Editorials

Is ‘Amityville in the Hood’ Parody or Just Kinda Racist? [The Amityville IP]

Twice a month Joe Lipsett will dissect a new Amityville Horror film to explore how the “franchise” has evolved in increasingly ludicrous directions. This is “The Amityville IP.”

There’s an uneasy tension in Amityville in the Hood (2021) between intentional parody and uncomfortable racism. How much of the film’s stereotypical depiction of Compton, which includes gangs, gun violence, drugs, and sex work, is making fun of the conventions of Hollywood films? Or is this just lazy screenwriting and uninspired scenarios?

Let’s give writer/director Dustin Ferguson the benefit of a doubt and go with the former. Of the three titles he’s made in the Amityville “franchise,” In the Hood is by far the most self-aware. There are even a few moments that play like genuine (read: intentional) comedy!

To be clear, there are still plenty of hiccups here. Like his other films in the “franchise,” Ferguson is using fairly obvious tricks to pad out the film’s runtime to feature length. This includes the usual laboriously slow credit sequence (3 minutes), a lengthy recreation of the DeFeo shooting bathed in red light and an egregious 10+ minute extended flashback to scenes from Ferguson’s previous entries, Amityville Toybox and Amityville Clownhouse.

Even with the padding, though, the credits roll at the 63-minute mark, suggesting that there’s not *quite* enough story here to fill out a feature film.

So what’s In the Hood about? Following a cold open that picks up three years after Mark Patton’s cameo in Clownhouse, a pair of gang members break into the famous New York home to steal a unique, purple-tinged crop of marijuana.

Alas this batch of weed has been cursed by the red masked figure who appeared in the previous film, which means anyone who smokes the reefer is doomed to descend into “violence, psychosis and hysteria.”

The rest of the plot loosely centers around the attempts by organized crime boss Big M (Esau McKnight) and his underlings to recover the stolen ganja in order to sell it on the street under the name “Amityville Possession.” Recurring character Peter Sommers (John R. Walker), last seen in Amityville Hex, provides sporadic Breaking News reports about the escalation of violence in the city, prompting New York Police Chief Malone (D.T Carney) to coordinate with Compton Detective White (Thom Michael Mulligan) in order to end the Amityville curse once and for all.

One of the film’s other problems, however, is the Ferguson continually loses the plot because he’s too busy introducing new peripheral characters he seems more interested in. Early on it’s brash sex worker Cheyenne (Jenn Nagle) who goes toe to toe with Big M’s bodyguard Roscoe (Erik Anthony Russo) in an extended sequence as they debate the price point for a blowjob. It’s amusing and more than a little silly, but one scene later Cheyenne is unceremoniously shot by Big M for her lazy fellatio technique. A few minutes later, Roscoe dies offscreen (!) with a handful of other characters during a crazed attack sequence. Considering the blowjob scene lasted for several minutes, in hindsight it doesn’t seem like the best use of the film’s brief runtime, particularly since none of the characters have much depth.

This happens repeatedly throughout In The Hood. It’s as though Ferguson loses interest in his characters and/or the desire to tell a coherent story. The result is a film that broadly features a city under siege from a rash of drug-induced violence, but there aren’t any characters to anchor the narrative.

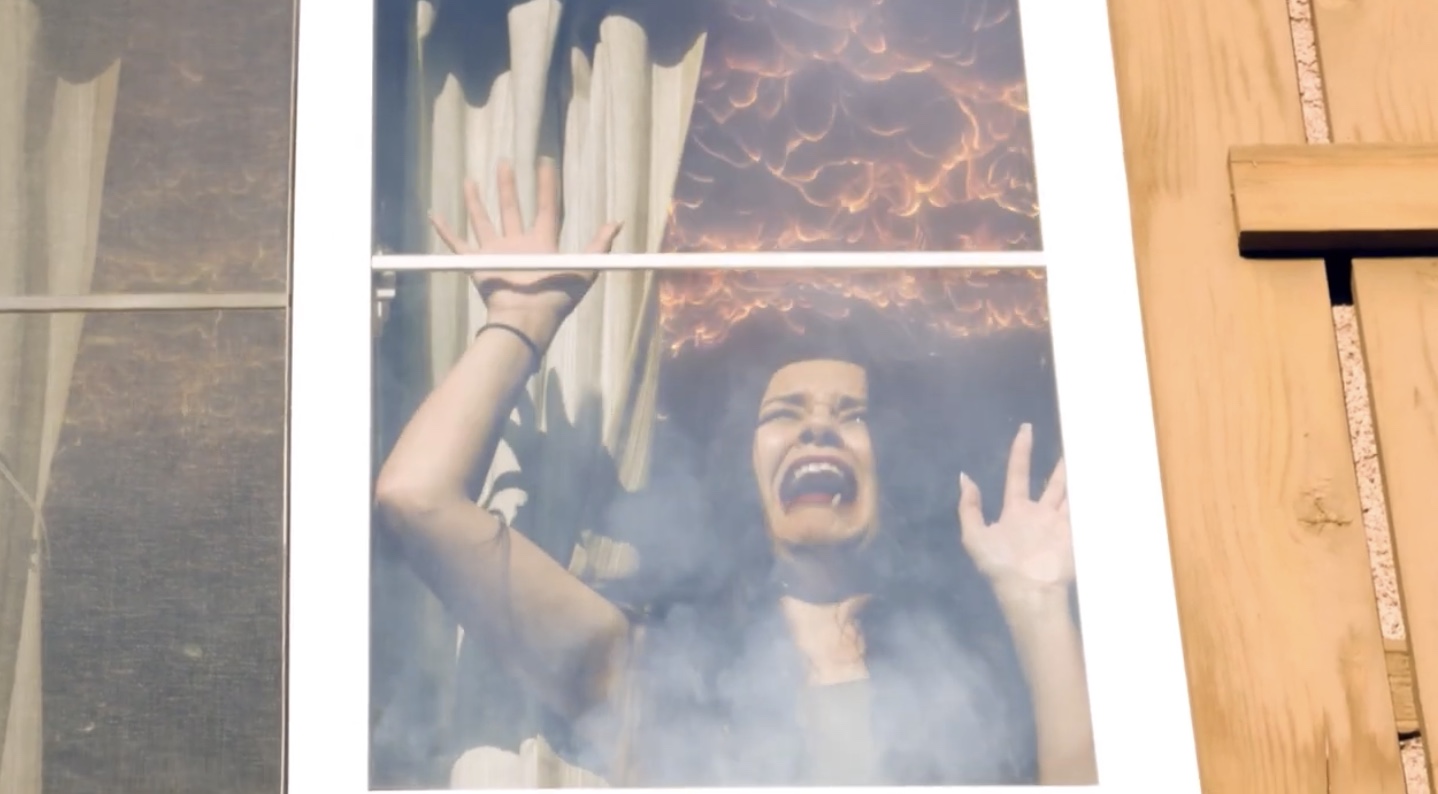

Detective White kinda/sorta eventually emerges as the protagonist when he takes it upon himself to save Sondra (Geovonna Casanova), the lone survivor of Roscoe’s massacre, then flies to New York to burn down the notorious cat-eyed house once and for all.

In reality, though, Amityville in the House plays like a loose collection of tangentially connected stories and characters, bridged by interludes from Ferguson’s other films and recurring (self-aware) montages of generic B-roll of Compton streets, under passes, and locked-up or abandoned store fronts.

If viewers buy into the idea that this is gently riffing on Hollywood films like Straight Outta Compton, In The Hood plays okay.

If not, however, the result is a repetitive, unfocused, and vaguely racist Amityville film.

The Amityville IP Awards go to…

- Rap Life: Arguably the best argument that the film is a self-aware parody is the original song “The Amityville Rap.” Written and performed by Mc Dirty D ft. Knifer, the song plays twice (once during a montage and again over the credits). Here’s a sample of the utterly ridiculous/genius lyrics: “Through the windows, you will see evil, waiting to be free. Glowing eyes in the night, in the hood, it’s a fright. Scary demon while we’re thieving, grab the stoke, then we leaving. You ain’t gang, you can’t hang. See this gun, boom bang bang.” It’s chef’s kiss perfection.

- Language Issues: One of the more frustrating elements of the film is Ferguson’s generic “street” dialogue, which is heavily reliant on swears and Black caricatures. Take, for example, Heather (Natalie Dang)’s response when she tries the new strain of pot: “Oh, this some devil shit!” Even if this is being played for comedy, it’s extremely repetitive.

- Best Diss: When Roscoe first spots Cheyenne walking up in a tight-fitting purple dress, he exclaims that she’s “Dressed up like mother*cking little Miss Mermaid and shit.”

Next time: it turns out that the Wikipedia list of titles is incomplete, so we’re circling back to a missed title with 2021’s Amityville Cop!

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.