Editorials

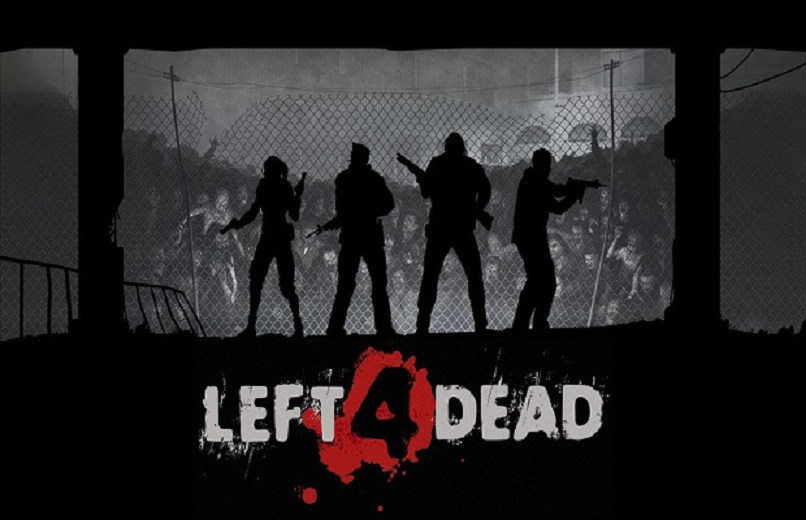

No Mercy! Celebrating the 10th Anniversary of ‘Left 4 Dead’

To anyone who can hear this: Proceed to Mercy Hospital for evacuation. I repeat: Proceed to Mercy Hospital for evacuation.

I can’t recall how many times I’ve heard this over the past 10 years. Left 4 Dead first showed up in my life as merely a dream: my PC would barely showcase the main menu without taking me back to the desktop with a crash message. And, perhaps without realizing it, the game became the reason why I upgraded graphics card in order to play it. I’ve never looked back since, clocking over hundreds of hours on it.

We could discuss many of the aspects why it became such a huge game, how it set the foundations of the sequel or perhaps dive into its ridiculously large modding scene, but for its 10th anniversary, I want to talk about how it all began. And, in this case, that means remembering the first campaign of the game: No Mercy.

A chopper flies through a desolated city while a group of survivors prepares for the night of their lives. The biker Francis, the college student Zoey, the Vietnam veteran Bill, and the Junior Systems Analyst named Louis gather together, grabbing their weapon of choice and a medkit. Following the flying message, they start chasing the helicopter in the midst of a zombie outbreak shooting everything in sight, and quickly learning there is friendly fire enabled for default.

You know how the stereotype of a zombie had largely been to portray them as slow-moving beings, often being more on the dumb side than anything? Well, in Left 4 Dead, zombies could run. And folks, let me tell you: they run fast.

We are talking about 28 Days Later level of undead aggressiveness. Hordes await for you in every street, expecting for the slight miscalculation from your part to go forth. Shooting a car and making the alarm go off might attract hundreds of them in a matter of seconds, along with causing your teammates to shout at you over the microphone. And zombies can also climb over fences and pretty much anything that gets on their way. Once they spot you, you better be ready to either confront or run, as they will stop at nothing to get at you. Don’t expect any bites, though. They just hit you furiously until you’re gone for good.

No Mercy isn’t just the beginning of the story for these survivors, but also for the players themselves into this world, and more importantly, its pacing. Left 4 Dead is a quick, often unmerciful game, in which cooperation is key to success and a mandatory element in high difficulties. Learning the best way to quickly get to the checkpoint, marked in the game as safe houses where one can take some rest, resupply, heal their wounds and, well, finally go to the bathroom, appears as a natural instinct after the first few hours. Same goes with weapons, looking for the best “builds” alongside teammates, like carrying two shotguns to open a path ahead while the rest focus on taking down the special infected, such as a Boomer waiting to jump on the group or a Smoker, preparing to capture a wandering survivor.

And everything surrounded it carried a lot of style back then, which has been translated almost perfectly (more on that later) upon the sequel. The premise behind the game makes it look like an ongoing story divided in movies. The film grain might help, too, but it’s the iconic posters that helped to shape that general feeling. Additionally, the AI system behind the game, which takes care of infected or supplies spawns depending on the party status, goes by the name of The Director. This virtual entity is the scenographer who, depending on how things are going in a campaign, will make the team’s lives harder or a bit easier, depending on the difficulty of course.

But the biggest element that didn’t manage to endure is Left 4 Dead: 2 is, plain and simple, fear. The way level design introduced itself in every corner of the campaigns made for claustrophobic escapes. One could be scared to open a door inside a building as much as being alone on an illuminated street with plenty of room to spare. The uncertainty, and how aggressive the game could become in a matter of seconds just when you were enjoying a moment of respite made the game feel unique from similar experiences such as Killing Floor or No More Room In Hell.

There’s one time I would never forget in my passing through No Mercy. During an online match, we reached the hospital with more than a few scratches, but the way out was almost there. We could feel it. Thing is, we had to wait for the elevator to pick us up in order to get to the roof, where the chopper was set to arrive soon. And that meant hordes of undead were just waiting for us to press the button.

To those unfamiliar with No Mercy Hospital, that’s the place where the latter half of the campaign takes place. Just in the end of the second chapter, right after fighting your way through the sewers system, you meet the colossal building. There is a vast number of stairs and floors that you need to cross in order to reach to said elevator, which is your only ticket to get to the roof. It’s an obscure scenario, filled with pitch dark rooms and undead patients still wearing their robes. And waiting for the elevator takes forever, demanding a serious defense plan to hold your ground.

We pressed the button and they started coming. Shotgun shells bouncing on the floor, flashes of light after each shot and blinking lights illuminated the place. There were blood splatters everywhere, and the marching wave of enemies seemed like it would never cease. It proved to be too much for my team, and we were quickly beaten down, one by one. I was the last person standing.

Matchmaking had made Louis my selected character for this run, and I discovered something I hadn’t seen in the years since first playing the game. I took refuge in a room, barely standing anymore due to my low health. Zoey lifted me up when I fell minutes prior, but I could barely see. Pictures of a doctor bed and medical tools in black and white surrounded my sight. And in that moment, Louis started humming a song in a low tone. While I couldn’t see him, I could fear his sweat, his hands shaking. The sound of yet another horde could be heard again, getting closer and closer, until they found him.

As I play through No Mercy once more to remember these moments, I get surprised at how it managed to withstand the passage of time. Zombies still managed to scare me. Hearing the music that indicated a Tank was about to attack us woke up all my senses. And the hospital was still there, just as I remembered it, waiting for me and my group to get to the chopper, with the illusion that it was the one-way ticket out to safety from this nightmare.

Left 4 Dead is now 10 years old, and during that time, thousands of stories were created seamlessly. Anecdotes with friends, late night LAN parties, and hearing Francis’ voice lines complaining about pretty much anything will remain in our minds forever. But it’s valuable to remember how it managed to create a B-movie experience that was not only fun and challenging but also scary, even with company.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.