectual properties. And though it’s sometimes depressing, it’s also understandable. If a recognizable name or character has the potential to bring in a larger audience than an original concept, they’re going to try it.

With the explosion of long-form content on TV and streaming outlets, it makes sense that they’d also try to milk those concepts for all they’re worth by turning them into series. It’s not a totally new phenomenon, but the frequency has increased in recent years.

The movies chosen to turn into TV series fall into a few categories: Good or Great (Hannibal, Ash vs. Evil Dead, The Exorcist, Bates Motel, Wolf Creek); Fine (The Dead Zone, From Dusk Till Dawn, Scream); Bad (Damien); Series’ Which Never Had a Chance (Tremors: the Series, Blade: the Series, The Crow: Stairway to Heaven); and Series’ That Are Barely Connected to Their Source Material (Friday the 13th: the Series, Freddy’s Nightmares).

With already announced series’ for The Mist, The Lost Boys, American Gods, and Tremors (again) on their way, perhaps there’s room in the television landscape for a few other horror franchises to become TV’s next big hit. And we’ve got some ideas about that…

Hellraiser

Frankly, I’m surprised this hasn’t happened already. With a deep mythology that runs back centuries, an established presence in the distant future and the 1700s France, and a whole gaggle of visually stunning and disturbing Cenobites just waiting in the wings for their moment to shine, this series has the potential to connect with fans who love the over-the-top weirdness of American Horror Story and the intricate world-building of Game of Thrones. Given that the series has been direct-to-video since the fifth installment, it already feels at home on the small screen.

George A. Romero’s ‘Living Dead’ Series

Though there is an overall sense of zombie fatigue, not to mention the fact that series’ like The Walking Dead and Z Nation have picked clean the bones of what Romero began decades ago, it’s still compelling to consider what kind of intriguing social commentary he could find if given a decent television budget and the hands-off approach of a network like Starz. He could go in a couple of directions, either continuing the anthology-esque nature of the series and having standalone episodes that all take place in the same universe, or he could start to weave together narratives he’s been creating for forty years. Either way, it would be a fitting conclusion to the modern zombie phenomenon to give the man who reinvigorated it the opportunity to finish telling his story.

Saw

Even though another installment of this film is on its way, this is a series that has always begged for the opportunity to stretch its narrative legs. Juggling the personal story of Jigsaw (and his disciples), the people in the traps (and their families or significant others), and the police and FBI, every entry in the series is stuffed with plot machinations. The way the series was produced (with a new film coming out every year at the same time for seven years straight) already operated like a miniature television studio, and the stories would benefit from having a writer’s room to brainstorm all the traps and last-act plot twists.

Resident Evil/Underworld

These wouldn’t be combined into a single show, but they’re grouped here because they have something in common: they would make fun horror-action series’ on Syfy. The network, known primarily for cheesy movies and the occasional brilliant show like Battlestar Galactica and The Expanse, has always gravitated towards action-driven series’ that were out there, but not TOO out there: 12 Monkeys, Dark Matter, Killjoys, Van Helsing. The tone and pacing of movie series’ like Resident Evil and Underworld fit the mold perfectly, with solid genre trappings and just enough silliness and absurdity to appeal to the demographic.

The Purge

No film universe with the expansive and complex background of The Purge should be limited to only taking place for a few hours during one night a year. If the world of The Purge were expanded into a continuing series, the audience would be allowed to see the inner workings of life outside the annual Purge; the political and financial divide, the quiet resentments building up over a year, the psychopaths gleefully counting down the days until the next Purge. And who would know better about whether or not the movies would work in this format than James DeMonaco, the creator of the films, who already considered making it a series. We’re getting a fourth installment of the movie franchise, but there may be a TV show here yet.

The Conjuring

This film series is the most perfectly constructed concept to turn into a TV series: husband and wife supernatural investigators struggle to live a normal, happy life with their family while simultaneously battling demons in the cases they find. It already has the built-in “case of the week” element, and a great gimmick in the “based on a true story” angle. And when the story has the room to breathe that television allows, it will give the creators more time to explore the family dynamic and perhaps start to create a larger mythology for the demon creatures that seem to have targeted Lorraine and Ed. The only downside: television might not be able to afford both Vera Farmiga and Patrick Wilson every week, and I can’t imagine what two other actors they could find that would embody them so wonderfully.

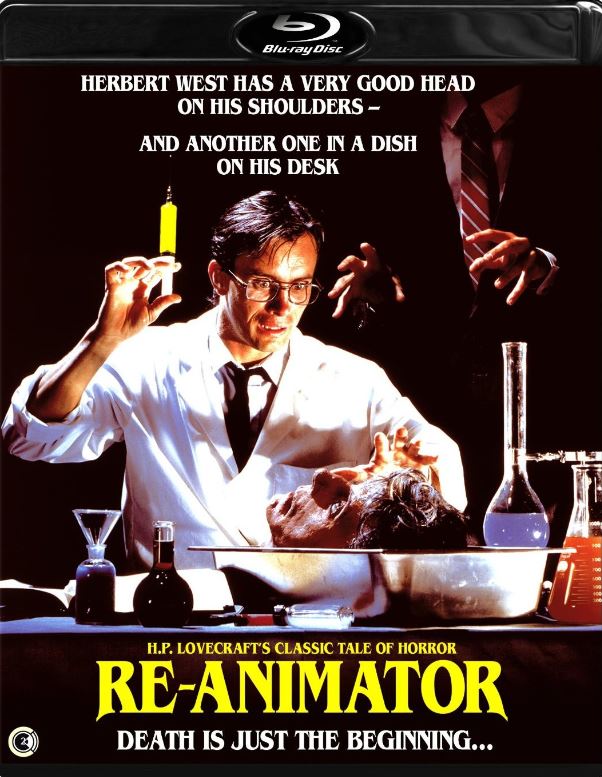

Re-Animator

Making a successful, sustained horror series is hard enough; adding comedy is even more challenging. No one tried it in earnest for a long time, but then Ash vs. Evil Dead came along and shattered all expectations for serialized horror-comedy on television. Now that the way has been paved, it’s time for Herbert West to get his due. The series could either pick up where the films left off, with Herbert West out of prison and experimenting in secret; or it could totally reboot the story. Starz has Ash vs. Evil Dead, IFC has Stan against Evil; Epix, what are you up to?

V/H/S

Many people say that Black Mirror has already taken the mantle of “the modern Twilight Zone.” While that is partly true, one aspect of Black Mirror that is different from The Twilight Zone is its origins: while Black Mirror is brilliant dark satire, it has a specifically British sensibility. The Twilight Zone was as distinctly American as its creator/host Rod Serling, and much of the commentary of the series was filtered through that lens. All three entries of V/H/S touch on uniquely American perspectives in their entries, giving the found footage and anthology subgenres a geographical specificity; getting a weekly half-hour of segments of varying length, style, and plot (but all still in the “captured footage” arena) might lead to another great renaissance in television anthology storytelling.

Which of these would you love to see? And can you think of any others?

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.