Interviews

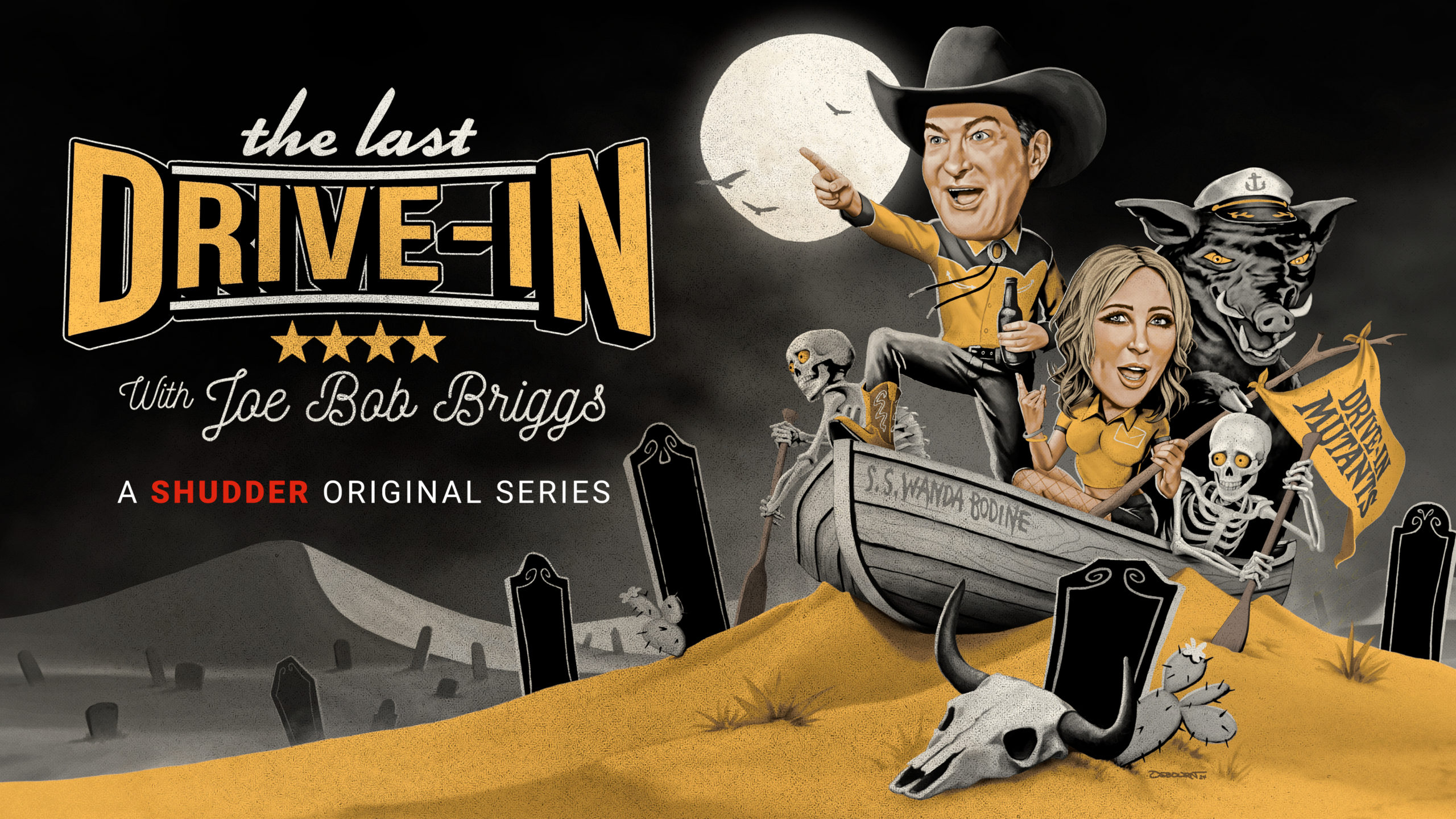

“I Don’t See Retiring from This” – Joe Bob Briggs Talks New “Last Drive-In” Format and the Show’s Future [Interview]

Hey everybody, have you heard the news? Joe Bob is back in town!

The Last Drive-In with Joe Bob Briggs has returned for its sixth season on Shudder. While the show’s format has been slightly revised — adopting a new biweekly schedule with one film instead of a double feature — the beloved horror host’s approach is much the same.

“It didn’t really change anything,” Briggs tells Bloody Disgusting. “We were crowding all of our movies into 10 weeks once a year and then having specials, and we found that people would rather have more weeks. It’s actually more movies than we had before.

“And some of the people on the East coast fall asleep in the second movie,” he laughs. “It’s about a five-hour show when it’s a double feature because we talk so much. Also, it’s hard to get thematic double features every single time. So our specials are still double features, but our regular episodes are single features.”

The season kicked off last week with The Last Drive-In Live: A Tribute to Roger Corman, celebrating the legendary filmmaker’s first 70 years in Hollywood with a double feature of 1959’s A Bucket of Blood and 1983’s Deathstalker. The special was filmed live in front of a fervent audience of Briggs’ fan base — lovingly dubbed the Mutant Family — at Joe Bob’s Drive-In Jamboree in Las Vegas last October.

In addition to his usual hosting duties, Briggs conducted a career-spanning interview with Corman and his wife, fellow producer Julie Corman. They were also joined by one of Corman’s oldest friends and collaborators, Bruce Dern. In a heartfelt moment of mutual admiration, Briggs and Corman exchanged lifetime achievement awards on hubcaps.

“I’ve known Roger for about 35 years, so I’ve only known him for half of his career,” Briggs chuckles. In his long history of reviewing, interviewing, and talking about Corman and his legendary work, one emblematic encounter sticks out to Briggs.

“I remember the very first time I went to the Corman studio, which was a lumber yard on Venice Boulevard. He had a standing set for a spaceship control room, a standing set for a strip club, and I think he had one other one, and then he had all of his editing facilities there, but it was still a lumber yard. They had not really changed any of the buildings or anything.

“He’s showing me around the studio, and we were walking past a pile of debris, and I said, ‘Roger, is that the mutant from Forbidden World?’ It had just been thrown over in a corner. And he just said, ‘Yes, Joe Bob, I believe that is. He was apparently no longer needed.’ I said, ‘Roger, you gotta get with it! That stuff is worth money.’ But he was like, ‘When the movie’s over, the movie’s over.’ That was Roget to a T.”

At least part of Corman’s longevity can be attributed to his shrewd business practices and pragmatic approach to the industry, which has included working in every conceivable genre of cinema. “I couldn’t think of a single genre he has not made,” Briggs says.

“When we did this interview at the Jamboree, I said, ‘I’m gonna name the genre, and you tell me what you love about that genre,’ and every comment that he made involved money and box office performance,” he snickers. “None of it was involved with love of cinema, although I did get him to say that his favorite genre is a genre that he didn’t dabble in much other than his first movie [1954’s Highway Dragnet], and that was film noir.”

While the fourth annual Drive-In Jamboree is still in the planning stage, Briggs is delighted by the event’s continued success. “The Jamboree is something that we literally just threw together. We’ve had three of them now. It’s something where we just show up and try to come up with programming for each day.

“But I really think the Jamboree is more about the mutant family meeting the mutant family. It’s more about people who know each other online gathering and partying with each other in person. It’s not so much about what movies we have. I mean, we always have an anniversary movie, and we always have some special guests and everything, but it’s more about the gathering of the mutants. It’s fun from that point of view. They’re exhausting, I can tell you that.”

The zeal among Briggs’ audience has only grown over the years, from hosting Joe Bob’s Drive-In Theater on The Movie Channel from 1986 to 1996, to MonsterVision on TNT from 1996 to 2000, and The Last-Drive-In on Shudder since 2018. “I’m amazed, having been in the business for this many years, that I still have a show at this time, because they say you can’t repeat TV,” Briggs notes.

“Nobody wants to see old TV, and yet I’ve done the same show three times on three different networks, and every time I try to change it everyone says, ‘No, no, don’t change it! That’s the part we love.’ I always want to do something new, and I’m always told, ‘No, you’re the CEO of Coca Cola who went to New Coke.’ You can’t do that. People will revolt. So we’re still doing it.

“It’s one of the few shows that I know of that’s just sort of grown organically over, gosh, almost 40 years. We’ve just added elements to the show. We try things. If something doesn’t work, we throw it away. If something works, we do it forever!”

The mutant family will be happy to know that Briggs plans to continue hosting and writing about movies for as long as he’s able to. “I don’t see retiring from this or retiring from writing. I’m primarily a writer, and the good thing about writing is long after they don’t wanna see you on TV anymore you can still write.

“The difference today, though, is I was pretty much the only guy doing genre films when I started. Now, there are academics that do it. There are entire books written about Dario Argento and Tobe Hooper and even lesser names than those, and there are, of course, a massive number of websites, including your own, so that when something comes out today, there’s immediately a hundred reviews of it; whereas in 1982, I was sort of the only guy, because the movies were considered disposable trash. So I have been surpassed in my deep knowledge, because who can keep up with all that? It’s impossible!”

Diana Prince, who serves as Briggs’ co-host Darcy the Mail Girl and was instrumental in getting him back in the hosting chair, has been promoted to an associate producer this season. “She was sort of always the associate producer, but I guess they finally gave her the title,” Briggs explains.

“Diana Prince is in on all the decisions about programming. I always listen to Austin Jennings, the director, and Diana Prince, the mail girl, because they come from opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of what kind of movies they wanna watch, and we try to strike a balance between. You know, she’s not gonna vote for Possession, and he’s not gonna vote for Mountaintop Motel Massacre,” he chortles.

“They’re probably the principal advisors, as far as what we show. Of course, [Diana] has a lot of social media clout, and she’s extremely knowledgeable about pop culture. Wow! She has seen everything. She’s seen more than I’ve seen!”

While surprises are part of the fun of The Last Drive-In, Briggs previews some of what’s in store this season. “The place we normally live is the neglected ’80 slasher, and we still live there,” he assures. “But we’re gonna pay a lot more attention to the ’70s especially. I’ve always thought the ’70s are more interesting than the ’80s anyway. And we’re gonna pay attention to some really recent stuff.”

He teases, “We’re gonna bring back Joe Bob’s Summer School, which is something that we used to do at MonsterVision. And we may have a marathon. There’s a possibility of that. But I’ll be digging this new format of being on every other week between now and at least up to Labor Day.”

While Briggs’ hosting format hasn’t changed much across four decades, the world around him certainly has — and that’s why The Last Drive-In remains relevant. He points out, “In the era of streaming, where everything is menus and there are thousands and thousands and thousands of choices, we are that thing called a curator that can direct you to the fun places on the spectrum of streaming.

“Streaming is very confusing for people, and a lot of people don’t like it for that reason. I hope what we’re doing is cutting through the weeds and bringing things into perspective. And, you know, it’s just more fun to watch a movie with us!” he concludes with a Texas-sized grin.

Interviews

‘I Saw the TV Glow’ – Jane Schoenbrun Talks “Buffy,” Dysphoria and Capturing the 1990s [Interview]

With We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, Jane Schoenbrun crafted an unsettling yet deeply affecting portrayal of alienation in the internet age.

Backed by A24, their sophomore feature, I Saw the TV Glow, explores similar themes of dysphoria through a wider scope without sacrificing the personal resonance.

I spoke with Schoenbrun about how the movies complement one another, recreating the 1990s on film, their love of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and more.

Bloody Disgusting: In your own words, what’s I Saw the TV Glow about?

It’s a movie about these two kids [played by Justice Smith and Brigette Lundy-Paine] stuck in the suburbs who are obsessed with the kind of TV I was obsessed with when I was a kid stuck in the suburbs, which was a trend specific to maybe the era that the movie takes place in, which is the 1990s. It’s a TV show [titled The Pink Opaque] in the vein of Buffy the Vampire Slayer that I would maybe call the “soap opera teen girls fight monsters and save the world” subgenre.

Growing up, I loved those shows. I love Buffy the Vampire Slayer in particular. I loved it so much that, in hindsight and especially as I’ve sort of come into myself as a queer and trans person, I think I clung to it as a place to put a lot of my identity; a place where I was able to exist and express a form of love or identity that I didn’t feel comfortable expressing in the environment that I was growing up and existing within.

So, in many ways, I think it’s a movie about repression. But it’s a movie that’s also speaking from within the language of those TV shows. The boundaries between the quote-unquote “real world” and this fantasy world of the show begin to bleed as the movie moves along.

BD: Did the leap in scope, budget, and resources from We’re All Going to the World’s Fair to I Saw the TV Glow affect your approach or add any pressure?

I don’t know if it added pressure. I think I was under the most pressure that I’ll ever be under making a movie when I made World’s Fair, just because it was my first time stepping into the role of director, and there was a lot of imposter syndrome to get over. I just hadn’t proven to myself that I could make a movie yet, so I think that will always be the most terrifying filmmaking experience — knock on wood! — that I ever have. But I was definitely aware of this huge leap in scope and budget, and also the system that I was operating within.

World’s Fair was a movie that I had made somewhat in isolation. We had one, single independent financier who was about as supportive a person as you can imagine. There wasn’t any worry that I wouldn’t be able to do whatever I wanted to do on that movie, and I very much cultivated that. I wanted to make my first movie in an environment that felt completely safe in that way so that I could do something uncompromised. But, on the other hand, it was a movie that I made with no resources, so it was inherently limited by the fact that, like, we couldn’t really afford more than two rooms to shoot in. [laughs]

I think I knew enough about how to make a movie, even from the beginning of that process, that I didn’t try to fight against that. I really tried to make a movie that is textually and emotionally, spiritually aligned with that kind of production reality. It’s a movie about amateur art making in a lot of ways, so making it in this outsider art kind of way made a lot of sense.

Similarly, when I started the process of setting up TV Glow, I knew it was a movie that could only be made from within a commercial landscape. I tried to think about knowing that this is going to be a different process with different benefits and different challenges. Like, what should I lean into?

For instance, this is a movie where it’s not so much about blending of like documentary and narrative forms that World’s Fair is; it’s much more about building almost like these paintings. I had the resources to create worlds and create landscapes and create the kinds of set pieces and images that were utterly out of range with the first film. I really tried to embrace that, while also still making something that — even though the form it was speaking in was a different vernacular — could still be very personal and very much something that felt like my own attempt at making an A24 movie.

BD: I think you were successful at that. Did you set out to explore a subtext of dysphoria with your films, or did it happen naturally?

With World’s Fair, it was very organic in that I knew I wanted to make work about my youth on the internet. Once I heard about the creepypasta community — which was sort of the generation below me’s version of a thing that I very much was engaged in a pre-YouTube, Flash video version of the Internet that I grew up with — I knew that I really wanted to make work about what it was about those darker corners of the Internet that I felt so drawn to as a young person.

I also knew I wanted to make work about this feeling of alienation that, at the time, I didn’t really have a word for but now I would call dysphoria. So much of that process of making that movie about a frustrated, young artist searching for identity through fiction was tangled with my own attempt at that; not as a teenager, but as somebody pushing 30.

By the time I shot the movie, I knew full well what I was talking about. I had come out to myself and had started coming out to the people around me, and I understood the movie as a text about the trans desire to find oneself through darker-toned fiction before it feels safe or comfortable or even possible to find yourself in your own body.

When I set out to make TV Glow, I really wasn’t starting from scratch. I remember very early on being like, “Great, now I have to totally start it over.” And then I was like, “No, wait. Actually, I just need to keep burrowing deeper into my obsessions and into the language that I am creating for myself as an artist.”

It wasn’t about the same thing. TV Glow is a movie that is very much reflecting on the next stage that comes after finding the language to explain this wrongness. It’s a movie about, once you’ve found that, what you do with it. It’s a movie from just on the other side of repression, reflecting on repression, its consequences, how it’s formed, and what it takes to overcome it in a space that doesn’t want you to do that.

In both cases, the movies and the way the way that I’ve learned to make things that feel personal and expansive and urgent to me as an artist, the movies are sort of interrogating whatever it is in my life that I’m fascinated by interrogating; not explaining an experience that I understand, but trying to understand an experience that I’m going through from the inside.

Over the last couple of years, that’s just been gender transition, so I think the work has very much been about that — and will probably continue to be for some time. But hopefully the work is also articulating a world view that isn’t separate from my transness, because I’m trans, but is more than just work about transness.

BD: What was your approach to capturing the 1990s in the film?

I think one of the core ideas was sort of unearthing hidden collective memories. When we think about nostalgia, when we think about the ’90s, when we think about the language of the suburbs for childhood in American film and especially in American genre film, I like to say it’s like somebody is now ripping off J.J. Abrams ripping off Steven Spielberg. These tropes of flashlights and bicycles are so overdone that they’re almost like lazy stand-ins for a feeling that once illuminated something.

In making my own work about that space, aware of that lineage, I feel like I’m really looking for ways to conjure a similar time period but in a way that feels like I’ve tapped into something that that’s a little more unseen or hasn’t been like bled of its power to the point of cliché.

A lot of the process of that on this film was just thinking about my own childhood in the suburbs and all that remained magical about it — like the inflatable planetarium that they used to bring into my like my elementary school gymnasium, or how eerie it felt going to the high school as a kid with my mom on election night to vote after hours — these little puffs of smoke that conjure a powerful feeling of another time.

The other end of that is just like being hyper-aware of the way the ’90s was being reflected back to me on television back then, and wanting to interrogate a lot of that iconography and imagery with Brandon [Tonner-Connolly], my production designer. We talked a lot about full-genre production design; this comic book-style, heightened, cartoonish landscape — like something you might see, and I love his films, in a Rob Zombie film — versus the more serious, Oscar-baby period piece production design, where everything is like trying to feel like a photograph from Time Magazine from the 1990s or something.

We talked about really trying to land right in the middle of those two extremes, so that everything could have this sort of heightened sense of unreality and candy-colored nostalgia, but could also still feel like dialed into something more restrained.

BD: Tell me a little bit about the soundtrack, which also evokes the ’90s.

I think one of the first places that that impulse came from was just remembering how big of a part of ’90s television music was; like the trope of a new band coming to play each week at the Bronze on Buffy or the Peach Pit on 90210 or Buffalo Tom for some reason playing in the hometown of the kids from My So-Called Life.

I always loved that. It was a big gateway to a lot of the music that I would come to love in my teenage years. Music was such a deep and core part of my teenage experience. Making a teen angst film, it just felt like it needed to be filled with teen angst music.

Early on in the process, I basically pitched A24 the idea of making a soundtrack from an alternate dimension, like a soundtrack that could double as the soundtrack for this TV show that never really existed. The idea was that we would get all of these contemporary bands to write the song that they would have played if they played at the Bronze on Buffy.

This was just fun for me. This was a movie studio giving me a present: getting to commission music and then work with these artists who I loved and try to be the spiritual center of a huge collaborative project where all of these individual artists were writing music that was aligned with the film and that could end up forming what I think of as a very handcrafted mixtape that I can share with folks.

It’s separate from the movie itself. I really tried to treat it as its own piece of art that was going to get made, but of course it’s tied into the movie — hopefully in the way that my favorite soundtracks can kind of exist as their own pieces of art but refer back to the movie, and then vice versa; the movie makes you want to listen to the soundtrack. This was the goal. A lot of hard and earnest work went into it with a lot of amazing artists.

BD: With Buffy being so formative for you, what was it like working with Amber Benson?

Such an honor. It was really important to me to put Amber in the movie. We reached out, and once she said she was interested in doing it, I got to chat with her about what it would mean to me, and I think to others, to put her on the screen in this particular movie and in that particular moment where she shows up. It was a deeply emotional experience, and 14-year-old me was very much there that day.

The idea of the movie having this very physical connection to my own youth, watching Tara [her Buffy character] and relating to that character and loving that character and having some unfinished business with what became of that character, getting that kind of opportunity and getting to collaborate with Amber was just deeply gratifying.

BD: The Coolidge Corner Theater in Boston is presenting you with the Breakthrough Artist Award this weekend. How does it feel to receive that kind of recognition for your work?

Super cool. I went to college in Boston and was like a 20 minute walk from the Coolidge, so I have a lot of formative memories watching horror movies there. I think at one point I even went to a Buffy the Vampire Slayer musical sing along there at like age 19. It’s really fun and sweet to return to that space.

Boston, for me, is a city that I’ll always associate with my burgeoning cinephile adolescence. I spent so much time at the Coolidge and the Brattle and the Harvard Film Archive during my years in that city. Getting an award is cool. I don’t know what to say about it. I feel so early in my artistic obsessions and pursuits. I feel in many ways still in the early stages of my hopefully long career making work that I am proud of.

The fact that it’s already resonating with folks and that it’s being recognized in all of the ways that it’s being recognized is just an amazing gift and so validating; but not just because it’s praise, but because it makes me feel optimistic about the chance to continue doing it for a long time. Ultimately, that’s the thing that makes me proudest and happiest: the idea that I can just keep doing what I love and telling stories and creating images that are deeply personal.

BD: To wrap up, why would you recommend someone seek out I Saw the TV Glow?

I think that a lot of movies that get made, and especially a lot of movies that get made these days in a commercial paradigm, it’s become increasingly rare for movies to be the personal vision and emotional articulation of an artist to an audience. To me, that’s so, so important in the work that I make.

It’s a movie that hopefully is really fun and filled with gorgeous, strange, beautiful sights and sounds; but I think it’s also a movie that comes from deep within my heart and personal experience. If you’re the type of person who looks to cinema to commune with others rather than, you know, catch the latest Marvel movie, hopefully there will be something refreshingly personal about it.

I Saw the TV Glow is currently in select theaters and will expand nationwide on May 17.

You must be logged in to post a comment.