Editorials

‘Silent Hill’: Looking Back on the Groundbreaking Classic 25 Years Later

Metal Gear Solid on the original PlayStation was the first time I actually remember being plugged into the hype cycle of a video game. I was in my early teens and finally really getting into the hobby, reading various magazines and taking in all the information I could about the industry. When I got the game, I had an amazing time with it, but despite how focused I was on it, I couldn’t stop thinking about something I saw on the back of the instruction manual: an ad that said “Coming Soon” with a crossed-arm cop, alongside the text “Welcome to Hell” and the title Silent Hill. It gave me nothing about the contents of the actual game, but I was drawn to it. Maybe there was something transgressive to my young mind about seeing a ‘bad word’ like Hell prominently in an advertisement, maybe it was just the vibe of the name “Silent Hill,” but it grabbed me immediately. When new gaming magazines arrived with details on the game, I ate them up and wanted more. No matter how much I learned about the game, it did not prepare me for how it would change the trajectory of my genre interest going forward.

I was familiar with the feeling of being scared in a video game from playing Resident Evil, but Silent Hill was something else. While Resident Evil pushed the boundary of gore in startling ways, Silent Hill unsettled me in ways I wasn’t used to. In Silent Hill, you were cast as a novelist looking for his daughter in a shifting nightmare town where anything could happen, a far cry from the prepared badasses of S.T.A.R.S. who were braving the undead horrors of Spencer Mansion, making the tension feel more real and grounded as things got strange around you.

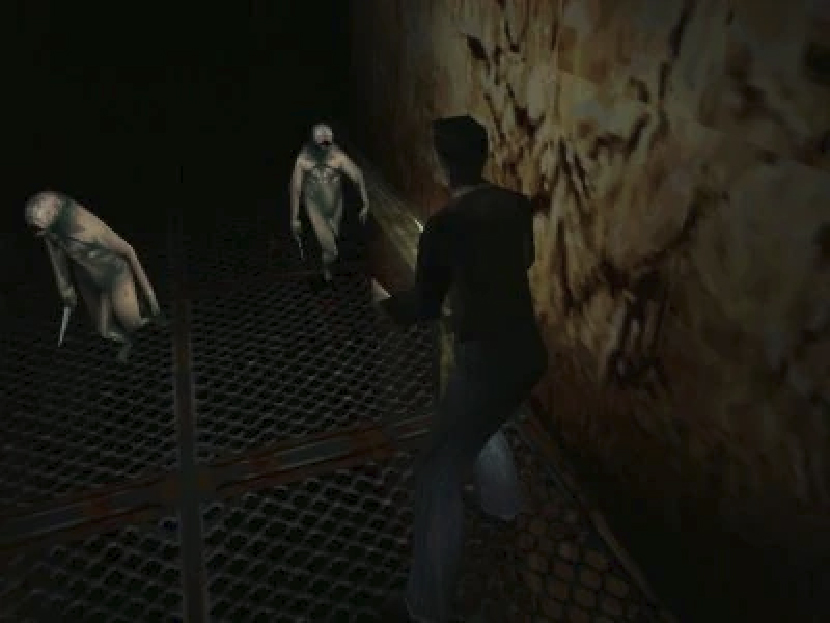

The opening of the game immediately demonstrates this combination of disempowerment and unpredictability. You, as Harry Mason, are following your daughter through the foggy streets of Silent Hill, catching glimpses of her just at the edge of your vision. Eventually, her trail leads you down an alleyway. As you progress, shifting between dynamic preset camera angles, the world slowly gets darker until you are walking around illuminated only by a lit match. A broken wheelchair, a hospital gurney with a body under a sheet, and a path of blood all lead you to the horrific sight of a skinned body hanging in barbed wire at the end of the alley. Before you have a moment to process what’s in front of you, child-sized creatures with knives descend upon you. You have no way of fighting back, and going back the way you came will bring you to a dead end. The only way to progress is to die.

In the next scene, you wake up in an abandoned diner with the cop from the previously mentioned advertisement. There’s never really any explanation given to what just happened to you, but it sets the expectations for what you’re going to experience over the game for the next seven or so hours. Metal Gear Solid had shown me that the medium could tell more serious stories in the vein of what I expected in films, and Silent Hill was the first horror game to attempt that level of seriousness for me. While Resident Evil definitely felt mature in content, pushing violence, Silent Hill felt mature in theme, challenging me with ideas I never expected from a video game. The surreal tone kept me constantly on edge, allowing the game to truly get under my skin.

Not only did the game push the horror narrative for the time, it also felt like a technological leap. Resident Evil looked great by using pre-rendered images as backgrounds combined with well-thought-out fixed camera angles. By contrast, Silent Hill rendered its environment in full 3D, allowing them to mix fixed camera angles with a more dynamic point of view. Full 3D allowed the perspective to move with the player when it needs to, making for a more kinetic experience without losing the handcrafted framing when needed. Even the technical limitations of the console gave the game its most iconic visual element: the fog. Limited visibility kept everything tense as your radio altered you of monsters just outside your range of vision. Navigating the darkness was equally fraught, giving you only your trusty flashlight to light the way.

Some of my favorite gaming memories were playing Silent Hill with my buddies. While we traditionally played multiplayer games, Silent Hill was a game where we could play by passing the controller around, leaving the others to watch. We played in full darkness at night to set the mood in the gaming area of our basement. There was an element of bravery to it, seeing who could play for the longest before they had to hand it off to someone else. We’d even challenge each other to turn off the radio so there was no static to warn us of nearby creatures. The game’s clever puzzles provided us with a unique opportunity to turn a single player game into something of a co-op multiplayer game by forcing us to collectively work together to figure out the solutions. It became a tradition for us to do this with other single player games, but none of them were as memorable as our time with Silent Hill.

My enjoyment of Silent Hill led me to the discovery of a lot of my favorite media. After reading interviews with the developers, I started to dig into the filmography of David Lynch, who they cited as one of their influences. Since then, Lynch has been one of my favorite filmmakers, both as a talented director and a fun personality. When the Silent Hill series was at its height, I was starting to discover internet forums and spent a lot of time reading through a Silent Hill website, and recommendations from users there pointed me to my all-time favorite novel House of Leaves. Chasing the tone of Silent Hill is something I’m always doing, so even to this day I check out almost anything that even vaguely reminds me of the series.

All of the entries I played (I skipped Origins, Homecoming, Shattered Memories and Downpour) have their merits, with Silent Hill 2 and P.T. being my favorites, but I have such a strong attachment to the first for its place in my personal gaming history. It’s certainly been a ride to be a fan of the series, with the cancellation of P.T./Silent Hills and constant false rumors of its “secret” revival. A little over a year ago, we finally got concrete plans for the return of the series, but like most fans, I’m still hesitant. Ascension kicked off this new era with an extremely rocky start, and I find the remake of Silent Hill 2 to be largely unnecessary for what is already basically a perfect game. Silent Hill: Townfall and Silent Hill f both look to be doing something fresh and unique with the series, but we still have yet to hear much about either of them since their reveal.

Even if none of the new games turn out to be good, I’ll always have the comfort of being able to return to the beloved originals. At this point, I’m not really searching for the next game in the Silent Hill series, but rather the next thing that captures the feeling of sitting in a dark room with my friends, playing the scariest game we’d ever seen.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.