Editorials

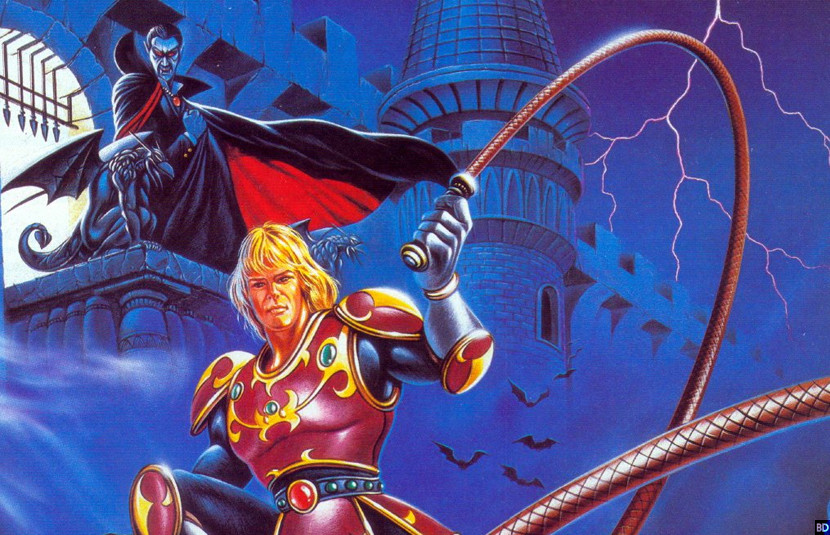

A Horrible Night to Have a Curse: ‘Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest’ Turns 30

It’s been 30 years since Konami first released the sequel to their massive hit game, Castlevania. And yes, Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest wasn’t the follow-up that many fans were hoping for in 1987, and rightfully so. What was a simple yet addictive formula had been tweaked to incorporate elements that bore similarities to another sequel that was totally different to its predecessor: Nintendo’s Zelda II: The Adventure Of Link. It also didn’t help that the game had some significant shortcomings. Serious flaws introduced with the changes ended up frustrating players, leaving them lost or uninterested. However, in spite of this, Simon’s Quest did introduce lay the groundwork for later games in the series.

First, some background: Shortly after the original Castlevania was released on the NES, Konami released Vampire Killer aka Akumajō Dracula for the MSX2 computer in Japan and Europe. The game was essentially an enhanced version of the original game, but was a more open-ended platformer, and required the player to seek out keys in order to progress through the areas. You could also buy items from merchants. Konami took these concepts and used them in Simon’s Quest, which was originally released on the Japanese-only Famicom Disk System or FDS, but eventually made its way to North America in cartridge form.

The story for the game has Simon being afflicted with a cure placed on him by Dracula in the previous game. Simon must now collect Dracula’s body parts that were scattered by his minions after his defeat, resurrect Dracula, and kill him to break the curse. This is where the linear gameplay from the first game is replaced with an open-ended exploration of areas that involve players visiting mansions that hold body parts, which also double as items for the player to use. Along the way, Simon must also purchase items from people in various towns in order to progress. Instead of collecting whip upgrades or subweapons from candles, players must buy them from shopkeepers using hearts that they collect from defeating enemies. Hearts are also used to power some subweapons, so players must “grind” to gain enough hearts from enemies. This grinding aspect of Simon’s Quest, while tedious, is offset by the other introduced RPG element: Leveling. The player will increase in health once they reach the required amount of hearts necessary to gain a level.

Also introduced is a day/night cycle, where after five minutes of game time, the time of day shifts to night (“What a horrible night to have a curse.”) or to daytime (“The morning sun has vanquished the horrible night.”). During the night, enemies are stronger (but drop more hearts), and the townsfolk are nowhere to be seen. Keep in mind that this cycle factors into game’s ending, which depending on how long you take, can result in one of three endings. Given the amount of time players would spend in the game, Konami introduced a save system in the FDS version, and a password feature in the cartridge version.

These concepts – the non-linear gameplay, the experience system, the purchasing of items to progress, the multiple endings, a password/save feature, and even the day/night cycle – were all revisited in subsequent games, and some became staples in the series. However, despite those innovations, Simon’s Quest is still regarded by many as an average game (or worse). Sure, the music is fantastic, and gave fans a series’ mainstay with “Bloody Tears”. But the things that made the original game so much fun, with its punishing difficulty that required players to hone strategy and skill to master, were gone. The danger of death was negated by the fact that you can continue right where you left off if you died. Even then, if you lost all your lives and continued, the punishment was losing your experience points gathered for the next level, and all of your hearts. The game’s bosses are a joke when compared to the previous game’s nightmare fights. Some pose little or no challenge in Simon’s Quest (you can literally walk right past Death and avoid fighting him). Dracula himself is a pushover if you stun-lock him with a certain item.

The biggest flaw, however, was its translation. Konami had done a poor job of localizing the game, resulting in townspeople spouting nonsense that was originally meant to be hints as to what to do (“Get a silk bag from the graveyard duck to live longer.”). Granted, some of the characters in the Japanese version also gave bad advice, but it also easy to determine. Not with the English version. This made the need for a strategy guide a necessity, and unless you subscribed to Nintendo Power, you weren’t going to get one.

So, three decades on, does Simon’s Quest deserve its “black sheep” status in the series? If you look at it from the original NES trilogy? Maybe. The gameplay took a step back, and was overall a more mundane affair compared to Castlevania. For Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse, Konami scrapped the RPG elements, and opted to return to the linear style of gameplay merged with a branching paths concept, and the ability to play as multiple characters. But, the concepts first introduced in Simon’s Quest later showed up in later classic entries like Rondo of Blood, Symphony of the Night and Castlevania 64 (okay, maybe not that one). For that, Simon’s Quest should be seen as “laying the groundwork” for these entries, as well as a curiosity in lieu of outright hatred. It’s not a perfect game, but it still does deserve a playthrough once in a while.

Plus, it did give us this awesome Nintendo Power cover.

This article was originally posted on Plenty Dreadful. Head there for more horror video game goodness!

Editorials

Finding Faith and Violence in ‘The Book of Eli’ 14 Years Later

Having grown up in a religious family, Christian movie night was something that happened a lot more often than I care to admit. However, back when I was a teenager, my parents showed up one night with an unusually cool-looking DVD of a movie that had been recommended to them by a church leader. Curious to see what new kind of evangelical propaganda my parents had rented this time, I proceeded to watch the film with them expecting a heavy-handed snoozefest.

To my surprise, I was a few minutes in when Denzel Washington proceeded to dismember a band of cannibal raiders when I realized that this was in fact a real movie. My mom was horrified by the flick’s extreme violence and dark subject matter, but I instantly became a fan of the Hughes Brothers’ faith-based 2010 thriller, The Book of Eli. And with the film’s atomic apocalypse having apparently taken place in 2024, I think this is the perfect time to dive into why this grim parable might also be entertaining for horror fans.

Originally penned by gaming journalist and The Walking Dead: The Game co-writer Gary Whitta, the spec script for The Book of Eli was already making waves back in 2007 when it appeared on the coveted Blacklist. It wasn’t long before Columbia and Warner Bros. snatched up the rights to the project, hiring From Hell directors Albert and Allen Hughes while also garnering attention from industry heavyweights like Denzel Washington and Gary Oldman.

After a series of revisions by Anthony Peckham meant to make the story more consumer-friendly, the picture was finally released in January of 2010, with the finished film following Denzel as a mysterious wanderer making his way across a post-apocalyptic America while protecting a sacred book. Along the way, he encounters a run-down settlement controlled by Bill Carnegie (Gary Oldman), a man desperate to get his hands on Eli’s book so he can motivate his underlings to expand his empire. Unwilling to let this power fall into the wrong hands, Eli embarks on a dangerous journey that will test the limits of his faith.

SO WHY IS IT WORTH WATCHING?

Judging by the film’s box-office success, mainstream audiences appear to have enjoyed the Hughes’ bleak vision of a future where everything went wrong, but critics were left divided by the flick’s trope-heavy narrative and unapologetic religious elements. And while I’ll be the first to admit that The Book of Eli isn’t particularly subtle or original, I appreciate the film’s earnest execution of familiar ideas.

For starters, I’d like to address the religious elephant in the room, as I understand the hesitation that some folks (myself included) might have about watching something that sounds like Christian propaganda. Faith does indeed play a huge part in the narrative here, but I’d argue that the film is more about the power of stories than a specific religion. The entire point of Oldman’s character is that he needs a unifying narrative that he can take advantage of in order to manipulate others, while Eli ultimately chooses to deliver his gift to a community of scholars. In fact, the movie even makes a point of placing the Bible in between equally culturally important books like the Torah and Quran, which I think is pretty poignant for a flick inspired by exploitation cinema.

Sure, the film has its fair share of logical inconsistencies (ranging from the extent of Eli’s Daredevil superpowers to his impossibly small Braille Bible), but I think the film more than makes up for these nitpicks with a genuine passion for classic post-apocalyptic cinema. Several critics accused the film of being a knockoff of superior productions, but I’d argue that both Whitta and the Hughes knowingly crafted a loving pastiche of genre influences like Mad Max and A Boy and His Dog.

Lastly, it’s no surprise that the cast here absolutely kicks ass. Denzel plays the title role of a stoic badass perfectly (going so far as to train with Bruce Lee’s protégée in order to perform his own stunts) while Oldman effortlessly assumes a surprisingly subdued yet incredibly intimidating persona. Even Mila Kunis is remarkably charming here, though I wish the script had taken the time to develop these secondary characters a little further. And hey, did I mention that Tom Waits is in this?

AND WHAT MAKES IT HORROR ADJACENT?

Denzel’s very first interaction with another human being in this movie results in a gory fight scene culminating in a face-off against a masked brute wielding a chainsaw (which he presumably uses to butcher travelers before eating them), so I think it’s safe to say that this dog-eat-dog vision of America will likely appeal to horror fans.

From diseased cannibals to hyper-violent motorcycle gangs roaming the wasteland, there’s plenty of disturbing R-rated material here – which is even more impressive when you remember that this story revolves around the bible. And while there are a few too many references to sexual assault for my taste, even if it does make sense in-universe, the flick does a great job of immersing you in this post-nuclear nightmare.

The excessively depressing color palette and obvious green screen effects may take some viewers out of the experience, but the beat-up and lived-in sets and costume design do their best to bring this dead world to life – which might just be the scariest part of the experience.

Ultimately, I believe your enjoyment of The Book of Eli will largely depend on how willing you are to overlook some ham-fisted biblical references in order to enjoy some brutal post-apocalyptic shenanigans. And while I can’t really blame folks who’d rather not deal with that, I think it would be a shame to miss out on a genuinely engaging thrill-ride because of one minor detail.

With that in mind, I’m incredibly curious to see what Whitta and the Hughes Brothers have planned for the upcoming prequel series starring John Boyega…

There’s no understating the importance of a balanced media diet, and since bloody and disgusting entertainment isn’t exclusive to the horror genre, we’ve come up with Horror Adjacent – a recurring column where we recommend non-horror movies that horror fans might enjoy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.