Editorials

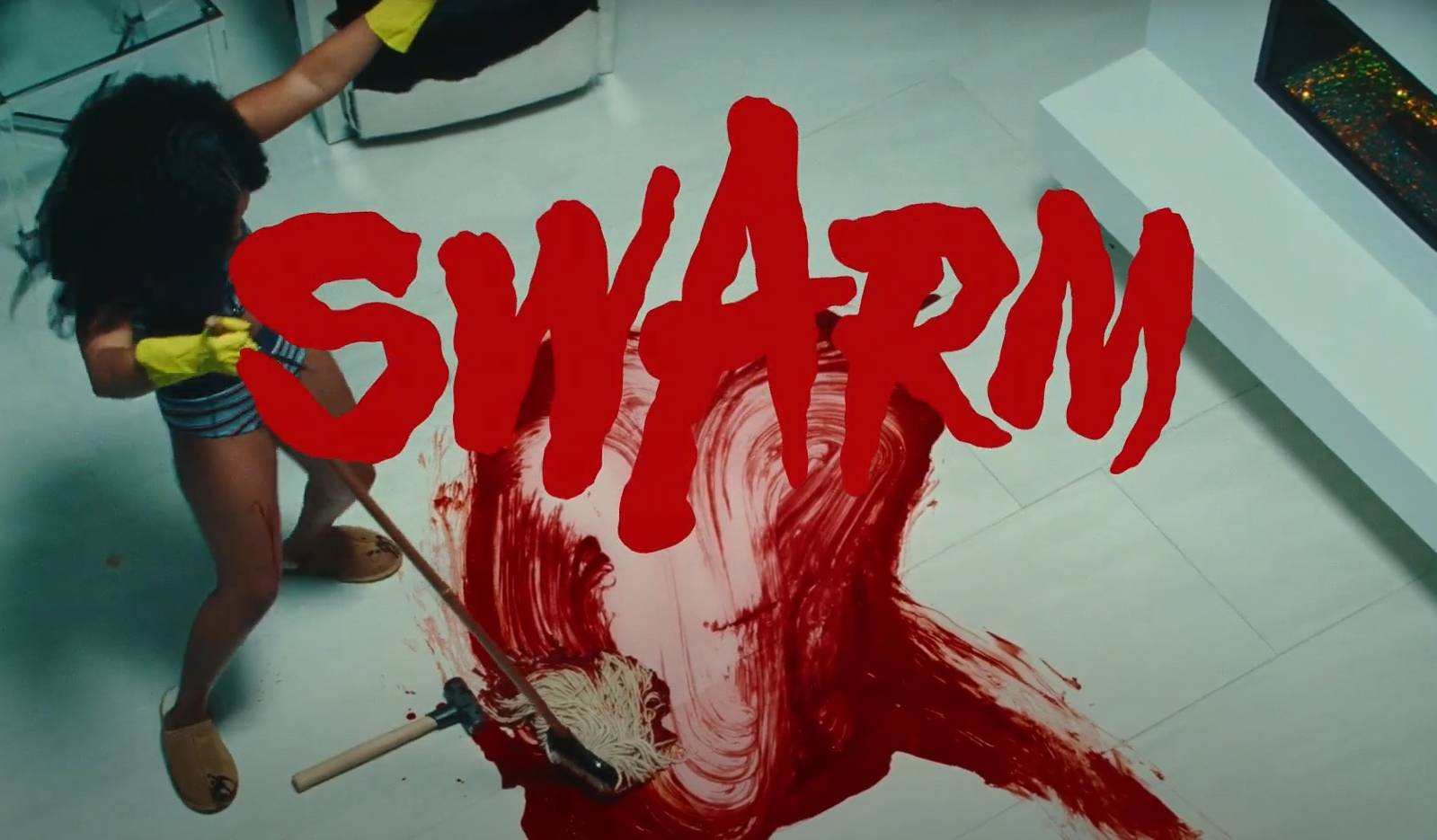

Toxic: “Swarm” and Horror’s Obsession with Obsessed Fandom

“How can fandom be toxic?!” Richie Kirsch (Jack Quaid) scowls after his motive explanation and reveal as one-half of the Ghostface team in last year’s Scream. “It’s about love! You don’t fucking understand– these movies are important to people!”

“Toxic fandom” may only feel like a relatively recent term, used in reference to crazed, niche fandoms of movies, franchises, comics, and musicians alike, especially within online forums and social media groups. However, horror has always known, warned, and held up a mirror to those who take their love of these art forms just a tad bit too far, as depicted in the recent Donald Glover and Janine Nabers-created Amazon Prime show, Swarm.

The quick-to-binge 7-episode series– which subtly nods The Shining, Candyman, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, outwardly supportive but inwardly manipulative cults like Midsommar, and a hypnosis scene straight out of Get Out– follows a young woman named Dre, played by Dominique Fishback, whose performance rivals similar levels of awe as Mia Goth in Pearl (so much so that Twitter has affectionately dubbed the character as the “Black girl version of Pearl”). Dre is obsessed with a fictional version of a Beyoncé-like singer named Ni’jah, to the point in which she looks her victims dead in the eyes and asks “Who’s your favorite artist?” and if they don’t say “Ni’jah,” well, they’re probably done for.

Commenting on Beyoncé’s diehard fandom known in real life as the “BeyHive” and in the show as Ni’jah’s “Swarm” in not-so-subtle ways, each episode begins with the witty disclaimer: “Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is intentional.” It’s so specific in its references to the real singer and the pop culture moments surrounding her that even the first episode takes place in April of 2016, the same month Beyoncé dropped the pivotal visual album Lemonade (and fans at the time just about lost their minds.) Swarm’s Dre goes broke for pricey concert tickets, travels to notable music fests that Ni’jah is headlining, sneaks into VIP after-parties, alienates the few friends or love interests she acquires, and ultimately chooses violence to defend her beloved pop star, after a tragedy in Episode 1 flips her whole world upside down.

But the pitch-black comedy/horror series is more thoughtful and layered than that. The basic elevator pitch of Dre’s mania for Ni’jah may sound outlandish and campy on the surface– and there is a ton of quirky comedy moments, as tonally it’s reminiscent of Glover’s other acclaimed series Atlanta– however, her fandom is deeply rooted in her connection to her sister Marissa, (Chloe Bailey) as the tragic events that surround her sister and the reactions to it from abrasive online communities give Dre a motive to avenge her, as well.

Likely the immediate reaction to that brief synopsis prior to viewing by any horror fan recalls Annie Wilkes in Misery (1990) or the lesser known Simone from Der Fan (1982). Upon her fateful encounter with her beloved Stephen King-like author Paul Sheldon (James Caan), socially isolated, manic, “number one” fan Annie (Kathy Bates) is addicted to the character of Misery, and her disdain for Paul’s choice to kill the character off in his latest novel motivates her to torture and amputate him. In the film adaptation, and even more apparent in the King novel, Annie herself is a metaphor for Paul’s addiction, as she administers pain pills to him as a means of control. While Annie physically punishes Paul, Dre’s goal (initially) seems to be to simply meet her goddess Ni’jah, as she once promised to Marissa…That is, until she, indeed, physically violates Ni’jah.

‘Misery’

In Der Fan, teenage girl Simone (Désirée Nosbusch) is enamored with a new synthwave musician named R (Bodo Steiger) to the point that it becomes her entire personality. When she gets to meet R– and he uses her for sex– R immediately dumps Simone, leading to Simone’s rampage for revenge, with dismembering techniques akin to Audition. Clint Eastwood thriller Play Misty For Me (1971) proceeds the others in this “psycho female fan” trope, as a woman named Evelyn (Jessica Walter) sleeps with a popular radio DJ and becomes unhinged when he pulls away. Annie’s, Simone’s, and Evelyn’s connections to their objects of fixations are all romance-based or psychosexual in different ways, as Paul Sheldon is a romance novelist and Simone and Evelyn are romantically attracted to and ultimately rejected by the men. However, even as Dre’s attraction to women in Swarm becomes apparent over time, her obsession with Ni’jah does not seem to necessarily be attraction-based.

Those interpersonal moments between Annie and Paul (against his will) and Simone and R are almost nonexistent in Swarm, however, in one instance, Dre sneaks her way into a VIP party where Ni’jah is, and the viewer watches on as Dre voraciously bites into a fruit for several seconds, which, in reality, we find out is actually the moment she took a vampire bite out of Ni’jah herself and scurries out of the party. (The bite is a nod to a real-life WTF Beyoncé moment.)

Dre is not only addicted to Ni’jah, Marissa, and killing those who disrespect them– her addiction to ravenously eating food, particularly junk, is similar to watching a feral animal stumble upon a carcass. Post-kill, Dre eats ravenously, often while still covered in blood, including a pie from a victim’s fridge, in one instance. Like the comparable Pearl, the passive, graceless Dre becomes visibly more liberated every time she ends a life.

‘Fade to Black’

In 1981’s The Fan, a deranged man named Douglass (Michael Biehn) stalks Broadway star Sally, (Lauren Bacall) addressing a letter to her: “I am your greatest fan. Because unlike the others, I want nothing from you.” Alas, after Douglass’ attempts at communicating with Sally are thwarted, he goes on to stalking Sally and her loved ones, as the tone within his letters grows increasingly abrasive. In the year prior’s Fade to Black, horror movie maniac and fellow stalker Eric Binford (Dennis Christopher) has his sights set on a modern day Marilyn Monroe lookalike, as she embodies his personal celebrity obsession. Simultaneously, Eric goes on a deranged killing spree, costumed as horror icons and reenacting movie scenes. The Fanatic (2019) sees Moose (John Travolta) idolizing actor Hunter (Devon Sawa) and getting enraged after being cheated out of a chance to meet him.

As mentioned earlier, much of the motivation behind several of the Scream franchise killers (including Billy, Stu, Mickey, Charlie, Richie, Amber) is built upon their unhealthy relationships to movies and franchises, and/or feeling the need to “improve” future Stab movies, as if they know better than the creators themselves. While each of these films within the toxic fan subgenre is a deconstruction of the delusional misfit characters that rely so heavily on their parasocial relationships with pop stars, movies, novelists, and the like– and their entitlement and denial of accessibility to these things– the majority of these particular ones above are even more about incel culture and disenfranchised white male rejection.

…Which is what makes Swarm so unique. Featuring the rare Black female antagonist and the even rarer instance in which that Black female antagonist is a serial killer, whose point of view the audience is following, Dre is perhaps the first of her kind in the genre– with the only exception being Ma (2019) whose titular character doesn’t share the same motivation and is written nowhere nearly as complexly as Dre. Other titles like Le Viol du Vampire (1968), Def by Temptation (1990), Spirit Lost (1996), and When the Bough Breaks (2016) may feature Black women as villains, but their motivations are typically romance/seduction-related or simply vampire queen sovereignty (du Vampire).

Spoiler warning for the ending of Amazon’s ‘Swarm’ (skip this next paragraph if you haven’t seen it)…

Blurring the lines between reality and delusion that culminates by the finale, aptly titled “Only God Makes Happy Endings,” we see through Dre’s unreliable POV, as the viewer realizes what they’re watching is Dre’s fantasy, and what is actually happening to her is bleak. Dre finally makes her way to a Ni’jah concert, after adding to her body count for a ticket. When she moves through the audience and approaches the stage to get closer to Ni’jah, Ni’jah’s face is intentionally blurry. As security tries to remove Dre, Ni’jah’s face is finally revealed to the viewer, but it’s Marissa’s face morphed onto Ni’jah’s body, as Ni’jah tells security to leave Dre be. Ni’jah then whisks Dre out to the backseat of her private car with her, while fans and paparazzi watch them pass. Ni’jah proceeds to gently hold Dre close to her, comforting her in a loving manner, as Dre weeps in her arms. The probable interpretation of this fantasy sequence is that Dre got arrested for, not only invading the stage, but her crimes and murders committed during this spree, and she’s actually being whisked away to the back of a cop car, completely alone. The Marissa/Ni’jah facial hybrid is created to show Dre’s association to the two of them as one, as these two women are the only source of (what she thinks) is real love and connection within her life.

The line between fan and creator is more blurred today than it’s ever been– especially before the eras in which many of the previously mentioned films were made– as creators have become more accessible via social media. With a simple tagging of a Twitter handle or a DM, fans can communicate to creators more easily than ever, and therefore have become more invasive to the boundaries of not only the creators themselves, but also within their interactions with fellow fans. For years, Dre runs a “Swarm” Twitter account with hundreds of thousands of fellow Ni’jah fans (and some haters), which is often her means of selecting her victims and hunting them down. While Dre works solitarily, a mob mentality can often arise within fan communities, as seen in the fan demand for Zack Snyder’s cut of Justice League or fan petitions to “redo” Halloween Ends.

As passionate as any other fandom, (perhaps even more so than others) horror fandom has especially become a place for safeguarding, as the number of horror conventions seems to have grown massively more popular by the year, and the genre has become more viable and marketable to the mainstream. Not dissimilar to Dre, horror fans are protective of their genre, their franchises, their filmmakers, their final girls, their villains, and those that portray them (Toni Collette’s Oscar snub for Hereditary is still a sore spot for the horror community). Horror is the best way to tell these stories, as it’s fully aware of how quickly our passion can become lunacy and acts as a fable for what can happen when we take our love of it too seriously.

Horror fans are hopefully better at managing our issues via catharsis through the movies and not the creators themselves, but if Swarm and these movies have taught us anything, we could all do a better job at checking our fandoms– before we whip out the weapons and say “Who’s your favorite___?”

“Swarm”

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.