Editorials

[Editorial] As Horror Franchise “Remakes” Evolve, Let’s Talk About How to Classify Them

Back in November, director Fede Alvarez tweeted that his 2013 version of Evil Dead “continues the first [The Evil Dead],” adding, “The coincidences on events between the first film and [the 2013 film] are not coincidences, but more like dark fate created by the evil book.” There were hints, of course—the car, the Bruce Campbell stinger cameo—but almost everyone referred to it as a “remake”. In fact, a simple Google search of “best horror remakes” puts Evil Dead at the very top of the most popular. The point being made here? If we are to take Alvarez’s word, and why wouldn’t we, it’s clear that the word “remake” is too simple a term to describe the multitude of ways the horror genre returns to the well of classics.

In Scream 4, Hayden Panettiere’s Kirby rattles off fifteen different modern movies in response to Ghostface’s question regarding “the remake of the groundbreaking horror movie in which the vill…” She cuts him off to answer, and this particular back-and-forth is likely a favorite moment for anyone who enjoyed the film; it shows how savvy Kirby is as well as allowing Craven and co. to add another dose of meta-commentary about the glut of horror remakes we’ve been subjected to in the last decade-and-a-half. They’re so common now, that it almost feels as if every horror property has been drained dry enough that studios are now finding new ways to remake, reboot, reimagine, refresh, and revive horror. I’m not saying it’s a problem. The more the merrier, especially when they’re good!

We do, however, have a bit of a problem when it comes to how we define or categorize these movies. “Sequel” obviously doesn’t quite do the trick, but lately “remake”, “reboot”, and “reimagining” are also becoming problematic phrases. We simply can’t seem to agree, can we?

I suggest we do a bit of our own reimagining when it comes to horror nomenclature. I offer four unique and identifiable types of horror movie refresh categories: REMAKE, REBOOT, LEGACYQUEL and RE-SEQUEL. Before I tackle them, I want to situate my argument as a locus for discourse rather than an all-out diatribe. These terms are in flux, and it should be fun to try to discuss ways these movies land within a category.

REMAKE

It’s the most obvious of our terms, and certainly the version that’s been around longest. Films of every genre have been remade starting with 1903’s The Great Train Robbery. A remake takes an existing film that deserves a second crack, a new audience, or a combination of both and presents a modern retelling of the primary film. The easiest of these to argue for are American remakes of foreign films. J-Horror pictures like The Ring and The Grudge are the most financially successful of their genre, but films such as Let Me In, Silent House, and Quarantine also received a red, white, and blue coat of paint to varying degrees of success.

But the 2000s were a hotbed for homegrown horror remakes. Dawn of the Dead, The Hills Have Eyes, Amityville Horror, Last House on the Left, My Bloody Valentine, When A Stranger Calls, Prom Night, Black Christmas, House of Wax, The Fog, and Piranha are all straight-up remakes. Each of these movies features relatively similar plot and characters, and gives them a modern polish with an occasional injection of contemporary themes. All but two of these films prompted a direct sequel.

Perhaps the strangest of all is the 1998, Gus Van Sant directed shot-for-unnecessary-shot remake of Psycho. The director called it “an experiment,” but you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who finds the results in the least bit interesting. The original is a near-perfect horror classic, and Van Sant’s Psycho is perhaps the poster child for unnecessary remakes.

REBOOT

You might have noticed a few big-name franchises absent from the remakes category above. This is no accident. Rather, I find that a second appropriate category is the franchise “reboot.”

Batman Begins is hardly a horror movie. (Though the entire theme of the film is “fear”—perhaps the center of the Batman/horror venn diagram is bigger than most people assume.) It does, however, establish the parameters for a proper reboot. A reboot effectively pulls the plug on an existing franchise, uses the same machinery (characters, settings, themes) and resets the canonical timeline. The intention of a reboot is to set a franchise on a different, alternate path, in hopes to re-energize a fanbase and create more sequels. I remember advertisements for Batman Begins that were intentionally vague about the film being a remake. In fact, I believe that if audiences thought Begins was a prequel to the 1989 Batman, Warner Brothers was more than comfortable with that misconception. As it turns out, the film rebooted Batman to extreme financial and critical acclaim, and it spawned one of the most beloved sequels of all time.

2003’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre actually did it first. The plot follows a similar trajectory to the original film in the way a traditional remake does, but TCM was always intended to give the franchise a new beginning (not to be confused with Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, a prequel to the 2003 film.) The TCM franchise is a bit of an anomaly that includes three sequels, two prequels, a reboot, and a film we’ll talk about later in this article. The 2003 film didn’t birth several sequels, but for its efforts, it’s absolutely a reboot.

In 2007, Rob Zombie’s polarizing Halloween was frequently referred to as a “reimagining” of John Carpenter’s original vision, most likely as a result of remake fatigue. By all means, however, it’s a reboot. Zombie has stated that he envisions his film in three acts; the first being Young Michael Myers’s backstory, the second being his time at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, and the third seeing his return to Haddonfield—during which we witness a consolidated version of the original film. Zombie’s new Halloween, complete with the filmmaker’s occasionally extreme idiosyncrasies, is a unique take on the remake formula. More specifically, though, his film received a sequel, and even warranted talks of an unmade third installment, positioning 2007’s Halloween as a reboot.

Two other movies fit squarely in this category, despite the fact that they were ultimately unsuccessful at kickstarting a line of sequels: 2009’s Friday the 13th and 2010’s A Nightmare on Elm Street. The former is of particular interest because there isn’t a singular source movie that gets the remake treatment. Rather, Friday 2009 remixes elements of the first four films in the franchise. It’s certainly not a sequel, and the events of the original film are relegated to mere exposition. Thus, we can’t call it a remake at all. The only thing left to call it is a reboot. 2010’s Elm Street actually hews closely to its source material, even naming its central protagonist Nancy. Without the legendary Robert Englund as Freddy, though, the film couldn’t recreate the tone and magic of the original. It was critically reviled, and despite enough box office success to at least get people to consider a sequel, hardly anything developed.

This category has been the least active as of late, especially when it comes to the horror genre. There are astronomically more one-off horror films than franchises, which makes for fewer reboot possibilities. Needless to say, we’re in dire need of both a Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street reboot… again.

LEGACYQUEL

I began with Evil Dead and Scream 4, because they highlight a new, alternative take on the remake formula. Legacy-Sequels or legacyquels are a new phenomenon, and are not really remakes at all. The term was coined in a Screen Rant article in 2015. For all intents and purposes, a legacyquel is an in-continuity, canonical sequel to the film or films in the series that precede it. The twist is that the plot of the new movie is strikingly, and often purposefully, similar to the first one. The filmmakers hope that the audience’s love of the plot, the “legacy” of the first one, will add additional appreciation to the new film. Legacyquel isn’t an industry term yet, but these obvious nostalgia cash-in attempts are far from accidents.

Jurassic World is easily the most famous and most profitable horror legacyquel. The simple plot, “cloned dinosaurs escape and attack humans”, is given a steroid shot of CGI, star power, and easter eggs. It’s the same plot, again, twenty years later.

If Jurassic World is the biggest legacyquel, Evil Dead is certainly the most beloved. I’ve seen it atop several “best horror remake” lists, and five years later we’re still talking about the movie. The original The Evil Dead is the quintessential cabin-in-the-woods horror flick. Fede Alvarez’s 2013 film removes the humor of the original trilogy, injects a relevant and modern drug abuse and recovery theme, and amplifies the scares, all while maintaining the simplistic plot that made the first two Evil Dead films work so well. Up until November, we were all willing to call it a remake, but the idea that the Necronomicon can manifest repeated haunts and events adds a layer of depth and intrigue to the franchise. Turns out one of the best remakes, is actually one of the best sequels in a franchise rife with mythology.

Scream 4 might be better than you remember, and it’s because it knows it’s a legacyquel. Not only is the relatively simple whodunnit plot reimagined for a modern audience, but the meta plot, in which the teen characters are literally attempting to recreate the events of the first film, drips with irony and intrigue. Of course, we know Scream 4 is a sequel, but the film’s satirical riff on remakes is better than any of the other obvious attempts to lambaste the remake format. Scream 4 is actually scary, it evokes the tone of the original, and it properly shines a blinding light on remakes.

Curse of Chucky is one of the better legacyquels, in that it resets the tone of the franchise to its scary roots. After the original Child’s Play films, the mystery of whether the doll is actually a killer is dropped in favor of essentially making him the central plot motivator in Bride and Seed of Chucky. The plot of Curse of Chucky doesn’t follow the original, but its tone and intent are a return to form. There’s a central mystery, and the driving force of the film is terror rather than comedy. Personally, I wondered if the movie was a total reboot until the third act revealed the same old Chucky we know and love.

RE-QUEL

The latest attempt to breath new life into a dormant franchise is the re-quel. Films of this ilk blend features of reboots and legacyquels. The idea is that, rather than blowing up an entire continuity and starting fresh a la a reboot, a legacyquel maintains a franchise’s continuity, but takes place within a canonical timeline rather than at the end of it. It’s such a new idea, that I can only identify three instances.

The worst example is undoubtedly 2013’s Texas Chainsaw (3D). The film was heavily advertised as a direct sequel to the original film, but if the idea was to create a new timeline, it didn’t work. Only four years later, the franchise produced an even less successful direct-to-digital prequel.

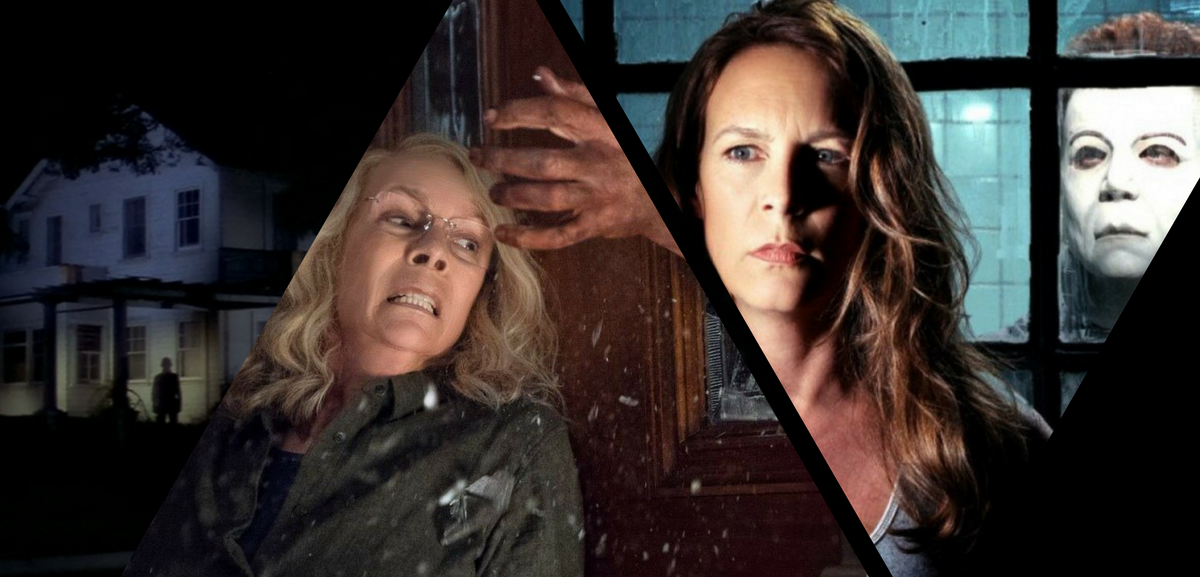

The Halloween franchise has famously done it twice. Forgive the recap, but in 1998, Halloween: H20 eschewed the plots of Halloween 4-6, refocusing on Laurie Strode, and serving as the third film in her story. Last year David Gordon Green’s Halloween did it again, this time taking the timeline back one movie prior; a direct sequel to the 1978 original. This has been discussed ad nauseum, but I highlight it here, because the fact that it’s happened twice in a franchise (that also received the reboot treatment) is unprecedented. Reviews for the film were mixed, but generally positive, and it’s only a matter of time before re-quels start popping up in other franchises.

These terms—remake, reboot, legacyquel, and re-quel—are only my best attempt to arrange a subgenre of horror film too vast to fully categorize. But it’s a start. There are, of course, films I’ve listed in certain categories that share elements of others. In some ways; Halloween is a legacyquel, Curse of Chucky feels like a reboot. I’ve also made some glaring omissions. What about prequels? What the hell is Evil Dead II? Ultimately, we’re talking about rhetoric. What these films give us is an opportunity to talk about how they and their directors, writers, and producers make designs on us. If we can expedite the process of organizing these films, and agree upon the nomenclature, we can skip ahead to critiquing more effectively, and perhaps find new ways to appreciate a type of horror movie that’s often criticized for its lack of originality.

Editorials

‘Amityville Karen’ Is a Weak Update on ‘Serial Mom’ [Amityville IP]

Twice a month Joe Lipsett will dissect a new Amityville Horror film to explore how the “franchise” has evolved in increasingly ludicrous directions. This is “The Amityville IP.”

A bizarre recurring issue with the Amityville “franchise” is that the films tend to be needlessly complicated. Back in the day, the first sequels moved away from the original film’s religious-themed haunted house storyline in favor of streamlined, easily digestible concepts such as “haunted lamp” or “haunted mirror.”

As the budgets plummeted and indie filmmakers capitalized on the brand’s notoriety, it seems the wrong lessons were learned. Runtimes have ballooned past the 90-minute mark and the narratives are often saggy and unfocused.

Both issues are clearly on display in Amityville Karen (2022), a film that starts off rough, but promising, and ends with a confused whimper.

The promise is embodied by the tinge of self-awareness in Julie Anne Prescott (The Amityville Harvest)’s screenplay, namely the nods to John Waters’ classic 1994 satire, Serial Mom. In that film, Beverly Sutphin (an iconic Kathleen Turner) is a bored, white suburban woman who punished individuals who didn’t adhere to her rigid definition of social norms. What is “Karen” but a contemporary equivalent?

In director/actor Shawn C. Phillips’ film, Karen (Lauren Francesca) is perpetually outraged. In her introductory scenes, she makes derogatory comments about immigrants, calls a female neighbor a whore, and nearly runs over a family blocking her driveway. She’s a broad, albeit familiar persona; in many ways, she’s less of a character than a caricature (the living embodiment of the name/meme).

These early scenes also establish a fairly straightforward plot. Karen is a code enforcement officer with plans to shut down a local winery she has deemed disgusting. They’re preparing for a big wine tasting event, which Karen plans to ruin, but when she steals a bottle of cursed Amityville wine, it activates her murderous rage and goes on a killing spree.

Simple enough, right?

Unfortunately, Amityville Karen spins out of control almost immediately. At nearly every opportunity, Prescott’s screenplay eschews narrative cohesion and simplicity in favour of overly complicated developments and extraneous characters.

Take, for example, the wine tasting event. The film spends an entire day at the winery: first during the day as a band plays, then at a beer tasting (???) that night. Neither of these events are the much touted wine-tasting, however; that is actually a private party happening later at server Troy (James Duval)’s house.

Weirdly though, following Troy’s death, the party’s location is inexplicably moved to Karen’s house for the climax of the film, but the whole event plays like an afterthought and features a litany of characters we have never met before.

This is a recurring issue throughout Amityville Karen, which frequently introduces random characters for a scene or two. Karen is typically absent from these scenes, which makes them feel superfluous and unimportant. When the actress is on screen, the film has an anchor and a narrative drive. The scenes without her, on the other hand, feel bloated and directionless (blame editor Will Collazo Jr., who allows these moments to play out interminably).

Compounding the issue is that the majority of the actors are non-professionals and these scenes play like poorly performed improv. The result is long, dull stretches that features bad actors talking over each other, repeating the same dialogue, and generally doing nothing to advance the narrative or develop the characters.

While Karen is one-note and histrionic throughout the film, at least there’s a game willingness to Francesca’s performance. It feels appropriately campy, though as the film progresses, it becomes less and less clear if Amityville Karen is actually in on the joke.

Like Amityville Cop before it, there are legit moments of self-awareness (the Serial Mom references), but it’s never certain how much of this is intentional. Take, for example, Karen’s glaringly obvious wig: it unconvincingly fails to conceal Francesca’s dark hair in the back, but is that on purpose or is it a technical error?

Ultimately there’s very little to recommend about Amityville Karen. Despite the game performance by its lead and the gentle homages to Serial Mom’s prank call and white shoes after Labor Day jokes, the never-ending improv scenes by non-professional actors, the bloated screenplay, and the jittery direction by Phillips doom the production.

Clocking in at an insufferable 100 minutes, Amityville Karen ranks among the worst of the “franchise,” coming in just above Phillips’ other entry, Amityville Hex.

The Amityville IP Awards go to…

- Favorite Subplot: In the afternoon event, there’s a self-proclaimed “hot boy summer” band consisting of burly, bare-chested men who play instruments that don’t make sound (for real, there’s no audio of their music). There’s also a scheming manager who is skimming money off the top, but that’s not as funny.

- Least Favorite Subplot: For reasons that don’t make any sense, the winery is also hosting a beer tasting which means there are multiple scenes of bartender Alex (Phillips) hoping to bring in women, mistakenly conflating a pint of beer with a “flight,” and goading never before seen characters to chug. One of them describes the beer as such: “It looks like a vampire menstruating in a cup” (it’s a gold-colored IPA for the record, so…no).

- Amityville Connection: The rationale for Karen’s killing spree is attributed to Amityville wine, whose crop was planted on cursed land. This is explained by vino groupie Annie (Jennifer Nangle) to band groupie Bianca (Lilith Stabs). It’s a lot of nonsense, but it is kind of fun when Annie claims to “taste the damnation in every sip.”

- Neverending Story: The film ends with an exhaustive FIVE MINUTE montage of Phillips’ friends posing as reporters in front of terrible green screen discussing the “killer Karen” story. My kingdom for Amityville’s regular reporter Peter Sommers (John R. Walker) to return!

- Best Line 1: Winery owner Dallas (Derek K. Long), describing Karen: “She’s like a walking constipation with a hemorrhoid”

- Best Line 2: Karen, when a half-naked, bleeding woman emerges from her closet: “Is this a dream? This dream is offensive! Stop being naked!”

- Best Line 3: Troy, upset that Karen may cancel the wine tasting at his house: “I sanded that deck for days. You don’t just sand a deck for days and then let someone shit on it!”

- Worst Death: Karen kills a Pool Boy (Dustin Clingan) after pushing his head under water for literally 1 second, then screeches “This is for putting leaves on my plants!”

- Least Clear Death(s): The bodies of a phone salesman and a barista are seen in Karen’s closet and bathroom, though how she killed them are completely unclear

- Best Death: Troy is stabbed in the back of the neck with a bottle opener, which Karen proceeds to crank

- Wannabe Lynch: After drinking the wine, Karen is confronted in her home by Barnaby (Carl Solomon) who makes her sign a crude, hand drawn blood contract and informs her that her belly is “pregnant from the juices of his grapes.” Phillips films Barnaby like a cross between the unhoused man in Mulholland Drive and the Mystery Man in Lost Highway. It’s interesting, even if the character makes absolutely no sense.

- Single Image Summary: At one point, a random man emerges from the shower in a towel and excitedly poops himself. This sequence perfectly encapsulates the experience of watching Amityville Karen.

- Pray for Joe: Many of these folks will be back in Amityville Shark House and Amityville Webcam, so we’re not out of the woods yet…

Next time: let’s hope Christmas comes early with 2022’s Amityville Christmas Vacation. It was the winner of Fangoria’s Best Amityville award, after all!

You must be logged in to post a comment.