Editorials

40 Years Later and ‘The Hills Still Have Eyes’

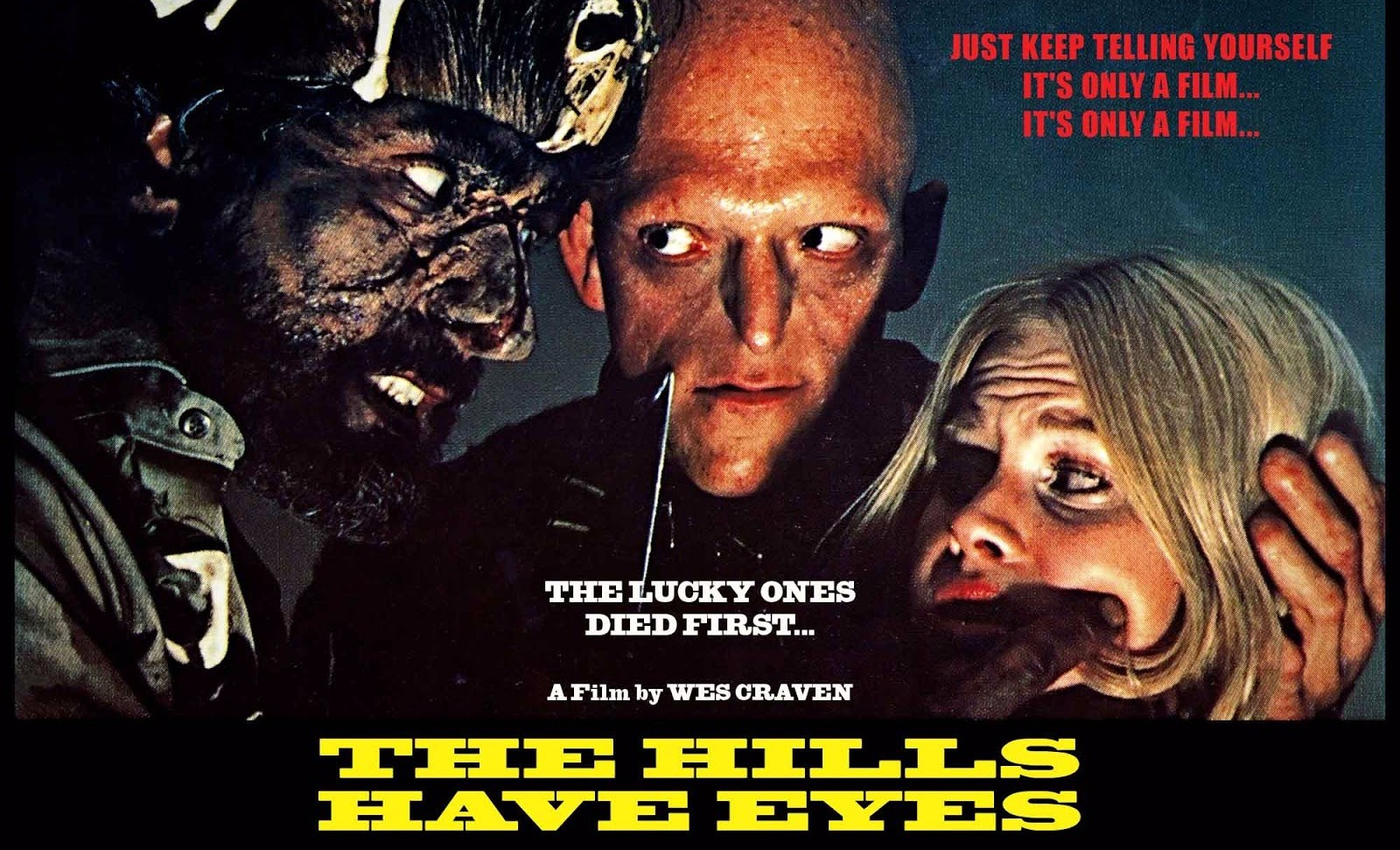

40 years ago today, Wes Craven unleashed his follow-up to the grim and nasty Last House on the Left with the equally grim and nasty The Hills Have Eyes. Hesitant to dive into another exploitation flick, Craven eventually came around to persistent urgings from the film’s producer, Peter Locke. And as if Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was nothing more than a dare, Craven crafted Hills with a similar hysterical energy, upping the gore quotient and tossing in an innocent baby for demented measure. The two films share many similarities, not just in plot but crew as well. Craven’s survival horror yarn doesn’t shy away from rough subject matter, and unsurprisingly, the production itself was no cakewalk. Despite the struggles the cast and crew may have weathered to get the damn thing “in the can”, it all paid off in the end. To steal a tag from Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast, “There’s nothing so appalling in the annals of horror!”

Spoiler Warning!

Blood Relations

Last House (1972) was Craven’s first feature as a director. He aspired to create something different in his sophomore effort, something outside the horror genre. Producers weren’t interested in what he was selling, however, unless it featured a little blood and depravity. A close friend of Craven, Peter Locke, had some money and wanted to funnel it into a horror picture. Finally, “I was broke,” Craven has stated, so he got to work on a new horror script. The writer/director took a great deal of inspiration from the purported case of the Sawny Bean Clan. From the lore’s Wikipedia page:

“Sawney” Bean was said to be the head of a 48-member clan in Scotland anywhere between the 13th and 16th centuries, reportedly executed for the mass murder and cannibalisation of over 1,000 people.”

While the obvious connective tissue is there (feral cannibal family), it was the treatment of the Bean Clan after their capture that proved interest to Craven. After finally being hunted down and arrested, the entire family was slowly tortured by burning, quartering, hanging, and more. The filmmaker was struck by the parallel between the cave-dwelling cannibals and the animalistic revenge meted out by more “civilized” people. A script entitled Blood Relations was born.

Eyeing a Massacre

Only three years had passed since Hooper’s TCM came along and blew up the indie scene. Wes Craven certainly wasn’t a stranger to the film and was open about the fact. He’s stated he was crafting a bit of an homage to the grindhouse classic. I’d say that’s blatantly obvious. Though, there are some who would prefer to call Hills a straight “rip off.” Certainly the plot is colored in several shades of Chainsaw. A family on vacation cuts through a barren desert in hopes of coming upon an old silver mine. After wrecking their car, they’re now stranded in the wide open nowhere and must protect themselves against a tightly knit family of cannibals. Both films even feature their own take on the “gas station of doom”. In all fairness, however, TCM is likely the originator of said trope.

Production designer Robert Burns actually worked on each film. The home of the clan in Hills was decorated with numerous bones, animal hides, and various knick knacks that were carried over from the set of TCM! The two films will always be linked as early examples of extreme survival horror. That said, I have, perhaps, a controversial opinion on the matter. Hooper’s film is a genuine masterpiece of gut-wrenching, grounded terror, but I’ve always prefered The Hills Have Eyes. Maybe that’s blasphemous to say, but no matter how many times I’ve seen it, I find the tension Craven builds to be overwhelming…and my eyes always end up watering up at least once (more on that later).

So, sure, in terms of tone, both films feel hot, sweaty, and covered in dirt. There’s a genuine discomfort felt in the actors’ performances which is palpable, mostly due to the fact they were uncomfortable given the exhausting shooting conditions. It’s interesting to note the style of Hills is inline with that of Craven’s first feature. Last House was an ultra low budget, lean-mean exploitation machine. With that in mind, it’s hard to call Craven a thief in terms of style. Considering Last House was released in 72′, who copied who? At the end of the day, these are two distinct filmmakers with their own claim to genre fame, so no one was really aping anyone. It was the late 70’s and these two filmmakers were at the forefront of the type of grindhouse horror cinema that was about to explode into mainstream culture within the next decade,

Sick and Depraved

With temperatures upwards of 120 degrees during the day and as low as 30 at night, it was a difficult shoot for everyone involved. The budget was around 300k. That’s about 3x as much as Craven had on Last House, but it still meant that people were scraping by to get the film finished. There were no luxuries, a lot of the actors were doing their own makeup, and Dee Wallace quasi-jokingly stated the dogs (Beauty and Beast) were treated better than anyone else on set. The entire cast was drained from their physically demanding roles after clocking in 6 day work weeks ranging from 12 to 14 hours a day. Apparently when the clan is devouring some char-grilled Big Bob around the fire, the actors were starving. The fake human flesh was actually a leg of lamb roast. As repulsive as the idea of cannibalism was to them, it was actually a treat to “play pretend” for that particular scene.

According to Craven, a majority of the crew were made up of Roger Corman regulars . They’d apparently come straight from wrapping a production with Corman to the set of Hills. They were a surly, tired bunch. Craven believes they changed their tune a few weeks in after realizing what they were doing was something special. The Hills Have Eyes wasn’t going to be just another quickie cash grab. The young director’s enthusiasm was beginning to rub off. The producer was enthusiastic as well, he just channeled the energy a tad differently. Locke was always on set, rushing Craven to keep shooting. After all, this was his money on the line. He needed to ensure there was a finished product to show off at the end of the day. Of course, when he wasn’t barking behind the cameras, he was hamming it up on screen. Locke begged Wes to throw him a cameo role. The little seen member of the clan, Mercury (credited to Arthur King), who seemed to think eating a baby’s tongue was hilarious, was actually the producer himself.

Speaking of the baby, we all know that lil’ cutie-pie survives to see the end credits roll. That wasn’t always the plan, however. Craven was contemplating having baby Kathy wind up as an amuse-bouche for Papa Jupiter. The majority of the cast revolted against the idea. Michael Berryman (the iconic Pluto) stated if it came to it, he would refuse to do the scene. Craven eventually acquiesced, and baby Kathy remained off the menu. That’s not to say the film holds back in any other regard. The most impactful sequence of the film revolves around the clan’s initial assault onto the family’s tractor-trailer. One moment after the next is a flurry of brutal violence. The scene comes to a head with the pull of a trigger, empty of bullets and a threat. I always feel the need to steady my breathing after this scene. It’s one of the reasons a concerned mother during an early screening shouted out, “This movie is sick and depraved!” Unbeknownst to her, in the next row sat Michael Berryman. He politely tapped the woman on her shoulder and stated, “You damn right, lady.”

The Hills Have Legs

The film’s title, Blood Relations, didn’t seem to be going over well. So, out of a hat of a hundred odd names, the winner was The Hills Have Eyes. Craven wasn’t crazy about the new title, but it tested well. In the 40 years since the film was released, The Hills Have Eyes has amassed quite the large following. It’s hard to throw a rock at any decent horror convention without clocking someone involved with the film’s production in the head. Obviously, gorehounds flock to the film for the few but wonderfully staged moments of brutality. Others manage to relate not to the wholesome family at the center of the story but instead to the cannibalistic loonies on the fringes. Thrill seekers enjoy the catharsis of seeing the beaten down survivors fight back and take down the bad guys one by one. Of course, everyone loves Wes Craven’s MacGyver-esque antics as well. To me, the reason the film has had such a lasting legacy is the strength of the characters.

Craven molded the Carters after his own family and neighbors, and that familiarity shines through the screen. I see my mother and father so clearly in Ethel and Bob Carter, and it hurts watching the fate that befalls the patriarchs of this everyday family unit. I seriously get a bit teary eyed when Ethel has her breakdown upon discovering Bob’s burnt body. It’s tough to watch, and even more difficult still when Doug attempts to comfort her as her life slowly slips away. It’s these moments of true horror that make the finale so satisfying. The closing note is certainly no stereotypical happy ending (unlike the more traditional alternate ending rejected by Craven).

Bobby and Brenda are jumping up and down as if they just won a contest after bloodily dispatching of Papa Jupiter. Doug is wildly stabbing Mars when the frame freezes on his insanity filled gaze. In The Hills Have Eyes we don’t fade to black. No, we fade to blood red upon the realization our heroes, our nuclear family, have been completely broken in the face of a literal nuclear affected family. It’s the type of subversion Craven built his career off of. Despite resisting a return to the horror genre, Craven nonetheless went “balls to the wall” once he got behind the camera on Hills. The Hills Have Eyes is a wild, untamed film that has the power to stir the feral child within us all. “Juicy.”

Those who haven’t seen the film in a long time, I highly recommend the Arrow Video release from last year. The original 16mm camera negatives (shot on cameras borrowed from a California pornographer!) are presumed lost and what remains were 35mm prints. This leads to a fairly uneven transfer, but it’s likely the best the film will ever look. Plus, a little film grain and grime makes a movie like this all the better.

Editorials

‘Heathers’ – 1980s Satire Is Sharper Than Ever 35 Years Later

“When I was just a little girl I asked my mother, what will I be? Will I be pretty? Will I be rich? Here’s what she said to me: Qué será, será. Whatever will be, will be”

The opening of Michael Lehmann’s Heathers begins with a dreamy cover of a familiar song. Angelic voices ask a mother to predict the future only to be met with an infuriating response: “whatever will be, will be.” Her answer is most likely intended to present a life of limitless possibility, but as the introduction to a film devoid of competent parents, it feels like a noncommittal platitude. Heathers is filled with teenagers looking for guidance only to be let down by one adult after another. Gen Xers and elder millennials may have glamorized the outlandish fashion and creative slang while drooling over a smoking hot killer couple, but the violent film now packs an ominous punch. 35 years later, those who enjoyed Heathers in its original run may have more in common with the story’s parents than its teens. That’s right, Lehmann’s Heathers is now old enough to worry about its kids.

Veronica Sawyer (Winona Ryder) is the newest member of Westerberg High’s most popular clique. Heather Chandler (Kim Walker), sits atop this extreme social hierarchy ruling her minions and classmates alike with callous cruelty and massive shoulder pads. When Veronica begins dating a mysterious new student nicknamed J.D. (Christian Slater), they bond over hatred for her horrendous “friends.” After a vicious fight, a prank designed to knock Heather off her high horse goes terribly wrong and the icy mean girl winds up dead on her bedroom floor. Veronica and J.D. frantically stage a suicide, unwittingly making Heather more popular than ever. But who will step in to fill her patent leather shoes? With an ill-conceived plan to reset the social order, has Veronica created an even more dangerous monster?

Heathers debuted near the end of an era. John Hughes ruled ’80s teen cinema with instant classics like Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off while the Brat Pack dominated headlines with devil-may-care antics and sexy vibes. The decade also saw the rise of the slasher; a formulaic subgenre in which students are picked off one by one. Heathers combines these two trends in a biting satire that challenges the feel-good conclusions of Hughes and his ilk. Rather than a relatable loser who wins a date with the handsome jock or a loveable misfit who stands up to a soulless principal, Lehmann’s film exists in a world of extremes. The popular kids are vapid monsters, the geeks are barely human, the outcasts are psychopaths, and the adults are laughably incompetent. Veronica and a select few of her classmates feel like human beings, but the rest are outsized archetypes designed to push the teen comedy genre to its outer limits.

Mean girls have existed in fiction ever since Cinderella’s wicked stepsisters tried to steal her man, but modern iterations arguably date back to Rizzo (Stockard Channing, Grease) and Chris Hargenson (Nancy Allen, Carrie). It might destroy Heather Chandler to know that she isn’t the first, but this iconic mean girl may be the most extreme. She knows exactly what her classmates think of her and uses her power to make others suffer. She reminds Veronica, “They all want me as a friend or a fuck. I’m worshiped at Westerburg and I’m only a junior.” With an icy glare and barely concealed rage, she stomps the halls playing cruel pranks and demanding her friends submit to her will. We see a brief glimpse of humanity at a frat party when she’s coerced into a sexual act, but she immediately squanders this good will by promising to destroy Veronica at school on Monday. However, the film does not revolve around Heather’s redemption and it doesn’t revel in her ruination. Lehmann is more concerned with how Veronica uses her own popularity than the way she dispatches her best friend/enemy. In her book Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to Hate, Anna Bogutskaya describes Heather Chandler as an evolution in female characterization and it’s refreshing to see a woman play such an unapologetic villain.

Heather Chandler may die in the film’s first act, but her legacy can still be felt in both film and TV. Shannen Doherty would go on to specialize in catty characters both onscreen and off while Walker’s performance inspired the 2004 comedy Mean Girls (directed by Mark Waters, brother of Heathers screenwriter Daniel Waters). Early seasons of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Dawson’s Creek, Gossip Girl, and Pretty Little Liars all feature at least one glamorous bitch and mean girls can currently be seen battling on HBO’s Euphoria. Tina Fey’s Regina George (Rachel McAdams) sparked an important dialogue about female bullying and modern iterations add humanity to this contemptible character. With a rageful spit at her reflection in the mirror, Walker’s Heather hints at a deep well of pain beneath her unthinkable cruelty and we’ve been examining the motivations of her followers ever since.

But Heather Chandler is not the film’s major antagonist. While the blond junior roams the cafeteria insulting her classmates with an inane lunchtime poll, a true psychopath watches from the corner. J.D. lives with his construction magnate father and has spent his teenage years bouncing around from school to school. At first, Veronica is impressed with his frank morality and compassion for Heather’s victims, but this righteous altruism hides an inner darkness. The cafeteria scene ends with J.D. pulling a gun on two jocks and shooting them with blanks. This “prank” earns him a light suspension and a bad boy reputation, but it’s an uncomfortable precursor to our violent reality. He’s a prototypical school shooter obsessed with death, likely in response to his own traumatic past.

It’s impossible to talk about J.D. without mentioning the Columbine High School Massacre of 1999. Just over ten years later, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold would murder one teacher and twelve of their fellow classmates while failing to ignite a bomb that would decimate the building. Rumors swirled in the immediate aftermath about trench coat-wearing outcasts targeting popular students, but these theories have been largely disproven. However, uncomfortable parallels persist. Harris convinced a fellow student to join him in murder with tactics similar to the manipulation J.D. uses on Veronica. The cinematic character also fails in a plan to blow up the school and the stories of all three young men end in suicide. There is no evidence to suggest the Columbine killers were inspired by Slater’s performance but these similarities lend an uncomfortable element of prophecy to an already dark film.

In the past 35 years, we’ve become acutely aware of the adolescent potential for destruction. Unfortunately the adults of Heathers have their heads in the sand. We watch darkly humorous faculty meetings in which teachers discuss what they believe to be suicides and openly weigh the value of one student over the next. The only grownup who seems to care is Ms. Fleming (Penelope Milford) the guidance counselor and even she is woefully out of touch. Using dated hippie language, she stages an event where she pressures her students to hold hands and emote. Unfortunately she’s more interested in helping herself. Hoping to capitalize on her own empathy, she invites TV cameras to film her students grieving for their friends. She treats the decision to stay alive like she would the choice between colleges and asks Veronia about her own suspected suicide attempt with the same banality Heather brings to the lunchtime polls. This self-involved counselor is only interested in recording the answer, not actually connecting with the students she’s supposed to be guiding.

We also see a shocking lack of support from the film’s parents. J.D. and his father have fallen into a bizarre role-reversal with J.D. adopting the persona of a ’50s-era sitcom dad and his father that of an obedient son. Like Ms. Fleming’s performance, these practiced exchanges are meant to project the illusion of love while maintaining emotional distance between parent and child. Veronica’s own folks display similar detachment in vapid conversations repeated nearly word for word. They go through the motions of communication without actually saying anything of substance. When Veronica tries to talk about the deaths of her friends, her mother cuts her off with a cold, “you’ll live.” The next time Mrs. Sawyer (Jennifer Rhodes) sees her daughter, she’s hanging from the ceiling. Fortunately Veronica has staged this suicide to deceive J.D., but it’s only in perceived death that we see genuine empathy from her mother.

Another parent is not so lucky. J.D. has concocted an elaborate scene to murder jocks Kurt (Lance Fenton) and Ram (Patrick Labyorteaux) in the guise of a joint suicide between clandestined lovers and the world now believes his ruse. At the crowded funeral, a grief-stricken father stands next to a coffin wailing, “I love my dead gay son” while J.D. wonders from the pews if he would have this same compassion if his son was alive. It’s a brutal moment of truth in an outlandish film. Perhaps better parenting could have prevented Kurt from becoming the kind of bully J.D. would target. We now have a better understanding about the emotional support teenagers need, but the students in Heathers have been thrown to the wolves.

At the same funeral, Veronica sees a little girl crying in the front row. She not only witnesses the collateral damage she’s caused, but realizes that future generations are watching her behavior. She is showing young girls that social change is only possible through violence and others are copying this deadly trend. Despite the popular song Teenage Suicide (Don’t Do It!) by Big Fun, two other students attempt to take their own lives. Her teen angst has a growing body count and murdering her bullies has only turned them into martyrs.

Heathers delivers a somewhat happy ending by black comedy standards. After watching J.D. blow himself up, Veronica saunters back into school with a newfound freedom. She confronts Heather Duke (Doherty), the school’s reigning mean girl queen, and takes the symbolic red scrunchie out of her hair. Veronica declares herself the new sheriff in town and immediately begins her rule by making a friend. She approaches a severely bullied student and makes a date to watch videos on the night of the prom, using her popularity to lift someone else up. She’s learned on her own that taking out one Heather opens the door for someone else to step into the vacuum. The only way to combat toxic cruelty is to normalize acts of generosity. Rather than destroying her enemies, she will lead the school with kindness.

Heathers concludes with another rendition of “Que Sera, Sera.” In a more modern cover, a soloist delivers an informal answer hinting at a brighter future. We still don’t know what the future holds, but we don’t have to adhere to the social hierarchy we’ve inherited. We each have the power to decide what “will be” if we’re brave enough to separate ourselves from the popular crowd. The generation who watched Heathers as children are now raising their own teens and kids. One can only hope we’ve learned the lessons of this sharp satire. The future’s not ours to see, but if we guide our children with honesty and compassion, maybe we’ll raise a generation of Veronicas instead.

You must be logged in to post a comment.