Books

Scholastic Trauma: The Timeless Horror of the ‘Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark’ Series

If you were to ask me what the highlight of elementary school was, my immediate first response would be the Scholastic Book Fair.

The joy of the Scholastic Book Fair is something near-indescribable to anyone who didn’t experience it during their elementary years, but it’s nonetheless an event that can appeal to just about anybody. The Scholastic Book Fair is exactly what it sounds like; a fair composed of a high variety of entertaining books of all reading levels for elementary kids to bug their parents out of $20-$40 for. It is something akin to holiday shopping for kids in grade school and it was a helpful introduction to various types of literature that I personally might not have sought out otherwise. Acquiring literature through the lens of a fun school fair felt so much more rewarding than if a teacher just handed them out to us.

However, it was very unlikely that teachers would hand out any of the “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” books, despite their seal of Scholastic approval.

The “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” series, a trilogy of children’s horror books released over a time span of 10 years from 1981 to 1991, were notoriously difficult to get through the Scholastic system. A collection of folklore tales retold by Alvin Schwartz, “Scary Stories” differed heavily from its more child-friendly counterparts at Scholastic thanks to its short and often cynical and terrifying short stories. The stories served as adaptations of classic folklore tales geared to a modern (80s) audience with modern fears and belief systems. Famous stories like “The Hook”, “Killer in the Backseat”, “The Hitchhiker”, and so on get a short, but oh so sweet update that make up the bulk of the books. The stories themselves are simple and easy to read, being children’s stories after all, but it’s not the technical form of the writing that has stuck with Gen-X and millennial readers for generations.

The most definitive feature of “Scary Stories” is the terrifying illustrative genius of Stephen Gammell.

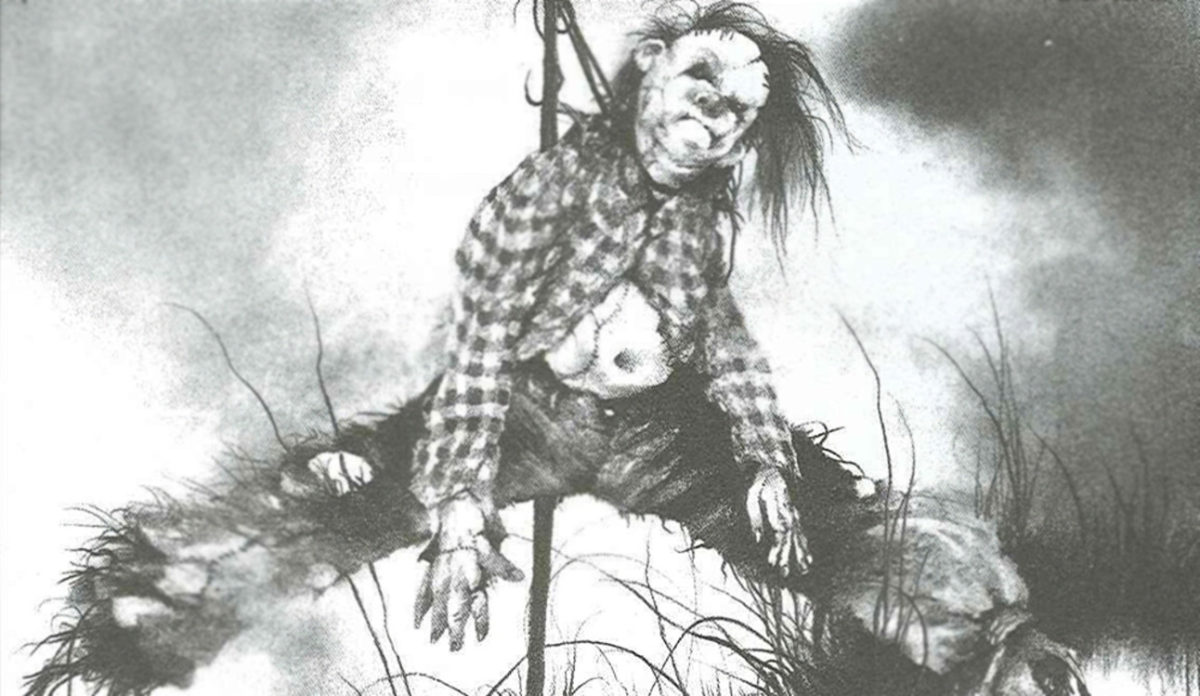

The main illustrator of the entire “Scary Stories” trilogy, Stephen Gammell contributed to arguably the most terrifying aspect of the series: the disturbingly beautiful illustrations and artwork that populate the pages and accompany many of the stories. Done entirely in black-and-white, Gammell presented his images with an eerie messiness that amplified the chaotic nature of the various stories sprawled throughout the books. There’s hardly a moment where we don’t see an image of some sort creep around on the page. It could be something simple like the illustration of a man walking towards a payphone. Unnerving? Yes, but not completely out of the ordinary. Yet, there’s still something off about his figure and face, as well as the uncomfortable use of lighting that blasts its rays over the man.

In other instances, the image was not only considerably larger, but gratuitous to a terrifying degree. We have illustrations that make the readers come face-to-face with an unholy image staring right back at them. The disjointed, frowning, and bloody bag of straw that is Harold is memorable for his cold gaze that complimented the horrific end to his story. We have a frizzy-haired woman in a close-up illustration looking on in horror as that red spot on her face starts to pulsate. We have a pair of bloody feet dangling from the chimney, but to whose body are they attached and why are they in the chimney?

Of course, I can’t talk about Gammell’s messed up imagery without talking about the tale of “The Haunted House” from the first book. The story itself is plenty familiar: a man stays the night at an old house that is haunted by a tragic spirit looking to right a wrong from their life. Pretty cut-and-paste and no reason to remember it, right? Well, not with Stephen Gammell in the mix! This otherwise familiar story is among the most notorious in the entire trilogy and that is all thanks to the trauma-inducing illustration of the spirit’s face in all its melted and eye-less glory. The hair is tattered, the skin is falling off the bone, and did I mention that there are no eyes? Just black holes of nothingness.

I read these stories and saw these pictures in second grade.

The insanity of the “Scary Stories” trilogy being readily available for kids in the Scholastic Book Fair was unreal and it still feels like a strange fever dream to me. I was personally never into horror during that age, focusing my attention on cartoons and slapstick comedy to eat up my time. But something about the covers of the books intrigued me. I had never seen covers quite as morbidly inventive as a clown-like figure popping its head out of the dirt to give me a silly smile. It was almost like an invitation into a book of horrors, one that I decided to take for whatever reason. As soon as I saw the pictures and read the stories, it became clear that I was reading something that might’ve been a bit overwhelming for my 8-year-old brain to process.

Cases like this are primarily why the books were consistently challenged by the American Library Association (ALA). These books were considered children’s literature, yet they featured a multitude of violent scenarios and gruesome illustrations of monsters, oddities, and uncomfortable settings. There is literally a story that ends with a young man being skinned alive and his skin being spread out to dry in the sun. Another story ends with a vengeful spirit eating the liver of a man who unknowingly stood between a rock and a hard place in his house. These stories are R-rated in content, yet casually appear in the children’s sections of literature.

That may seem overbearing for kids, but it’s honestly the perfect function for these stories.

In essence, the “Scary Stories” series embodies the spirit of what folktales are all about. The tales passed down from generation to generation are much older than we think them to be. These are stories that, in some cases, were created hundreds of years ago in response to the fears of the community at that time. Stories like “The White Wolf” and “The Hook” base their horror on real fears of the outside world, such as blood-thirsty animals killing livestock and a killer terrorizing students on campus. The “Sounds” story in the second book, which sees two men staying in a house populated by a mad killer, was in response to a 19th century story of a man living in a large home isolated with his daughter. The stories we read are responses to what we observe.

Storytelling in general functions like this, but the timeless nature of the tales in “Scary Stories” feels very unique in its presentation. Each of the stories are incredibly short in length, with the longest ones only running a couple of pages. But there’s an earnest sincerity to the stories’ simple writing and execution. The heart of the conflict is presented in the most clear-cut way possible, no matter how insane the stories can get. It’s a story you’d expect to hear from one of your friends as you sit around a campfire just shooting the shit with everybody. The supposed local legend of a killer that roams the nearby area or a similar atrocity that haunts the area is the kind of story expected to be found in these books. It’s simple and enjoyable to read the stories as they are presented because they are written in such a casual manner that makes it easier to connect with the story and the person telling said story.

But where Stephen Gammell truly hit the mark was his decision to bring these old tales to life with actual imagery for us to associate the stories to. We’ve heard countless tales of ghosts roaming around empty houses, but Gammell took that concept re-presented by Alvin Schwartz and illustrated a ghastly, deteriorating, and gruesome face for us to forever associate spirits to. Sure, it’s not the only way to interpret a haunted house story, but people who have consumed these books in their childhood may have this image in the back of their head until the end of time. It’s such a deep dive into pure horror for children and that kind of trauma can stay with a person, despite how minor it may be to other forms of trauma.

Gammell’s illustrations were horrific and downright traumatizing to a certain degree, but they never officially crossed a line into pure tastelessness. There is a strange gray area where these images exist, being between over-the-top goofy and disturbingly real. They’re the kind of images that can easily be read as nothing more than fiction, but still have a degree of horror that lives on past the pages. For the longest time, that pale lady from “The Dream” in the third book was my paralysis demon, hovering over me as I struggled to sleep. I know she’s technically fake, but her presence still lived on in my life long after I hastily read that story so I could skip to the next one and never look at her face again.

These are the kinds of stories that we could easily make adjustments to and tell our own friends, family, and acquaintances. That is the very reason they continue to live on in media. Stories of serial killers, urban legends, and other unnatural things in the night continue to draw in people looking to get a thrill of some sort. But unlike the short span of a jumpscare in a horror movie, “Scary Stories” combines simple storytelling with disturbing imagery to create an experience where we are not afforded jumpscares. Instead, we slowly soak in the horror of the images as we connect them to the stories and fables told in the book, most of which ended rather unpleasantly. The horror permeates and the images add a layer of engagement that would’ve not been possible with a regular novel that contained no images.

Yes, many books out there can boast to be significantly more well-written and “intelligent” than Schwartz’s collection of adaptations, but the core focus of the books aren’t to showcase its cunning levels of wordplay and masterful writing. “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” gives away its intentions in the title: to tell potentially scary stories in the dark of night. The simplicity of telling stories with your friends as kids is what caused these books to even exist. They’re stories that are so frightening that they continue to live on with modern twists slowly being added with each passing generation.

Even with the film adaptation of the books coming out this summer, it still stands as an example of these stories being adapted for a younger audience. How these stories are delivered remains to be seen, but Guillermo Del Toro and company are doing their hardest to honor the originals with a different take on the stories for the film medium. When one of the masters of horror chooses to adapt Gammell’s specific designs for its monsters and situations in the film, it’s obvious just how much of a frightening impact they had in the wake of their release in the 1980s.

These stories will continue to evolve in their own ways in the future, but the effectiveness of Schwartz and Gammell’s collaborations is perhaps the scariest thing to come out of these books.

Books

‘Halloween: Illustrated’ Review: Original Novelization of John Carpenter’s Classic Gets an Upgrade

Film novelizations have existed for over 100 years, dating back to the silent era, but they peaked in popularity in the ’70s and ’80s, following the advent of the modern blockbuster but prior to the rise of home video. Despite many beloved properties receiving novelizations upon release, a perceived lack of interest have left a majority of them out of print for decades, with desirable titles attracting three figures on the secondary market.

Once such highly sought-after novelization is that of Halloween by Richard Curtis (under the pen name Curtis Richards), based on the screenplay by John Carpenter and Debra Hill. Originally published in 1979 by Bantam Books, the mass market paperback was reissued in the early ’80s but has been out of print for over 40 years.

But even in book form, you can’t kill the boogeyman. While a simple reprint would have satisfied the fanbase, boutique publisher Printed in Blood has gone above and beyond by turning the Halloween novelization into a coffee table book. Curtis’ unabridged original text is accompanied by nearly 100 new pieces of artwork by Orlando Arocena to create Halloween: Illustrated.

One of the reasons that The Shape is so scary is because he is, as Dr. Loomis eloquently puts it, “purely and simply evil.” Like the film sequels that would follow, the novelization attempts to give reason to the malevolence. More ambiguous than his sister or a cult, Curtis’ prologue ties Michael’s preternatural abilities to an ancient Celtic curse.

Jumping to 1963, the first few chapters delve into Michael’s childhood. Curtis hints at a familial history of evil by introducing a dogmatic grandmother, a concerned mother, and a 6-year-old boy plagued by violent nightmares and voices. The author also provides glimpses at Michael’s trial and his time at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, which not only strengthens Loomis’ motivation for keeping him institutionalized but also provides a more concrete theory on how Michael learned to drive.

Aside from a handful of minor discrepancies, including Laurie stabbing Michael in his manhood, the rest of the book essentially follows the film’s depiction of that fateful Halloween night in 1978 beat for beat. Some of the writing is dated — like a smutty fixation on every female character’s breasts and a casual use of the R-word — but it otherwise possesses a timelessness similar to its film counterpart. The written version benefits from expanded detail and enriched characters.

The addition of Arocena’s stunning illustrations, some of which are integrated into the text, creates a unique reading experience. The artwork has a painterly quality to it but is made digitally using vectors. He faithfully reproduces many of Halloween‘s most memorable moments, down to actor likeness, but his more expressionistic pieces are particularly striking.

The 224-page hardcover tome also includes an introduction by Curtis — who details the challenges of translating a script into a novel and explains the reasoning behind his decisions to occasionally subvert the source material — and a brief afterword from Arocena.

Novelizations allow readers to revisit worlds they love from a different perspective. It’s impossible to divorce Halloween from the film’s iconography — Carpenter’s atmospheric direction and score, Dean Cundey’s anamorphic cinematography, Michael’s expressionless mask, Jamie Lee Curtis’ star-making performance — but Halloween: Illustrated paints a vivid picture in the mind’s eye through Curtis’ writing and Arocena’s artwork.

Halloween: Illustrated is available now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.