Editorials

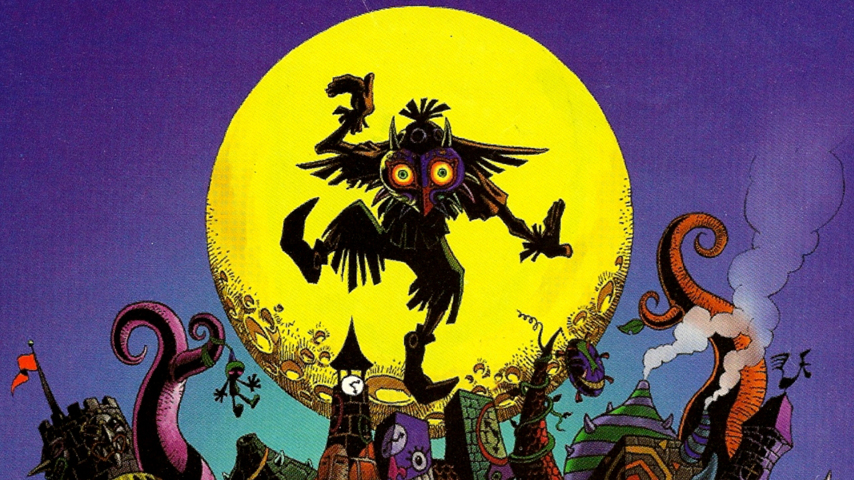

20 Years On, ‘The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask’ is Still Link’s Darkest Adventure

The Legend of Zelda has become one of the most captivating fantasy experiences in all of video game history. At the core of its story has always been a young boy fighting against evil, traversing an immense land brimming with excitement. But in the year 2000, something very different took place in the franchise. Two years after the iconic release of Ocarina of Time, The Legend of Zelda would follow up with its next installment for the Nintendo 64, Majora’s Mask.

Picking up after the events of Ocarina of Time, the story opens with Link searching for his fairy companion Navi. As he rides his horse Epona, the woods around them permeate with gloom. The two are ambushed by two fairies and a Skull Kid; the latter is a woodland being of sorts in the Zelda games. What immediately stands out about Skull Kid is his mask; with its heart-shaped design, vibrant colors, and other eccentric features, the mask exudes a mystic appeal.

Skull Kid steals Link’s ocarina and Epona. Chasing after Skull Kid, Link enters a tree, stumbling and falling down a large black hole (kicking off this Alice In Wonderland-esque sequence). Skull Kid uses magic to transform Link into a plant-based creature known as a Deku, escaping with one of the fairies. The remaining fairy, Tatl, stays with Link and works with him to find Skull Kid.

Making their way to the land of Termina, Link and Tatl come into contact with the Happy Mask Salesman, who requests that Link retrieve the mask Skull Kid is wearing. After this conversation, Link and Tatl explore Clock Town in pursuit of Skull Kid. When the duo finally confront him, they realize that he is no longer in control of his actions – but that the mask is possessing him. The mask intends to use the moon to destroy Termina; just as the moon is about to crash into Clock Town, Link performs “The Song of Time”, sending him and Tatl back in time. The two find themselves back where they started when first entering Clock Town. When they meet up with the Happy Mask Salesman again, he tells them about the evil power that is Majora’s Mask. From there, Link sets out on a quest to defeat Majora.

Majora’s Mask is easily one of the more unique titles among The Legend of Zelda franchise. For one, while Ocarina of Time involved time travel, Majora’s Mask brings an intriguing twist to the mechanic. The majority of the game’s narrative follows a 72 hour period; at the end of that timeframe, the moon will crash down upon Termina (presenting an immediate game over). To prevent this, and regardless of where Link is on his journey, “The Song of Time” will have to be played to reverse time. This in itself is an interesting element to a Zelda game; imagine being in the middle of a dungeon and having to reverse time and start over. Link will be able to hold onto key items, but any rupees and dungeon keys that may be on him will be lost when restarting back in Clock Town.

Another awesome component to the game is that of the masks Link can collect and wear. Many of these masks include special abilities. Among all the masks Link can find, there are three central to the game’s story: the Deku, Goron, and Zora masks. Each of these allows Link to transform his being, offering the chance to use abilities associated with that race. As a Deku, Link can enter and pop out of special flowers to glide for a brief period of time; the Goron mask allows Link to use a special roll attack, while the Zora mask allows him to breathe and use magic underwater. As part of Link’s adventuring tools, these masks present exciting ways for him to approach various objectives.

However, what truly makes Majora’s Mask so brilliant is its atmosphere and emotional narrative.

Looking back at past Zelda experiences, the closest the games have ever gotten to horror is that of their creatures and dungeons. In particular, there’s the terrific Shadow Temple in Ocarina of Time and its chilling boss monster Bongo Bongo, as well as the Forest Temple and its boss Phantom Gannon. And while Twilight Princess also dwells in some ominous tones, Majora’s Mask is the Zelda experience to lean most heavily into horror. Beyond its use of monsters and creepy dungeons, however, the real horror of Majora’s Mask is that of the psychological.

From the moment Link falls down that Alice In Wonderland-like hole, there is a consistent weird aura surrounding the world of Termina. There are several NPCs throughout the game who come across as off-kilter; from wacky dialogue to bizarre behavior, many of Termina’s inhabitants are surreal. Similar to the murkiness found in the “future portion” of Ocarina of Time, the respective dungeons of Majora’s Mask linger with nightmarish appeal. While the aforementioned Bongo Bongo and Phantom Gannon make for chilling boss encounters in Ocarina of Time, each of the bosses found in Majora’s Mask bring their own eerie tension. Personally, I’ll never forget Goht; as a giant mechanical goat being with a mask resembling a human face, I found its figure to be unsettling.

Even traveling throughout the land of Termina comes with a sense of unease. Whereas Ocarina of Time has moments of delightful high fantasy adventure, Termina feels uncomfortable and grim. And of course, we can’t forget about the undeniably haunting moon and its menacing facial expression. As Link continues through his 72-hour journey, the moon’s eerie eyes and disturbing grim will always be found staring down at the land.

But while these various elements contribute to the creepy atmosphere, it’s the game’s narrative and themes that further elevate the use of psychological horror. While not officially confirmed by anyone at Nintendo, there are several articles and fan theories that point to much deeper, more ominous readings of Majora’s Mask – such as the world of Termina representing the various stages of grief and that Link might be dead.

When you breakdown each of the main locales Link visits, each of them reflects a stage of the Kübler-Ross model of grief. The stages involve Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance.

Some of the people in Clock Town deny that the moon is descending closer; the Deku villagers in Woodfall are angry at a monkey who they blame for kidnapping their princess; a Goron ghost in Snowhead bargains with Link to revive him; Lulu from The Great Bay region exhibits symptoms of depression in regards to her stolen eggs; and in Ikana Canyon, Link must climb the Stone Tower Temple and eventually find the Light Arrows (climbing this structure and obtaining “light” can be read as a means of “ascending towards acceptance”).

In regards to the notion that Link may be dead, there is one theory that particularly interests me. Upon chasing Skull Kid and falling down that hole, Link has died and the rest of the game represents him working through his own purgatory.

If one looks at Majora’s Mask through this lens, then Link’s adventure takes on an entirely different context; no longer is the game solely about a boy fighting against evil, it is about a boy trying to overcome his despair. The presence of grief also lingers among some of the game’s NPCs; Link will come across a variety of NPCs who will express personal woes. Each of these characters involve different emotional depths, all adding to the game’s somber nature. Even the whole concept of reversing time and reliving the same 72 hour period feels very on point with themes of grief and despair; grieving can feel cyclical at times while one is trying to heal.

Yet in each darkness Link faces head-on, he brings a little more brightness to the world of Termina – his perseverance also leads to him finding hope and solace. The inhabitants of Termina eventually come to discover their own form of acceptance as well. For a game with so many external thrills, Majora’s Mask makes for a very intimate telling about internal suffering and healing.

It goes without saying that The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask is an experience unlike any other among The Legend of Zelda franchise. While the time travel and masks make for interesting mechanics, the game’s presentation is what allows it to shine. Whereas some games strive to hit players with over the top horror imagery, Majora’s Mask works in a more subtle manner. The horror of Majora’s Mask is that of lingering dread.

The world design, atmosphere, surreal characters, and emotional story all come together for one of Link’s darkest adventures. With it being 20 years since its release, The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask remains one of the most fascinating and chilling experiences among contemporary gaming.

Editorials

‘Immaculate’ – A Companion Watch Guide to the Religious Horror Movie and Its Cinematic Influences

The religious horror movie Immaculate, starring Sydney Sweeney and directed by Michael Mohan, wears its horror influences on its sleeves. NEON’s new horror movie is now available on Digital and PVOD, making it easier to catch up with the buzzy title. If you’ve already seen Immaculate, this companion watch guide highlights horror movies to pair with it.

Sweeney stars in Immaculate as Cecilia, a woman of devout faith who is offered a fulfilling new role at an illustrious Italian convent. Cecilia’s warm welcome to the picture-perfect Italian countryside gets derailed soon enough when she discovers she’s become pregnant and realizes the convent harbors disturbing secrets.

From Will Bates’ gothic score to the filming locations and even shot compositions, Immaculate owes a lot to its cinematic influences. Mohan pulls from more than just religious horror, though. While Immaculate pays tribute to the classics, the horror movie surprises for the way it leans so heavily into Italian horror and New French Extremity. Let’s dig into many of the film’s most prominent horror influences with a companion watch guide.

Warning: Immaculate spoilers ahead.

Rosemary’s Baby

!['Rosemary's Baby' - Is Paramount's 'Apartment 7A' a Secret Remake?! [Exclusive]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Rosemarys-Baby.jpeg?resize=740%2C416&ssl=1)

The mother of all pregnancy horror movies introduces Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow), an eager-to-please housewife who’s supportive of her husband, Guy, and thrilled he landed them a spot in the coveted Bramford apartment building. Guy proposes a romantic evening, which gives way to a hallucinogenic nightmare scenario that leaves Rosemary confused and pregnant. Rosemary’s suspicions and paranoia mount as she’s gaslit by everyone around her, all attempting to distract her from her deeply abnormal pregnancy. While Cecilia follows a similar emotional journey to Rosemary, from the confusion over her baby’s conception to being gaslit by those who claim to have her best interests in mind, Immaculate inverts the iconic final frame of Rosemary’s Baby to great effect.

The Exorcist

William Friedkin’s horror classic shook audiences to their core upon release in the ’70s, largely for its shocking imagery. A grim battle over faith is waged between demon Pazuzu and priests Damien Karras (Jason Miller) and Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow). The battleground happens to be a 12-year-old, Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair), whose possessed form commits blasphemy often, including violently masturbating with a crucifix. Yet Friedkin captures the horrifying events with stunning cinematography; the emotional complexity and shot composition lend elegance to a film that counterbalances the horror. That balance between transgressive imagery and artful form permeates Immaculate as well.

Suspiria

Jessica Harper stars as Suzy Bannion, an American newcomer at a prestigious dance academy in Germany who uncovers a supernatural conspiracy amid a series of grisly murders. It’s a dance academy so disciplined in its art form that its students and faculty live their full time, spending nearly every waking hour there, including built-in meals and scheduled bedtimes. Like Suzy Bannion, Cecilia is a novitiate committed to learning her chosen trade, so much so that she travels to a foreign country to continue her training. Also, like Suzy, Cecilia quickly realizes the pristine façade of her new setting belies sinister secrets that mean her harm.

What Have You Done to Solange?

This 1972 Italian horror film follows a college professor who gets embroiled in a bizarre series of murders when his mistress, a student, witnesses one taking place. The professor starts his own investigation to discover what happened to the young woman, Solange. Sex, murder, and religion course through this Giallo’s veins, which features I Spit on Your Grave’s Camille Keaton as Solange. Immaculate director Michael Mohan revealed to The Wrap that he emulated director Massimo Dallamano’s techniques, particularly in a key scene that sees Cecilia alone in a crowded room of male superiors, all interrogating her on her immaculate status.

The Red Queen Kills Seven Times

In this Giallo, two sisters inherit their family’s castle that’s also cursed. When a dark-haired, red-robed woman begins killing people around them, the sisters begin to wonder if the castle’s mysterious curse has resurfaced. Director Emilio Miraglia infuses his Giallo with vibrant style, with the titular Red Queen instantly eye-catching in design. While the killer’s design and use of red no doubt played an influential role in some of Immaculate’s nightmare imagery, its biggest inspiration in Mohan’s film is its score. Immaculate pays tribute to The Red Queen Kills Seven Times through specific music cues.

The Vanishing

Rex’s life is irrevocably changed when the love of his life is abducted from a rest stop. Three years later, he begins receiving letters from his girlfriend’s abductor. Director George Sluizer infuses his simple premise with bone-chilling dread and psychological terror as the kidnapper toys with Red. It builds to a harrowing finale you won’t forget; and neither did Mohan, who cited The Vanishing as an influence on Immaculate. Likely for its surprise closing moments, but mostly for the way Sluizer filmed from inside a coffin.

The Other Hell

This nunsploitation film begins where Immaculate ends: in the catacombs of a convent that leads to an underground laboratory. The Other Hell sees a priest investigating the seemingly paranormal activity surrounding the convent as possessed nuns get violent toward others. But is this a case of the Devil or simply nuns run amok? Immaculate opts to ground its horrors in reality, where The Other Hell leans into the supernatural, but the surprise lab setting beneath the holy grounds evokes the same sense of blasphemous shock.

Inside

During Immaculate‘s freakout climax, Cecilia sets the underground lab on fire with Father Sal Tedeschi (Álvaro Morte) locked inside. He manages to escape, though badly burned, and chases Cecilia through the catacombs. When Father Tedeschi catches Cecilia, he attempts to cut her baby out of her womb, and the stark imagery instantly calls Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury’s seminal French horror movie to mind. Like Tedeschi, Inside’s La Femme (Béatrice Dalle) will stop at nothing to get the baby, badly burned and all.

Burial Ground

At first glance, this Italian zombie movie bears little resemblance to Immaculate. The plot sees an eclectic group forced to band together against a wave of undead, offering no shortage of zombie gore and wild character quirks. What connects them is the setting; both employed the Villa Parisi as a filming location. The Villa Parisi happens to be a prominent filming spot for Italian horror; also pair the new horror movie with Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood or Blood for Dracula for additional boundary-pushing horror titles shot at the Villa Parisi.

The Devils

The Devils was always intended to be incendiary. Horror, at its most depraved and sadistic, tends to make casual viewers uncomfortable. Ken Russell’s 1971 epic takes it to a whole new squeamish level with its nightmarish visuals steeped in some historical accuracy. There are the horror classics, like The Exorcist, and there are definitive transgressive horror cult classics. The Devils falls squarely in the latter, and Russell’s fearlessness in exploring taboos and wielding unholy imagery inspired Mohan’s approach to the escalating horror in Immaculate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.