Editorials

Artificial Invasion: Why the World Is Ready for a New ‘Body Snatchers’ Movie

Every generation gets the Invasion of the Body Snatchers movie it deserves. To date, there have been four official adaptations of Jack Finney’s 1954 novel The Body Snatchers and each one adapts its premise to the concerns of the time in which it was made. The deep core of the novel asks, “what exactly is it that makes us human?” and then examines it through a non-human threat that attempts to replicate humanity but just can’t get it quite right. Every twenty years or so, a new version of the story applies that question to the current climate. We are right around that twenty-year mark. We are ready for a new Body Snatchers movie, and it should be about Artificial Intelligence.

In 1954 and 1956 when the novel and the first film version of the story directed by Don Siegel were released, the Cold War was America’s preoccupation. The brilliance of that original film is that it can be read from either side of the political divide. Anti-communists could see the Pod People as the Soviet hordes trying to take over American individualism. The anti-McCarthy crowd could say that the actions of the Anti-communist witch hunts led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, Richard Nixon and others were destroying the American soul built on the ideals of freedom of speech, expression, and association. Don Siegel claimed that neither was true, that it was just a good story. This only proves the effectiveness and malleability of Invasion of the Body Snatchers for decades to come.

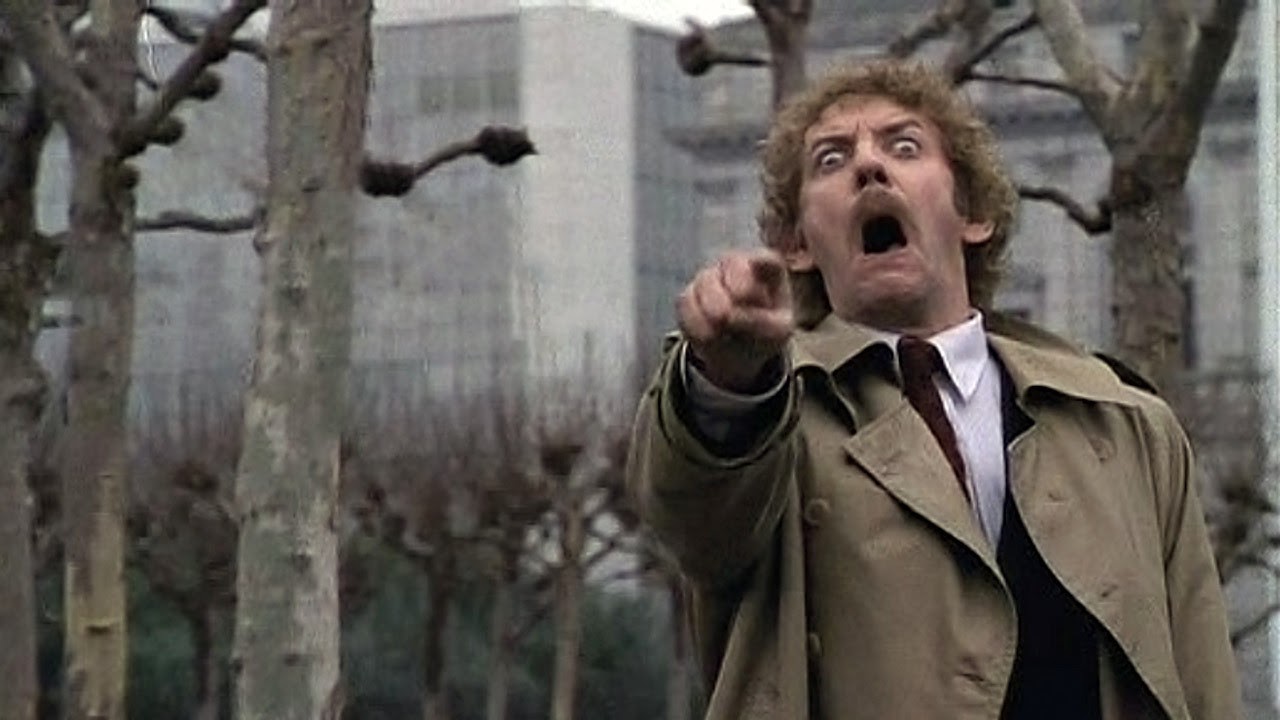

The 1978 adaptation, directed by Philip Kaufman is still arguably the best of the bunch (though many give unwavering allegiance to the original). The 1970s were a time of searching for meaning in the wake of Watergate, the collapse of the hippie and anti-war movements, and more. Self-help and religious cults abounded in the wake of the perceived “failure of the 60s” with pseudo-psychological gurus filling the vacuum of man’s search for meaning. Of all the adaptations of the story, this retains the most relevance today in our time of political divisions, social alienation, social media induced echo chambers, and conspiracy theories.

Abel Ferrara’s 1993 film Body Snatchers is the most overtly political adaptation and a response to the culmination of a decade of military buildup, most of it during peacetime. With decades of Cold War ending in the collapse of the Soviet Union, the film asks why the US was still devoted to its massive military might. Was it really “peace through strength” or positioning the United States to be a worldwide police force and more importantly, what effect does this have on the psychology and personality of the nation. In essence, are we as a nation losing our souls in this buildup and becoming a culture of conformity in the process?

‘Body Snatchers’ (1993)

In the smallest interval between official adaptations, a great deal happened, specifically in the science of genetics. In 1996, Dolly the sheep was cloned, the Human Genome Project was completed in 2004, and stem cell research became a hot-button political issue. Concerns were raised about the genetic alteration of foods and the effect it would have on human biology and psychology. Of all the versions of The Body Snatchers, The Invasion (2007) is considered the least effective despite the involvement of superstar producer Joel Silver and a cast led by Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig. It does, however, tap into the contemporary fears of the era and ask the important questions asked by every version of the story.

The questions at the heart of every adaptation are clear: is there something beyond biology, intellect, memories, and experiences that makes us human? and would giving ourselves over to certain trends and conveniences rob us of that humanity? Thousands of years of philosophy, religion, and science haven’t been able to make a definitive declaration one way or the other, so I certainly cannot make an airtight argument for the existence of a soul. I can however suggest that we recognize the presence of human agency when we see it, or more to the point, when we don’t. In Jack Finney’s original novel, Wilma, a young woman, describes to the lead character, Dr. Miles Bennell, why she believes that her Uncle Ira is no longer really her Uncle Ira:

“‘Miles, he looks, sounds, acts and remembers exactly like Ira. On the outside. But inside he’s different. His responses”—she stopped, hunting for the word—’aren’t emotionally right, if I can explain that. […]there was—always—a special look in his eyes[…]Miles, that look, ‘way in back of the eyes, is gone. With this—this Uncle Ira, or whoever or whatever he is, I have the feeling, the absolutely certain knowledge, Miles, that he’s talking by rote. That the facts of Uncle Ira’s memories are all in his mind in every last detail, ready to recall. But the emotions are not. There is no emotion—none—only the pretense of it. The words, the gestures, the tones of voice, everything else—but not the feeling.’”

In the 1978 adaptation, the invaders can be fooled by not showing emotion, but the humans know that something is off, that their loved ones have been taken over. Humanity sees and responds to humanity, and that cannot be synthesized. There is an intangible beyond the sum of intellect and experience that makes us who we are. So, call it whatever you want—a soul, mojo, life force, je ne sais quoi, the X factor, or “it,” there is something that cannot entirely be explained that makes humans human, that a machine simply does not have and will never have. And this is why we are not only due for a new Body Snatchers film, but it absolutely must be about Artificial Intelligence.

There are many wonderful uses for A.I. It is an extraordinarily helpful scientific tool, for example. It can extrapolate weather patterns, chart climate change, predict the spread of viruses, and so on, giving humans a template to help foresee and intervene in various crises. It has been a great asset in medical research and the production of vaccines and life-saving medicines. A.I. is wonderful for things that require cold precision or predictive models. In movies, it can help make computer-generated crowd scenes, for example, more authentic. I have no problem with the use of A.I. in certain circumstances. I’m not too worried (yet) that we are in the process of creating a Skynet, Matrix, or Battlestar Galactica situation. What I object to is the placement of artificial intelligence at the center of the creative process.

‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ (1956)

Creativity is a uniquely human pursuit. We create to seek meaning, to hold the mirror up to nature, to discover who we are. A.I. doesn’t care about any of those things. By handing the creative process over to A.I. merely to save time and money we are quite literally selling our souls. The spark of creativity is driven by the engine of humanity. It is this spark that the invaders in the Body Snatchers stories cannot replicate, and neither can A.I. It can be told the parameters and process the probable outcomes, but it cannot understand what it means to be human. It is incapable of offering a surprising and illogical human solution to a plot point that causes us to sit forward in our chair or take a sharp intake of breath when we see something we have never seen before.

It does not know how deeply heartbreak hurts, it doesn’t feel the sting of disappointment, the joy of connection, the ecstasy of making love or seeing a sunset. It does not feel the longing for something better or have any hope for the future. It can analyze the works of Mozart or Beethoven and create the missing pieces of the Requiem or write a “Tenth Symphony” (Beethoven wrote nine, but died in the early stages of another), but they can never be the works of genius that the men themselves would have written had they lived. All A.I. can do is produce derivation based on existing information. All it can do is produce mediocrity. A hollow imitation. It can rehash and repackage but it cannot truly innovate. It cannot transcend or surprise. Our humanity cannot be touched in that special way that only great art can by something that has no humanity. It reduces the act of creativity to a parlor game.

In the film Amadeus, Mozart is called upon to play a familiar tune in the style of J.S. Bach, which he proceeds to do quite well. Is it how Bach would have arranged the melody? Almost certainly not, but in that case at least it is filtered through a creative entity who not only has similar knowledge, but similar feelings. If the same trick were performed by A.I. it would be technically correct but joyless, hollow, lacking any kind of soul. We may not be able to pinpoint exactly why, but something about it would strike us as “wrong” or “off.” The humanity in us recognizes the humanity in others and by extension the humanity in art. When A.I. is used as a parlor trick, it can be a diverting pastime, but when it is seriously being considered to produce art, it is dangerous.

Some may argue that current filmmakers can only assimilate what has come before and repackage it. This is a regular criticism aimed at filmmakers like George Lucas, Brian DePalma, and Quentin Tarantino. What critics of these and others fail to recognize is the innovation with which they amalgamate what has come before, through the filter of their unique humanity and creativity, into something new and exciting. Yes, George Lucas was inspired by space and adventure serials of the 30s when he created Star Wars and Indiana Jones, but the result is neither Flash Gordon nor Allan Quatermain. De Palma was a student of Hitchcock, but his best films advance the tools of the Master of Suspense to a new level. Tarantino tosses the ingredients of exploitation, 70s action cinema, and king fu movies into a stew that becomes something unique and often greater than the sum of its parts. Their visions are unique and rise far above facsimile.

Imagine downloading all of Quentin Tarantino’s knowledge and personal experience along with the scripts he has written into a computer equipped with A.I. It still would not be able to produce the script for a hypothetical eleventh Tarantino movie. Even if it knows everything that Quentin Tarantino knows it lacks one important element—it is not Quentin Tarantino. In other words, only he could make Pulp Fiction or Kill Bill or Once Upon a Time…In Hollywood because his films are more than the sum of their parts just as humans are somehow more than the sum of theirs.

‘The Invasion’ (2007)

In the world of the Pod People, the only pursuit of life is survival, but it seems like there is not much reason to survive. There is no artistic expression or creativity of any kind, only the collective work that needs to be done for continued existence. It is a world of conformity and detachment. In the 1978 version, the Pod Person Dr. David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy) states that they came from a dead planet implying that once they have depleted earth’s resources, they will ride the solar winds to another planet, then invade and deplete it as well. The Pod People only know how to exist and consume, they do not know how to live.

Art is meant to not merely pass the time, but feed our souls, and one thing we need as humans is nourished souls. We need our imaginations to be set free, our creativity unbound—relying on A.I. to fill this role will only chain them. A common complaint about Hollywood is that it is all out of ideas. Everything is remakes, sequels, and I.P., there is nothing new under the sun. Giving filmmaking over to Artificial Intelligence will only make this worse, butchering and puréeing even what we have now into a bland, tasteless soup of mediocrity. Right now, the WGA and SAG-AFTRA workers on the picket lines seem to be the only thing standing between us and this nightmare scenario becoming a reality—fight on friends!

But then maybe it’s too late for this argument. A.I. is already here, there’s no stopping it, and you’re next…

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.