“You Can Do This On a Human Being?” – Jack Pierce, the Forgotten Monster Makeup Pioneer

-

‘Trim Season’ Unrated Trailer – Acclaimed Movie Takes a Nightmarish Trip to a Marijuana Farm

-

“Pretty Little Liars: Summer School” Official Trailer Assembles the Final Girls and Starts Slashing

-

‘Trap’ – Official Trailer Previews a Wild New Horror Experience from M. Night Shyamalan

-

‘Transformers One’ Trailer – Chris Hemsworth Voices Optimus Prime in Brand New Animated Movie

In October 1966, a bed-ridden Jack Pierce gave one of his final interviews to Russ Jones for Monster Mania #1. Jones asked a number of rudimentary questions the magazine assumed fans would be most interested in, particularly Pierce’s time working for Universal Pictures. The famously waspish make-up artist was courteous in his responses, albeit without revealing too much beyond the ostensible replies; until Jones asked whether it was difficult working with Lon Chaney Jr. Pierce paused for a moment, before responding: “Yes and no. That’s all I can say.”

Janus Piccuola was born in Porto Heli, Greece, on May 5th, 1889, emigrating to the United States with his family in his teens and landing in Chicago, where he decided he’d like to try for a career as a professional baseball player. After making some headway in the semi-pro leagues, Piccuola travelled west, arriving in Los Angeles to try out as a professional, only to be met with the damning and final verdict that he was too short to make it as a pro.

Hurt by the rejection, Piccuola nevertheless set out to find employment elsewhere, meeting his future wife Blanche Craven and changing his name to Jack Pierce, a decision that would essentially ostracize Pierce from his family. At the time, the fledgling motion picture industry was in its early ascent and Pierce took a number of jobs, first as a theatre projectionist, then theatre-chain manager before ‘moving inside’ and trying his hand at a number of technical tasks behind the scenes, including stuntman, camera loader, assistant director, and bit-part actor.

It was during a stint working as an actor that Pierce decided the best way to guarantee regular work would be to create his own makeup, thereby ensuring he’d be able to play any character that a movie might call for. Fully aware that he lacked both aesthetic presence and stature of a matinee idol, Pierce looked to other actors who’d made a career of physical transformation for film roles. Lon Chaney at the time was fast becoming a household name as a master of makeup. The future ‘Man of a Thousand Faces’, along with Jack Dawn, who would eventually find fame as the makeup artist on The Wizard of Oz, inspired Pierce to develop his own skills while employed as a jobbing actor for Universal, Lasky’s Famous Players and Vitagraph.

In 1926, Fox Pictures went into production on the film The Monkey Talks, starring Jacques Lerner as a man who impersonates a primate. By this time, even though Pierce was still employed first-and-foremost as a camera man or assistant director, his skills as a makeup artist were well-known. With director Raoul Walsh struggling with the right look for the monkey effect, Pierce stepped in to help out, creating a simian-human makeup for star Jacques Lerner so richly detailed that it caught the attention of Carl Laemmle, the head of Universal Pictures.

Hiring Pierce on a full-time basis, Laemmle immediately set his new makeup artist to work on Universal’s next Lon Chaney vehicle, The Man Who Laughs, a Hollywood adaptation of the Victor Hugo novel which told the story of Gwynplain, the son of Lord put to death as a political enemy of King James II. As further punishment, Gwynplain’s face is carved into a permanent, wicked grin.

When Chaney vacated the role, the German actor Conrad Veidt stepped in, working closely with Pierce as the makeup artist formulated Gwynplain’s hideous grinning countenance. The achieved look undoubtedly caught the eye of Bob Kane who took the maniacal expression wholesale and applied it to the creation of comic supervillain The Joker, arch-nemesis of Batman.

With the advent of the first talking pictures, Veidt, concerned that his German accent would not play well in the new wave of Hollywood films, returned to his native country. In hindsight, it’s possible to posit that his work with Pierce could and perhaps should have continued in a series of horror films under the auspices of Carl Laemmle Jr. Pierce, however, continued in his new role, applying makeup on several films for Universal, though none were stretching him as an artist. Nonetheless, his expertise and meticulous application of makeup led to Pierce’s promotion to Universal’s head of makeup.

When Universal acquired the rights to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, young Laemmle Jr. sought out not Bela Lugosi, who’d recently achieved fame in the Broadway hit version, but a number up-and-coming stars including Paul Muni and John Wray, who’d previously starred in Universal’s smash All Quiet on the Western Front. Lugosi, desperate to play Dracula on film, lobbied hard for the role and was eventually cast, albeit for a fraction of the cost of more established stars.

As a stage actor, Lugosi had no interest in any makeup artist wishing to meddle with a character’s look that he felt he’d made his own, and so Pierce was reduced to styling the supporting characters. Despite Lugosi’s insistence on applying his own makeup, Pierce was able to create the green greasepaint for Count Dracula, and probably the black widow’s peak that would become synonymous with the character.

Dracula was an enormous success, and Universal immediately cast the net wide in search of further classic literature properties they could utilize for their burgeoning horror series. Securing the rights to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Universal immediately cast Bela Lugosi in the titular role, with Robert Florey in the director’s chair. However, test footage proved unsuccessful and with Florey’s screenplay portraying the Monster as a mute killing machine, Lugosi was said to have raged: “I was a star in my country and I will not be a scarecrow over here!” With the film in tatters, both director and star moved on to Murders in the Rue Morgue.

Meanwhile, James Whale, fresh from critical and commercial success as director of Waterloo Bridge, was offered a choice of projects by Laemmle Jr. He chose Frankenstein, since it was the only property that remotely interested him. He cast unknown journeyman actor, Boris Karloff, as the Monster. The film would mark Jack Pierce’s arrival as a makeup artist of true merit.

Following six months of research, Pierce put together a clay model to show Laemmle Jr. before commencing tests with Karloff: “It was a lot of hard work, trying to find ways and means, what can you do? Frankenstein wasn’t a doctor; he was a scientist, so he had to take the head and open it, and he took wires to rivet the head. I had to add the electrical outlets to connect electricity in here on the neck. I made it out of clay and put hair on it and took it in to Junior Laemmle’s office. He said, ‘you mean you can do this on a human being?’ I said, ‘positively’. He said, ‘all right we will go to the limit.’

Working for weeks with Karloff, Pierce created everything from scratch. A wig was made with a cotton roll on top, ‘to get the flatness and the circle that protrudes from the head’. The high forehead was built using cotton and collodion, while the heavy eyelid effect was the result of a putty specially designed by Pierce, who then applied a sky grey makeup he’d developed via the Max Factor Foundation. Pierce rounded out the look with black lipstick for a cadaverous appearance and the application of electrodes to the actor’s neck, the removal of which left scars that remained with Karloff for the rest of his life.

Pierce dressed the actor in black, and manipulated the clothing to give the impression that the Monster was eight feet tall; cutting the coat down so that Karloff’s arms looked longer than they actually were. He then padded out his shoes to add height. Years later, Pierce would remark: “I didn’t really teach him how to walk. Boris and I would talk, but the man is so wonderful, I think the greatest of them all as far as playing these parts.” The pièce de résistance, as far as the iconic look of the Monster is concerned, came at Pierce’s request; asking Karloff to remove a dental plate to create a gaunt, deathly visage.

Production of Frankenstein became a Herculean task for both Karloff and Pierce as, each day, Pierce would start from scratch, recreating the entire makeup effect. This would take several hours as he painstakingly reapplied makeup to Karloff’s face: then, following a full-day’s shooting, Karloff would be required to sit while Pierce began the lengthy removal procedure. On occasion this would test the patience of even the affable actor, who would head home in full makeup, spending an uncomfortable night sleeping with his head between two books and trying to ensure he didn’t roll onto his face. In the morning, Pierce would attempt to piece together what was left of the Monster makeup, but even this would take hours as he toiled to repair the damage.

Frankenstein opened in late-November 1931 to widespread critical and commercial acclaim, catapulting Boris Karloff to ‘instant’ stardom. However, despite a number of notices regarding the makeup, the name Jack Pierce remained in the shadows. The New Yorker’s review went so far as to address the Monster’s appearance, enthusing that ‘the makeup department has a triumph to its credit in the monster and there lie the thrills of the picture’. Unfortunately, there was no name to hand any plaudits to. Despite the Art Director, Recording Supervisor, even Scenario editor receiving a credit in the opening titles of Frankenstein, Jack Pierce remained a silent, unknown and, crucially, uncredited entity in Universal’s cycle of horror films.

___________________________________________________________________

In 1922, the English Archaeologist, Howard Carter, discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. Within a decade of the opening of the tomb, the deaths of ten people were directly or indirectly attributed to the mysterious ‘Curse of the Pharaohs’. The story was of particular interest to Carl Laemlle Jr., who subsequently commissioned screenwriter Richard Schayer to seek a novel and obtain the rights with a view to making a related horror film. When Schayer returned empty handed, Laemmle Jr. instructed the screenwriter to work on a story idea that could be turned into a script. Schayer set to work with writer Nina Wilcox Putnam and together they produced a treatment entitled Cagliostro. Suitably impressed, Laemmle employed John L. Balderston, who’d written the Bela Lugosi-starring stage play of Dracula and, more importantly had covered the opening of Tutankhamum’s tomb for New York World, to write a script, which he titled, The Mummy.

Once again, Jack Pierce, in his role as head of the makeup department, began preparations in earnest. By now Pierce was earning a reputation for having something of a short-fuse. He found the complaints of actors regarding his meticulous methods jarring and would respond to their sighs and mutterings in no uncertain terms. In Boris Karloff, however, Pierce discovered both a gentleman and a willing participant. It was just as well, too, for Pierce’s makeup procedure for The Mummy far outdid Frankenstein’s in terms of the sheer scale.

“The complete makeup, from the top of the head to the bottom of his feet took eight hours,” said Pierce. Starting with the bandages, which had to be secured with tape, Pierce then added a further set of bandages treated with acid and burned in an oven, and finished the costume with clay. The whole procedure was designed to give the effect of the bandages breaking and dust falling off as the mummified creature steps out of the sarcophagus. Despite the arduous process, this incarnation of the creature Im-Ho-Tep only appeared on screen in the opening moments of The Mummy.

Both Karloff and Pierce endured a simpler process for Im-Ho-Tep’s alter-ego, Ardath Bey. Utilizing a mixture of cotton, collodion and a sedimentary clay called Fuller’s earth, which wrinkled as it dried, Pierce applied the mixture to Karloff’s face to give the impression of a man many years older. In a rare moment of recognition, Pierce was subsequently awarded a Hollywood Filmograph for his makeup design an application.

Over the course of the decade, Jack Pierce continued to work on Universal’s burgeoning horror empire, often collaborating with his friend Boris Karloff in such notable fare as The Old Dark House, The Black Cat, The Night Key and Bride of Frankenstein, the latter famous for Pierce and director James Whale’s collaboration on the Bride’s iconic Marcel-wave hairstyle, based on Egyptian queen, Nefertiti.

Pierce prided himself on never using masks or appliances to accentuate his makeup creations, preferring instead to apply makeup in layers to build up the required look. He did however, acquiesce to the requirement for an appliance while creating the monstrous, hirsute look of The Wolf Man. Fortunately, in this case, he’d already run the hard yards in preparation for George Waggner’s werewolf tale, having originally conceiving the design for the abandoned film The Wolfman in 1932.

Three years later he was required to design a different version of the wolf makeup for Henry Hull in Werewolf of London. Hull, concerned that he wouldn’t be recognizable to the other characters – as opposed to the rather more apocryphal versions of the story that tell of Hull being unwilling to submit to hours in the makeup chair, or not wishing to obscure his face through sheer vanity – insisted upon a scaled-down version of Pierce’s original design.

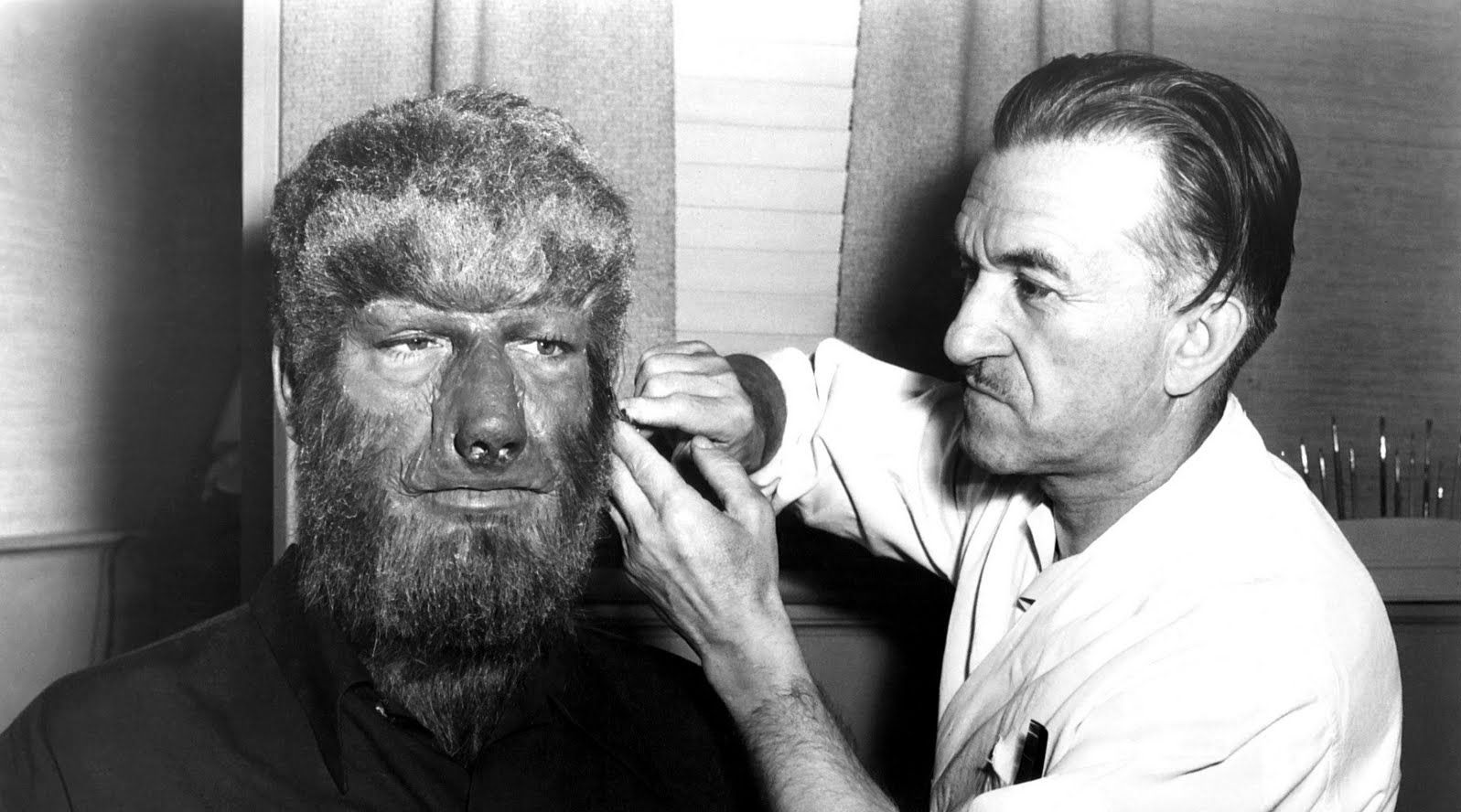

For The Wolf Man, Lon Chaney Jr. took the role of Lawrence Talbot, a man cursed to lycanthropy, and Pierce set to work on transforming the tall, imposing Chaney Jr. into a werewolf. Applying row-upon-row of yak hair, Pierce then singed and burned it to create the look of, “an animal that’s been out in the woods.” In his only concession to rubber prosthetics, Pierce would also attach a moulded nose, explaining that it was either that or he would need to “model the nose every day, which would have taken too long.” As it was, the entire process took several hours to apply, which Pierce painstakingly began from scratch every single day.

While Pierce’s relationship with Boris Karloff was cordial, even friendly, Lon Chaney Jr. was a rather less genial character and the two reportedly clashed often, with Chaney Jr. complaining that Pierce would intentionally burn him with the curling iron used to singe the yak hair on his face. On one occasion, the two allegedly almost came to blows. Nonetheless, they continued to work together on a number of Universal films, including The Ghost of Frankenstein, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man and House of Dracula, with Chaney Jr. once sending a signed photo to Pierce with the following inscription:

To the greatest goddamned sadist in the world – L.C

___________________________________________________________________

By the mid-1940s technology was beginning to catch up with Jack Pierce. His stubborn refusal to use appliances rankled with the studio, who were keen to save time and budget in pursuit of greater profit. Pierce, always an artist first, continued to forge his own creative path, creating yet another iconic look for Claude Rains in a remake of Phantom of the Opera. When Universal merged with International Pictures in 1945, however, Pierce’s days were numbered and Bud Westmore was given the job in place of the 57-year-old. Westmore, a student of a more contemporary approach to makeup effects and a keen advocate of foam latex and masks for creature creations, took over and Pierce was quietly fired. During his time working for Universal, Unfortunately for Pierce, he had never signed a contract with the studio; such was his loyalty, and he thus received little more than a handshake for 30 years’ service.

The makeup artist saw out the remainder of his career working in a freelance capacity on B-pictures and occasionally on television shows. His last significant work was on a successful TV series about a talking horse, Mr. Ed, created by Pierce’s old friend from Universal, Arthur Lubin. Although his creations continued to be utilized until the mid-50s, by the time Pierce finally retired, the horror film industry had moved on and the public no longer clamored to see his monsters. Hammer Productions in the UK began their own series of films at the end of the 1950s based on the classic monsters, but Universal retained the rights to Pierce’s designs and refused to let Hammer impinge on their copyright.

Jack Pierce died from uremia on the 19th July 1968. At the time of his death, Pierce was living in near poverty, forgotten by the industry and genre that he’d helped to build. He was interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California with only a handful of people attending his funeral.

It seems profoundly sad that the name Jack Pierce is, even among horror fans to some degree, all but forgotten. Yet, when one conjures the image of Frankenstein’s Monster, it is without doubt that of the hulking Karloff, looming into view, flat-headed and sunken cheeked, bolts protruding from his neck. The same might be said of both Dracula, The Mummy and The Wolf Man, so ingrained on our conscious are Pierce’s creations. Still, their creator remains a mystery to most, despite inspiring a number of the twentieth century’s greatest makeup and special effects artists. Rick Baker and Tom Savini, for example, cite Pierce as a defining influence on their careers.

It’s entirely possible that Jack Pierce’s alleged reticence to move with the times and incorporate new technologies and techniques ultimately destroyed his career. Yet, this was the very same man who, when asked how makeup would evolve, replied with the following: “Looking forward, the future holds great possibilities. Makeup is only beginning to reach its artistic stride.”

How right he was.

Editorials

‘Amityville Karen’ Is a Weak Update on ‘Serial Mom’ [Amityville IP]

Twice a month Joe Lipsett will dissect a new Amityville Horror film to explore how the “franchise” has evolved in increasingly ludicrous directions. This is “The Amityville IP.”

A bizarre recurring issue with the Amityville “franchise” is that the films tend to be needlessly complicated. Back in the day, the first sequels moved away from the original film’s religious-themed haunted house storyline in favor of streamlined, easily digestible concepts such as “haunted lamp” or “haunted mirror.”

As the budgets plummeted and indie filmmakers capitalized on the brand’s notoriety, it seems the wrong lessons were learned. Runtimes have ballooned past the 90-minute mark and the narratives are often saggy and unfocused.

Both issues are clearly on display in Amityville Karen (2022), a film that starts off rough, but promising, and ends with a confused whimper.

The promise is embodied by the tinge of self-awareness in Julie Anne Prescott (The Amityville Harvest)’s screenplay, namely the nods to John Waters’ classic 1994 satire, Serial Mom. In that film, Beverly Sutphin (an iconic Kathleen Turner) is a bored, white suburban woman who punished individuals who didn’t adhere to her rigid definition of social norms. What is “Karen” but a contemporary equivalent?

In director/actor Shawn C. Phillips’ film, Karen (Lauren Francesca) is perpetually outraged. In her introductory scenes, she makes derogatory comments about immigrants, calls a female neighbor a whore, and nearly runs over a family blocking her driveway. She’s a broad, albeit familiar persona; in many ways, she’s less of a character than a caricature (the living embodiment of the name/meme).

These early scenes also establish a fairly straightforward plot. Karen is a code enforcement officer with plans to shut down a local winery she has deemed disgusting. They’re preparing for a big wine tasting event, which Karen plans to ruin, but when she steals a bottle of cursed Amityville wine, it activates her murderous rage and goes on a killing spree.

Simple enough, right?

Unfortunately, Amityville Karen spins out of control almost immediately. At nearly every opportunity, Prescott’s screenplay eschews narrative cohesion and simplicity in favour of overly complicated developments and extraneous characters.

Take, for example, the wine tasting event. The film spends an entire day at the winery: first during the day as a band plays, then at a beer tasting (???) that night. Neither of these events are the much touted wine-tasting, however; that is actually a private party happening later at server Troy (James Duval)’s house.

Weirdly though, following Troy’s death, the party’s location is inexplicably moved to Karen’s house for the climax of the film, but the whole event plays like an afterthought and features a litany of characters we have never met before.

This is a recurring issue throughout Amityville Karen, which frequently introduces random characters for a scene or two. Karen is typically absent from these scenes, which makes them feel superfluous and unimportant. When the actress is on screen, the film has an anchor and a narrative drive. The scenes without her, on the other hand, feel bloated and directionless (blame editor Will Collazo Jr., who allows these moments to play out interminably).

Compounding the issue is that the majority of the actors are non-professionals and these scenes play like poorly performed improv. The result is long, dull stretches that features bad actors talking over each other, repeating the same dialogue, and generally doing nothing to advance the narrative or develop the characters.

While Karen is one-note and histrionic throughout the film, at least there’s a game willingness to Francesca’s performance. It feels appropriately campy, though as the film progresses, it becomes less and less clear if Amityville Karen is actually in on the joke.

Like Amityville Cop before it, there are legit moments of self-awareness (the Serial Mom references), but it’s never certain how much of this is intentional. Take, for example, Karen’s glaringly obvious wig: it unconvincingly fails to conceal Francesca’s dark hair in the back, but is that on purpose or is it a technical error?

Ultimately there’s very little to recommend about Amityville Karen. Despite the game performance by its lead and the gentle homages to Serial Mom’s prank call and white shoes after Labor Day jokes, the never-ending improv scenes by non-professional actors, the bloated screenplay, and the jittery direction by Phillips doom the production.

Clocking in at an insufferable 100 minutes, Amityville Karen ranks among the worst of the “franchise,” coming in just above Phillips’ other entry, Amityville Hex.

The Amityville IP Awards go to…

- Favorite Subplot: In the afternoon event, there’s a self-proclaimed “hot boy summer” band consisting of burly, bare-chested men who play instruments that don’t make sound (for real, there’s no audio of their music). There’s also a scheming manager who is skimming money off the top, but that’s not as funny.

- Least Favorite Subplot: For reasons that don’t make any sense, the winery is also hosting a beer tasting which means there are multiple scenes of bartender Alex (Phillips) hoping to bring in women, mistakenly conflating a pint of beer with a “flight,” and goading never before seen characters to chug. One of them describes the beer as such: “It looks like a vampire menstruating in a cup” (it’s a gold-colored IPA for the record, so…no).

- Amityville Connection: The rationale for Karen’s killing spree is attributed to Amityville wine, whose crop was planted on cursed land. This is explained by vino groupie Annie (Jennifer Nangle) to band groupie Bianca (Lilith Stabs). It’s a lot of nonsense, but it is kind of fun when Annie claims to “taste the damnation in every sip.”

- Neverending Story: The film ends with an exhaustive FIVE MINUTE montage of Phillips’ friends posing as reporters in front of terrible green screen discussing the “killer Karen” story. My kingdom for Amityville’s regular reporter Peter Sommers (John R. Walker) to return!

- Best Line 1: Winery owner Dallas (Derek K. Long), describing Karen: “She’s like a walking constipation with a hemorrhoid”

- Best Line 2: Karen, when a half-naked, bleeding woman emerges from her closet: “Is this a dream? This dream is offensive! Stop being naked!”

- Best Line 3: Troy, upset that Karen may cancel the wine tasting at his house: “I sanded that deck for days. You don’t just sand a deck for days and then let someone shit on it!”

- Worst Death: Karen kills a Pool Boy (Dustin Clingan) after pushing his head under water for literally 1 second, then screeches “This is for putting leaves on my plants!”

- Least Clear Death(s): The bodies of a phone salesman and a barista are seen in Karen’s closet and bathroom, though how she killed them are completely unclear

- Best Death: Troy is stabbed in the back of the neck with a bottle opener, which Karen proceeds to crank

- Wannabe Lynch: After drinking the wine, Karen is confronted in her home by Barnaby (Carl Solomon) who makes her sign a crude, hand drawn blood contract and informs her that her belly is “pregnant from the juices of his grapes.” Phillips films Barnaby like a cross between the unhoused man in Mulholland Drive and the Mystery Man in Lost Highway. It’s interesting, even if the character makes absolutely no sense.

- Single Image Summary: At one point, a random man emerges from the shower in a towel and excitedly poops himself. This sequence perfectly encapsulates the experience of watching Amityville Karen.

- Pray for Joe: Many of these folks will be back in Amityville Shark House and Amityville Webcam, so we’re not out of the woods yet…

Next time: let’s hope Christmas comes early with 2022’s Amityville Christmas Vacation. It was the winner of Fangoria’s Best Amityville award, after all!

You must be logged in to post a comment.