Books

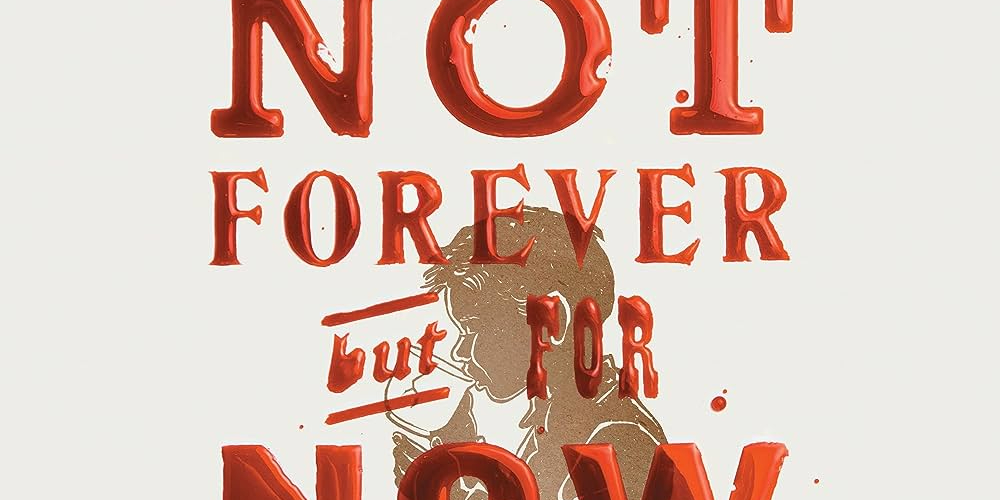

‘Not Forever, But For Now’ Book Review – Serial Killer Satire Is Chuck Palahniuk’s “Succession”

Chuck Palahniuk’s latest meditation on the haves and have-nots struggles to take a promising premise beyond surface-level shock value.

“It doesn’t matter so much who does what. The predators must prey. The prey must be predated. They only wish to be preyed upon by someone who will do the job properly.”

Chuck Palahniuk has been a top voice in subversive, satirical storytelling since the late ’90s through generation-defining texts like Fight Club, Invisible Monsters, and Choke. Palahniuk’s ability to get under society’s skin through pitch black parody and commentary on hidden subcultures has sustained a rich career that can be very hit or miss, but is at least always odd and interesting. 2007’s Rant might be Palahniuk’s last great novel, while there’s still plenty to appreciate in his works across the last decade. Not Forever, But For Now is deeply in the pocket and Palahniuk at his most ruthless and unrepentant. It’s a bold, brutal experiment that may be too much for some of Palahniuk’s most seasoned readers. That being said, it’s still a fascinating look into one of the most fearless minds in fiction.

Succession’s series finale only aired a few months ago, but rampant parodies and pastiches of this prestige program persist. Not Forever, But For Now puts its similarities to the HBO drama front and center as two siblings, Otto and Cecil, compete to take over the “family business,” which just so happens to be decades’ worth of murders and sex crimes. A power struggle within a family of serial killers over their future’s direction could be compelling. Palahniuk doesn’t do enough with this rich premise beyond its earliest ideas. In the end, Not Forever, But For Now is ultimately more The Idol than it is Succession. There’s so little story here that Not Forever, But For Now would only cover two or three episodes of television–not a full season–if it were actually a series like Succession. Intense plotting and a moving story aren’t always necessary for a good novel, which is part of the power of prose. Palahniuk has arguably done more with less in the past (Pygmy, Adjustment Day, Tell-All), but it’s not enough to properly elevate Not Forever, But For Now.

Brothers, Otto and Cecil, are terrified to be apart from one another, yet are steadily outgrowing the other and in need of independence. Despite this, they’re willing to tear down the world and get drunk on delusion in order to stay together and avoid the inevitability of adulthood. Otto and Cecil are the best and worst people for each other. There’s a toxic nature to these two–one as teacher and the other as student, like in many of Palahniuk’s stories–as they orbit one another and critique masculinity, queer culture, and high society, but never as adeptly as Palahniuk’s done in the past.

These two spend their days endlessly lost in recreations of their grandfather’s past instead of forging their own stories. It’s the ultimate example of legacy and being destined to repeat the sins of the past because in this case they’re clung to like a security blanket. This all graduates into a familial war that’s practically Shakespearean. Otto and Cecil plot to kill their grandfather, while he does the same and tries to pit these two siblings against each other, while they simultaneously fight for control of the family.

Otto and Cecil are reprehensible characters, but intentionally so. They’re written to make the reader wince and it’s difficult to spend too much time with these characters without starting to feel ill. Not Forever, But For Now anticipates that the audience will need to take short breaks in the story, which is likely part of the reason that each chapter is so short. They rarely go beyond six or seven pages, which seems to reflect the shallow nature of these characters and the repetitive cycle that consumes their lives. This approach is occasionally effective, but at 256 pages, Not Forever, But For Now is just far too long. This could have been an extremely powerful novella or short story that distills the cumbersome narrative down to one of its many similar passages rather than letting these ideas fester and spoil.

Much of Not Forever, But For Now is content to compare low-status people and one-percenters to prey and predators from a National Geographic special. These twisted siblings believe that execution of the weak is the greatest form of fealty and submission. In doing so, this family helps elevate these wasted lives into something greater in the process. It’s a thesis that has all of the pretension of Hannibal without any of the corpse art. On the contrary, these executions are blunt, messy, horrid affairs.

Not Forever, But For Now effectively taps into the public’s disdain for entitled one-percenters who feel that they don’t just run the world, but have the power to casually change it on a whim. This gets explored to exaggerated effect where the world literally bends over backwards for every one of Cecil and Otto’s selfish whims. Palahniuk’s novel even argues that there’s a parasitic relationship between humanity and existence where people are the toxin-consuming belly-feeders who soak up corruption so that the world is safe for the next generation of narcissists. It’s an ultra-egotistical circle of life that looks a lot like a noose if you squint your eyes hard enough.

Not Forever, But For Now is often evocative of A Clockwork Orange through its intense sexual acts and violence that are normalized through juvenile names and kid-speak to mask their true terrors; where rape gets reduced to playing “Winne-the-Pooh.” This can sometimes be cringe-inducing, like the detail where Otto and Cecil keep the “pussy fingers” of their celebrity psy-op executions as mementos. However, Palahniuk occasionally taps into an odd beauty with its endless sex and violence. There’s a really evocative chapter about a body of water that’s full of endless women and discarded corpses that’s mounted up over time like a subterranean sandcastle. Like any actual sandcastle, Not Forever, But For Now has too weak of a foundation that begins to crumble the more that Palahniuk plays with it.

Otto and Cecil’s regressive acts spin their wheels until Not Forever, But For Now culminates with the advent of a predatory app, Tyger, where middle-class ordinary people gain the “privilege” to do themselves in instead of this being an exit act that’s purely experienced by the one-percenters. It’s almost like if Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery was reinterpreted by a social media influencer millennial. Not Forever, But For Now is easily the most alive in this final part (the novel is divided into three sections) when Otto and Cecil finally go off and embrace the family business.

Palahniuk, like in many of his novels, teases his audience through unreliable narrators who omit major parts of the story so as to alter the reader’s perception of Otto and Cecil. That being said, Not Forever, But For Now becomes that much more interesting if the audience is left to wrestle with these probable suspicions throughout the story. Instead, readers are forced to dispose of these thoughts almost immediately after they’re introduced due to the structure that the novel does take. It sacrifices a novel’s worth of tension for a quick lark and surprise.

Despite all of this free-floating nihilism, Not Forever, But For Now does end on an optimistic, encouraging note. One that doesn’t necessarily redeem this work of fiction, but does still leave the reader with positive values rather than a sick taste in their mouth. Many may view this as too little too late, but it’s an important distinction that changes the novel’s themes and values in crucial ways that will hopefully make the audience want to re-read the novel from the beginning rather than never pick it up again. Not Forever, But For Now is vintage Palahniuk, for both better and for worse. It’s not the comeback novel that many fans are hoping it will be, but it’s still an ultra-timely story that holds a funhouse mirror up to modern society–one just needs to look past all of the blood, guts, and bodily fluids that are caked onto the reflection.

‘Not Forever, But For Now’ is published by Simon & Schuster and available now.

Books

‘Halloween: Illustrated’ Review: Original Novelization of John Carpenter’s Classic Gets an Upgrade

Film novelizations have existed for over 100 years, dating back to the silent era, but they peaked in popularity in the ’70s and ’80s, following the advent of the modern blockbuster but prior to the rise of home video. Despite many beloved properties receiving novelizations upon release, a perceived lack of interest have left a majority of them out of print for decades, with desirable titles attracting three figures on the secondary market.

Once such highly sought-after novelization is that of Halloween by Richard Curtis (under the pen name Curtis Richards), based on the screenplay by John Carpenter and Debra Hill. Originally published in 1979 by Bantam Books, the mass market paperback was reissued in the early ’80s but has been out of print for over 40 years.

But even in book form, you can’t kill the boogeyman. While a simple reprint would have satisfied the fanbase, boutique publisher Printed in Blood has gone above and beyond by turning the Halloween novelization into a coffee table book. Curtis’ unabridged original text is accompanied by nearly 100 new pieces of artwork by Orlando Arocena to create Halloween: Illustrated.

One of the reasons that The Shape is so scary is because he is, as Dr. Loomis eloquently puts it, “purely and simply evil.” Like the film sequels that would follow, the novelization attempts to give reason to the malevolence. More ambiguous than his sister or a cult, Curtis’ prologue ties Michael’s preternatural abilities to an ancient Celtic curse.

Jumping to 1963, the first few chapters delve into Michael’s childhood. Curtis hints at a familial history of evil by introducing a dogmatic grandmother, a concerned mother, and a 6-year-old boy plagued by violent nightmares and voices. The author also provides glimpses at Michael’s trial and his time at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, which not only strengthens Loomis’ motivation for keeping him institutionalized but also provides a more concrete theory on how Michael learned to drive.

Aside from a handful of minor discrepancies, including Laurie stabbing Michael in his manhood, the rest of the book essentially follows the film’s depiction of that fateful Halloween night in 1978 beat for beat. Some of the writing is dated — like a smutty fixation on every female character’s breasts and a casual use of the R-word — but it otherwise possesses a timelessness similar to its film counterpart. The written version benefits from expanded detail and enriched characters.

The addition of Arocena’s stunning illustrations, some of which are integrated into the text, creates a unique reading experience. The artwork has a painterly quality to it but is made digitally using vectors. He faithfully reproduces many of Halloween‘s most memorable moments, down to actor likeness, but his more expressionistic pieces are particularly striking.

The 224-page hardcover tome also includes an introduction by Curtis — who details the challenges of translating a script into a novel and explains the reasoning behind his decisions to occasionally subvert the source material — and a brief afterword from Arocena.

Novelizations allow readers to revisit worlds they love from a different perspective. It’s impossible to divorce Halloween from the film’s iconography — Carpenter’s atmospheric direction and score, Dean Cundey’s anamorphic cinematography, Michael’s expressionless mask, Jamie Lee Curtis’ star-making performance — but Halloween: Illustrated paints a vivid picture in the mind’s eye through Curtis’ writing and Arocena’s artwork.

Halloween: Illustrated is available now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.