Editorials

‘Tom at the Farm’ Grapples with Masculinity and Québec History [Maple Syrup Massacre]

Maple Syrup Massacre is an editorial series where Joe Lipsett dissects the themes, conventions and contributions of new and classic Canadian horror films. Spoilers follow…

There’s a moment, very late in Tom at the Farm, when the film’s antagonist Francis Longchamp (Pierre-Yves Cardinal) wears a denim jacket with USA emblazoned on the back. The film’s protagonist – Tom (Xavier Dolan, also the co-writer and director) – has been held hostage by Francis for several weeks by this point while the pair role play domestic roles in a psychosexual power game. Francis, it should be noted, is also the older brother of Tom’s recently deceased lover and Tom submits to the ruse, in part, because Francis smells and resembles his ex.

At the end of the film, however, Tom finally flees into the Québec woods, steals Francis’ car, and escapes back to the safety of Montreal, the largest city in the province and the third biggest in Canada.

There are several Canadian elements embedded within the aforementioned plot synopsis of Dolan’s adaptation of Michel Marc Bouchard’s play of the same name. Tom at the Farm leans into the urban vs rural divide (last discussed in Rituals) and the film employs the same Canadian male archetypes outlined by Robert Fothergill in Backcountry, the very first entry of this editorial series. There’s also a conversation to be had about the “French-ness” of the film, which is often depicted and/or treated as its own nation in Canadian cinema (see the entry on Rabid for a partial historical primer).

Tom at the Farm begins with a post-credit aerial sequence as Tom drives through the Québecois countryside. Bill Marshall’s article “Spaces and Times of Québec in Two Films by Xavier Dolan” immediately identifies the “rectilinear road through fields and farms” as Richelieu (the film was shot around Saint-Blaise, QB), evident by “the division into rangs…that characterized New France’s cadastral system, the twentieth-century network of paved roads for motor traffic.”

In his article, Marshall explores how the film fits into not only “representations in Québec fiction of the countryside… but also of the (re)transplantation of the urban subject/protagonist into a rural setting.” In this sense, Tom is a fish out of water: a big city advertising executive who finds himself out of his depth when he becomes embroiled in the lives of his dead lover’s mother Agathe (Lise Roy) and her surviving adult son, who still lives with her and works the family farm.

Fulvia Massimi’s piece “A Boy’s Best Friend is His Mother: Québec’s Matriarchy and Queer Nationalism in the Cinema of Xavier Dolan” believes that “Dolan’s fascination for [the play] is understandable, since it provides the ground for a close examination of disturbed familial dynamics as well as the key to accessing Québec’s nationalist discourse through a different stylistic approach.” Dolan has made a career, at least early on, of exploring the emotionally fraught relationships between mothers and sons (see: I Killed My Mother, Mommy, Heartbeats, etc).

Massimi’s analysis centers less around Tom than Francis, who she believes is representative of the identity politics that arose in the wake of the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. That Francophone Nationalism project, lead by politician Jean Lesage, involved “a series of drastic political, societal and cultural changes” (The Canadian Encyclopedia) as the province moved away from the Catholic church and towards modernization and secularization. This involved taking control of the schools, training future francophone leaders for politics, and the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism which confirmed English and French as the bilingual official languages of Canada.

The Quiet Revolution was heavy with gendered and homophobic connotations. As Massimi explains, the 60s movement was equated with “the promotion of male heterosexual power as a way to overcome the myth of Québec’s “homosexual” nation—since [it had been] historically emasculated by the Church and subjugated by the Anglophone colonizer.” From this perspective, a new Québec needed to get out from under the oppression of the Church and the English (speaking politicians and citizens) in order to become its own entity.

By comparison, “Bouchard [the playwright]’s more contemporary work offers a significant account of Québec’s national scenario by challenging familial roles and gendered subjectivities in a way that resonates the intent of Dolan’s cinema as well.” This is evident principally in the character of Francis, whose homophobic and misogynistic behaviour is also a disguise for the homosexual relationship he forces on with Tom (and also speaks to his implied incestuous relationship with Tom’s dead lover and Francis’ brother, Guy).

The film is filled with beautiful, evocative and uncomfortable imagery, particularly the way that Francis physically controls Tom to ensure he cannot leave the farm. Not only does Francis strand Tom by removing the tires from his car, he terrorizes and physically assaults Tom. The fascinating component is Tom’s Stockholm Syndrome infatuation with Francis: the interplay between sexual attraction and violence is repeatedly evident in situations such as when Francis wakes Tom up in bed, forces Tom into a bathroom stall, walks in on Tom in the shower, and leads Tom in a tango in the barn (Tom is, of course, dancing “the female” role).

Massimi sees the character as a proxy for Québec masculinity in the wake of the Quiet Revolution: “The homophobic, hyper-sexualized character of Francis epitomizes the dysfunctional male subject, who is produced…by the unsuccessful design of the Quiet Revolution…his sexual ambiguity and his submission to his controlling mother disclose[s] the failure of Québec’s nationalism to brand itself as a masculine project.” Sidebar: this is also in keeping with Fothergill’s characterization of the bully.

Which brings us back to the end of the film. Ballard notes that Dolan’s film features references and homages to US genre texts, including The Shining (the opening aerial) and several Hitchcock texts (the shower scene is Psycho and the corn chase is North by Northwest).

The USA denim jacket that Francis wears, then, is part of the film’s larger conversation about power and authority by a threatening “older brother” figure. Francis is representative of both the failure of the “masculine project” of the post-Quiet Revolution male in Québec, as well the province’s relationship to the larger Anglophone population in Canada, as well as Canada’s relationship to our neighbours to the South.

Sometimes the relationship is kind, romantic and reciprocal; others times it is regressive, repressed, and dangerous.

If the wardrobe isn’t enough, “Dolan chooses to end his film with Rufus Wainwright’s 2007 ‘Going to a Town’ (‘I’m going to a town that has already been burnt down/I’m so tired of you, America/Making my own way home, ain’t gonna be alone/I’ve got a life to lead, America’), a song very explicitly about Dolan’s fellow-gay-but-anglophone-Montrealer’s disillusionment with the United States and the Bush years” (Marshall).

The circularity of Tom at the Farm suggests that there’s no easy way to break free of an abusive relationship. After the funeral when Francis first beats him, Tom makes a futile attempt to drive off, but winds up circling back and returning to the farm. The film’s ambiguous ending also suggests that, despite finally returning to the safety of Montreal after weeks being held captive, Tom contemplates going back to Francis.*

*It should be noted that this is substantially different from the play, where Tom murders Francis and (it is implied that he) assumes the role of Agathe’s surrogate son.

Much like the politics of real life, there truly is no escaping the past.

Editorials

The Lovecraftian Behemoth in ‘Underwater’ Remains One of the Coolest Modern Monster Reveals

One of the most important elements of delivering a memorable movie monster is the reveal. It’s a pivotal moment that finally sees the threat reveal itself in full to its prey, often heralding the final climactic confrontation, which can make or break a movie monster. It’s not just the creature effects and craftmanship laid bare; a monster’s reveal means the horror is no longer up to the viewer’s imagination.

When to reveal the monstrous threat is just as important as HOW, and few contemporary creature features have delivered a monster reveal as surprising or as cool as 2020’s Underwater.

The Setup

Director William Eubank’s aquatic creature feature, written by Brian Duffield (No One Will Save You) and Adam Cozad (The Legend of Tarzan), is set around a deep water research and drilling facility, Kepler 822, at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, sometime in the future. Almost straight away, a seemingly strong earthquake devastates the facility, creating lethal destruction and catastrophic system failures that force a handful of survivors to trek across the sea floor to reach safety. But their harrowing survival odds get compounded when the group realizes they’re under siege by a mysterious aquatic threat.

The group is comprised of mechanical engineer Norah Price (Kristen Stewart), Captain Lucien (Vincent Cassel), biologist Emily (Jessica Henwick), Emily’s engineer boyfriend Liam (John Gallagher Jr.), and crewmates Paul (T.J. Miller) and Rodrigo (Mamadou Athie).

Eubank toggles between survival horror and creature feature, with the survivors constantly facing new harrowing obstacles in their urgent bid to find an escape pod to the surface. The slow, arduous one-mile trek between Kepler 822 and Roebuck 641 comes with oxygen worries, extreme water pressure that crushes in an instant, and the startling discovery of a new aquatic humanoid species- one that happens to like feasting on human corpses. Considering the imploding research station, the Mariana Trench just opened a human buffet.

The Monster Reveal

For two-thirds of Underwater’s runtime, Eubank delivers a nonstop ticking time bomb of extreme survival horror as everything attempts to prevent the survivors from reaching their destination. That includes the increasingly pesky monster problem. Eubank shows these creatures piecemeal, borrowing a page from Alien by giving glimpses of its smaller form first, then quick flashes of its mature state in the pitch-black darkness of the deep ocean.

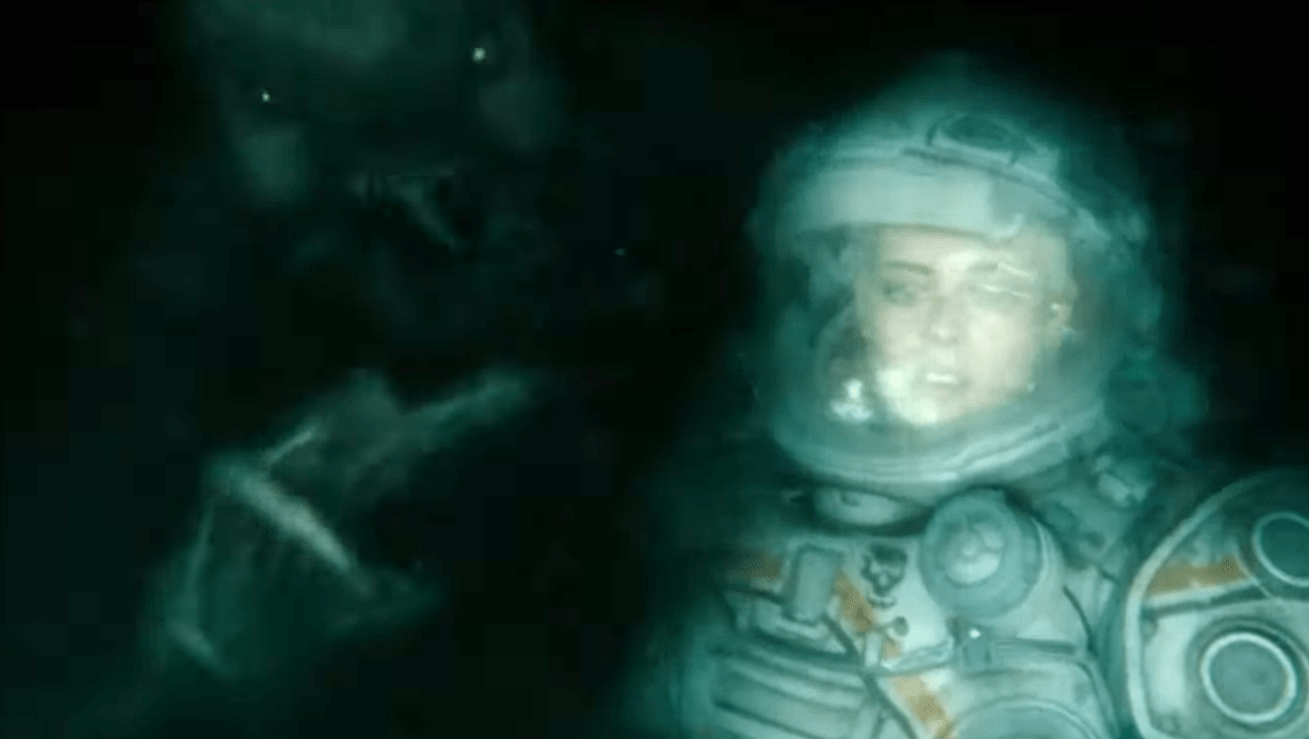

The third act arrives just as Norah reaches the Roebuck, but not before she must trudge through a dense tunnel of sleeping humanoids. Eubank treats this like a full monster reveal, with Stewart’s Norah facing an intense gauntlet of hungry creatures. She’s even partially swallowed and forced to channel her inner Ellen Ripley to make it through and inside to safety.

Yet, it’s not the true monster reveal here. It’s only once the potential for safety is finally in sight that Eubank pulls the curtain back to reveal the cause behind the entire nightmare: the winged Behemoth, Cthulhu. Suddenly, the tunnel of humanoid creatures moves away, revealing itself to be an appendage for a gargantuan creature. Norah sends a flare into the distance, briefly lighting the tentacled face of an ancient entity.

It’s not just the overwhelming vision of this massive, Lovecraftian entity that makes its reveal so memorable, but the retroactive story implications it creates. Cthulhu’s emerging presence, awakened by the relentless drilling at the deepest depths of the ocean, was behind the initial destruction that destroyed Kepler 822. More importantly, Eubank confirmed that the Behemoth is indeed Cthulhu, which means that the humanoid creatures stalking the survivors are Deep Ones. What makes this even more fascinating is that the choice to give the Big Bad Behemoth a Lovecraftian identity wasn’t part of the script. Eubank revealed in an older interview with Bloody Disgusting how the creature quietly evolved into Cthulhu.

The Death Toll

Just how deadly is Cthulhu? Well, that depends. Most of the on-screen deaths in Underwater are environmental, with implosions and water pressure taking out most of the characters we meet. The Deep Ones are first discovered munching on the corpse of an unidentified crew member, and soon after, kill and eat Paul in a gruesome fashion. Lucien gets dragged out into the open depths by a Deep One in a group attack but sacrifices himself via his pressurized suit to save his team from getting devoured.

The on-screen kill count at the hands of this movie monster and its minions is pretty minimal, but the news article clippings shown over the end credits do hint toward the larger impact. Two large deepsea stations were eviscerated by the emergence of Cthulhu, causing an undisclosed countless number of deaths right at the start of the film.

Norah gives her life to stop Cthulhu and save her remaining crewmates, but the Great Old One isn’t so easily vanquished. While the Behemoth may not have slaughtered many on screen here, his off-screen kill count through sheer destruction is likely impressive.

But the takeaway here is that Underwater ends in such a way that the Lovecraftian deity may only be at the start of a new reign of terror now that he’s awake.

The Impact

Neither Underwater or Cthulhu overstay their welcome here. Eubank shows just enough of his Behemoth to leave a lasting impression, without showing too much to ruin the mystery. The nonstop sense of urgency and survival complications only further the fast-paced thrills.

The result is a movie monster we’d love to see more from, and for horror fans, there’s no greater compliment than that.

Where to Watch

Underwater is currently available to stream on Tubi and FX Now.

It’s also available on Blu-ray, DVD, and Digital.

In television, “Monster of the Week” refers to the one-off monster antagonists featured in a single episode of a genre series. The popular trope was originally coined by the writers of 1963’s The Outer Limits and is commonly employed in The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and so much more. Pitting a series’ protagonists against featured creatures offered endless creative potential, even if it didn’t move the serialized storytelling forward in huge ways. Considering the vast sea of inventive monsters, ghouls, and creatures in horror film and TV, we’re borrowing the term to spotlight horror’s best on a weekly basis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.