Editorials

‘The Blair Witch Project’ at 25: The Eerie Real Life Parallels to the Legend of the Blair Witch

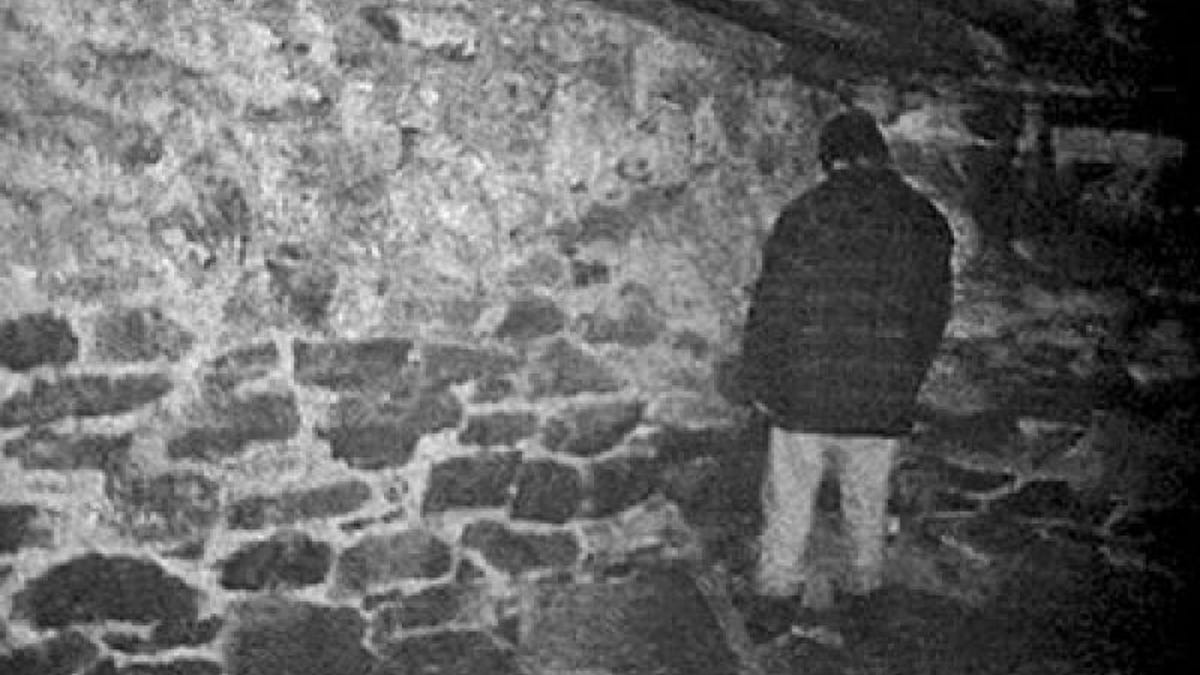

Few films have changed the landscape of horror like The Blair Witch Project. Purporting to be recovered footage from a doomed documentary, the story follows three filmmakers who venture into the Black Hills of Maryland to investigate the legend of the Blair Witch. They never return. This lean and mean film was cobbled together from hours of footage shot by the actors improvising fictionalized versions of themselves. Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez made the bold choice to never show the titular monster, elevating the film from a creepy tale set in a haunted woods to one of the most terrifying, profitable, and ambitious horror films of all time. Though her face remains in the shadows, the Blair Witch has become a cultural phenomenon with a legacy that reaches far beyond the real life entities who may have inspired her creation.

Because Heather (Heather Donahue), Josh (Joshua Leonard) and Mike (Michael C. Williams) were never able to finish their documentary, we don’t learn much about the Blair Witch from the original film. “Man on the street” interviews and passages from an old book provide just a taste of this terrifying tale. As part of an ingenious marketing campaign, Myrick and Sánchez worked with Ben Rock to create extensive lore for Curse of the Blair Witch, a mockumentary that premiered on The Sci-Fi Channel in conjunction with the film’s theatrical release.

After learning more about the missing filmmakers, a collection of faux experts tell us the story of Elly Kedward, an 18th century woman living in the township of Blair. Likely due to religious differences and reports that she’d been bleeding local children, Elly was convicted of witchcraft and subsequently banished from the town. Unfortunately this sentence may have been a way to subvert a formal execution. Blindfolded, Elly was driven deep into the wintery woods, tied to a tree, and left to die…

Moll Dyer and Elly Kedward’s Legacy of Blood

Elly’s fictional demise was likely inspired by the legend of Moll Dyer, a witch said to haunt the woods of Leonardtown, Maryland. Though experts remain unsure of her actual existence, Moll Dyer was a 17th century colonist and outcast in the struggling community. During a particularly harsh winter following a poor harvest, the frightened villagers embraced superstition and blamed Moll for their misfortune. Accounts of the story vary with some versions describing angry neighbors setting fire to Moll’s home while others insist she merely heard the mob approaching and fled moments before their arrival. Both variations remember Moll dashing through the snowy woods with only a light shawl to keep her warm. When her strength eventually gave out, Moll is said to have placed her right hand on a rock and extended her left to the sky in order to call down a curse on the people of Leonardtown. She was later found frozen in this position and the rock still bears the imprint of her mystical contact. It has since been relocated and now sits in front of the Leonardtown courthouse as a grim reminder of this legendary injustice.

A year after Elly’s similar murder, the children of Blair began to disappear one by one. Fearing her revenge from beyond the grave, they fled the area and the village eventually died out. When the town of Burkittsville was established on the land decades later, rumors began to swirl of a sinister presence haunting the nearby woods. Locals swore they had seen a woman hovering above the forest floor with command over the animals and trees. When a little girl named Eileen Treacle drowned in a nearby creek, witnesses claimed to see a ghostly hand emerge from the water to pull her under. Spotting mysterious stick figures littering the stream, the villagers began avoiding the creek and feared that contact with the water might spread the witch’s curse.

But the bloodiest chapter of the witch’s story was yet to come. In 1886, a little girl named Robin Weaver disappeared after playing in the woods. She later reappeared on her grandmother’s porch and claimed that a lady whose feet never touched the ground had led her to a house deep in the woods. The search party sent to retrieve her had not yet returned so additional men were dispatched to call off the hunt. Unfortunately they found only death. The second search party stumbled upon the five men stretched out on what would come to be known as Coffin Rock. Each man tied to the next, they had been disemboweled with pagan symbols carved into their skin. Hours later, the bodies had vanished but the smell of carnage remained heavy in the air.

The Curious Case of the Bell Witch

Before diving into Blair Witch lore, a historian featured in Curse of the Blair Witch mentions a similar case in Adams, Tennessee. The Bell Witch is a well-documented paranormal entity that haunted the Bell family of Red River in the early 17th century. Family patriarch John Bell first noticed a large dog with the head of a rabbit lingering on the family’s land followed by curious sightings of a strange girl wearing a green dress. The witch’s torment began as harmless pranks: knocking on the walls at night and pulling covers off of the sleeping family. This soon escalated to physical attacks as the Bells were slapped, scratched, pinched, and stuck with pins. Most of the cruelty was focused on John, who suffered paralysis of the mouth, and daughter Betsy who would frequently collapse under the stress of this violence.

As the hauntings escalated, the Bell Witch developed an audible voice she would use to taunt the family. When asked about her origins, the voice claimed “I am a spirit; I was once very happy but have been disturbed.” The witch quickly became a constant presence on the farm and word of what the Bells would call “the family trouble” spread throughout the southeast region. Visitors traveled from far and wide to hear the witch including multiple failed attempts to debunk the haunting. Though her torment of John and Betsy never wavered, the witch enjoyed entertaining and was known to perform parlor tricks for visiting guests. She would routinely share gossip from neighboring households and, after appearing to leave for short periods of time, would recite passages from different sermons given miles away. The strange tale was featured in an edition of the Saturday Evening Post and future president Andrew Jackson was among the high profile visitors to the Bell farm.

While the entity gave several explanations for its origin, many believed it emerged from a burial ground disturbed when the Bells built their home on the land. The spirit also claimed to be “Old Kate Batts’ witch,” referring to an older woman from town. Kate was a large and aggressive woman with a habit of begging pins from her neighbors. Before the hauntings began, John had a public dispute with this boisterous widow giving rise to the theory that the hauntings were her clandestine attempts at revenge. Miraculously, Kate was never formally charged with witchcraft and lived her life in relative peace. In his accounting of the tale, Betsy’s own brother noted Kate’s kindness and overall decency, fully rejecting the idea that she had brought this curse down upon the family.

Death and Documentation

One of the few completed scenes in the unfinished Blair Witch documentary features Heather reading the gruesome story of Coffin Rock from an old book. Published in 1809, The Blair Witch Cult is a collection of first-hand accounts of Blair Witch encounters and strange occurrences in the Black Hills she’s known to haunt. Though this primary source was created by the filmmakers as an eerie prop, it was likely inspired by a real publication. Authenticated History of the Bell Witch is a similar collection of interviews and stories from those who witnessed the Bell family hauntings. Chapters of this exhaustive account include an exploration of the Adams community, details of religious fervor, and well-documented conversations with friends, neighbors, and members of the Bell family. Published in 1894 by respected editor Martin V. Ingram, this primary source with its notable red cover is believed to be the first complete chronicle of this mysterious phenomenon.

When recounting little Eileen’s death in the Burkittsville river, experts featured in the faux documentary note that this tragic occurrence marks the first time in recorded history that a death was attributed to a non-human entity. However, this notorious distinction actually belongs to the Bell Witch. After suffering direct threats and unseen harassment for years, John Bell fell inexplicably ill. Doctors were unable to find the cause of his malady, but recovered a small vial filled with a deadly liquid. He eventually succumbed to the poison, delighting the witch who celebrated his passing with crude jokes and drinking songs.

Modern Variations

The witch’s disturbances eventually tapered off, disappearing altogether once Betsy called off her engagement to her neighbor Joshua Gardner. Though many explanations have been given over the years, including ventriloquism and poltergeist activity, no one has ever been able to prove what actually happened in the Bell home. In 1997, horror author Brent Monahan published a fictionalized account of the story in The Bell Witch: An American Haunting with a surprising explanation for the occurrence. Told through the lens of Betsy’s eventual husband, Richard Powell, Monahan posits that the hauntings were a manifestation of Betsy’s attempts to protect herself from abuse at the hands of her father.

Experts in Curse of the Blair Witch similarly wonder if Eileen’s drowning death was a tragic story of parental neglect. Rather than admit failure to protect this child, it’s possible that the people of Burkittsville created a story of ghostly interference similar to the parental abuse named in Monahan’s fictional retelling of the Bell Witch haunting. Though no mention was made in Myrick’s and Sánchez’s film, it’s likely that elements of this explanation made its way into the Sci-Fi mockumentary further explaining the Blair Witch legend.

Another notable similarity between these two witches is a pattern of generational repetition. The Bell Witch returns in Monyhan’s novel when Betsy’s daughter reaches the age of maturity, a subtle warning to protect her from the advances of predatory men. Though likely fictitious, this modern understanding of the legend dovetails with the power of the Blair Witch story. Falsely accused of witchcraft and murdered by a moral majority, Elly Kedward continues to warn each generation about the dangers of supernatural fear. Both legends have come to serve as cautionary tales. They reemerge with every new generation as if these wronged women are reaching out from beyond the grave. “Respect your daughters,” they say “and value the women in your life, especially those in need of protection. Dire consequences await those who fail to listen.” Regardless of the veracity of both stories, their power remains – a supernatural warning to leave women in peace.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.