Editorials

We Who Walk Here Walk Alone: Revisiting ‘The Haunting’ at 60

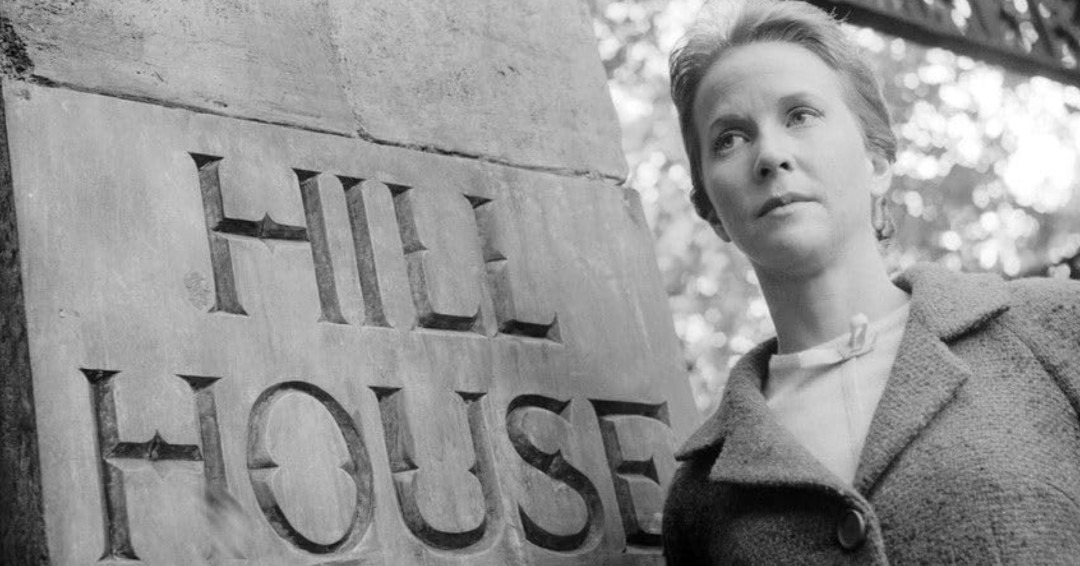

“Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within…and whatever walked there, walked alone.” – Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House (1959).

Of all the subgenres of horror, the haunted house story has provided the most opportunities for slow and subtle terror that creeps and crawls its way under the skin and into the psyche. The Old Dark House (1932), The Uninvited (1944), The Innocents (1961), Burnt Offerings (1976), and The Changeling (1980) stand among the best that not only the haunted house film, but all of horror have to offer. For many, the absolute pinnacle of these films is Robert Wise’s 1963 masterpiece of suggestive horror The Haunting. Based on the novel The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson, the film owes much to the influences of the past while still carving a way toward the future, is populated by rich and relatable characters, and is a deeply felt tragedy of the longing to matter in this big, lonely world.

Robert Wise came up through the ranks at RKO in the 1940s under the influence and presumably tutelage of its two greatest geniuses: Orson Welles and Val Lewton. The influence of these two mentors is evident onscreen in The Haunting in several ways. The film’s technique is in many ways Wellesian—deep focus, unique camera placement and movement, and the composition of the frame. As in the Orson Welles films Wise worked on as editor, Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), characters are set in different planes of depth within the frame, but all are in focus. They are then surrounded by grandiose set design, in the case of The Haunting, the rather baroque architecture of Hill House, which is not too far removed from the Amberson Mansion. Unfortunately, Wise had a great falling out with this first mentor as the studio forced him to re-edit the picture with a reshot ending without Welles’ involvement. Welles never forgave Wise for it and the two never spoke again. Still, the fingerprints of Welles remained as Wise grew as a filmmaker and his influence is very present in The Haunting.

Like the other great haunted house film of the 1960s, The Innocents, The Haunting is beautifully shot in that greatest and rarest of formats—black and white scope, or full widescreen; Twentieth Century Fox’s Cinemascope in the case of the former and Panavision in the latter. The techniques used are modern extensions of the kinds of pioneering work done by the builders of filmmaking language, and perfected by the masters of the 1930s and 40s. As expert as the technical aspects of the film are, they never detract from the story as is the case in the best Orson Welles films and those of Wise’s other great mentor Val Lewton, who gave him his first opportunity to direct a film with The Curse of the Cat People in 1944, another psychologically subtle film about a haunting.

Lewton’s influence is deeply felt in the way the film’s story is told. Lewton was far more interested in the psychological than the sensational. The horror films made between 1942 and 1946 at RKO by the Lewton unit are ambiguous, character-driven, and suggestive. The horror comes from what is not seen rather than from what is shown on screen. His philosophy was that what the audience imagines is far more horrifying than what the filmmaker can show. This makes Lewton’s films an interactive experience for the audience. Wise would often comment that people would say to him “you made the scariest movie I’ve ever seen, and you didn’t show anything.” This is the key to the continuing effectiveness of The Haunting. As with the best of the Lewton movies, it forces the active participation of the audience in that it provides just enough information and allows the imagination of each viewer to fill in the gaps.

This also allows for the psychological underpinnings of the story to work their way into the mind of each viewer and allows them to place themselves inside the situations on screen, or even behind the eyes of a character. For example, as Eleanor (Julie Harris) stares at the wall as she hears voices coming from the other side in one of the film’s most terrifying sequences, is it her or is it the audience that may or may not see a face forming in the shapes in the carvings on the wall? It happens so subtly that some may not even notice it upon first viewing. We are also allowed to ask questions like “is this all just in Eleanor’s mind?” before having the questions shifted when other evidence is presented. The film refuses to lay its cards on the table for as long as it possibly can, even in the iconic sequence in which the door bulges and flexes from some force behind it in the presence of believers and skeptics alike. That force remains unseen because Wise learned his lessons well from Lewton and perhaps H.P. Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe before him—what we imagine is far more horrifying than what we see.

One of the reasons why The Haunting works as well as it does is it is populated by characters who stand at different points on the spectrum of belief in the supernatural. Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson) believes in the validity of the spirit realm, but wants to prove it scientifically so even the greatest skeptic could not poke holes in his methods and theories. Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn) only believes in how much money he can make on Hill House after he inherits it and sells it off to the highest bidder. Theodora (Claire Bloom), known as Theo, is gifted with extra sensory perception but seems to think this could just be an uncanny ability to read people. In her youth, Eleanor had what Markway describes as “a poltergeist experience” in which “showers of stones fell on your house for three days.” But she brushes it off saying that her mother told her it was just the neighbors throwing rocks. More importantly, Eleanor desperately wants it all to be true, and feels that her inclusion in the Hill House experiment could be the one important thing she has been waiting for all her life. In the final act we are introduced to Markway’s wife Grace (Lois Maxwell) who feels that her husband has been wasting his life and destroying his academic reputation by chasing after ghosts.

These characters also have a great deal in common with those found in Lewton films. As in Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Seventh Victim, the lead characters in The Haunting are women, Eleanor and Theo, who are mirror images of each other. Eleanor, or Nell, is modest, retiring, something of a fragile flower desperate for belonging whose confidence has been chipped away by years of being the sole caregiver for her long-ailing mother. Theo is the opposite—confident, stylish, and in a way rather daring for 1963, openly gay. Same sex female attraction was often buried in the subtext of the Lewton films, specifically the three I mentioned above, but here, one does not need to dig very deep to find it as a key component of Theo. The focus of the film, however, is Eleanor. It is her story, and it is her tragedy.

The Haunting is a film of deep despair. Eleanor, so desperate to belong, so desperate to matter in this cold world, is swindled by a fraud. Not Markway or any of the companions she meets in Hill House, but the house itself. It convinces her that being within its walls is her destiny and her staying there for all time an inevitability. She clings to the line from a song sung in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, “journeys end in lovers meeting,” and she believes that Hill House is her lover, the one who will take her for who she is and not demand anything from her. But Hill House is not a lover as she imagines. It is a killer and a swallower of souls. Everything it does, it does for its own benefit. It is the epitome of “The Bad Place.” It does not give, it only takes.

When we are introduced to Nell, she believes there is something waiting for her that will solve all her problems. Instead, she becomes trapped by an obsession that ultimately destroys her. The film’s chilling final line proves that her loneliness only intensifies after Hill House takes what it wants—“we who walk here walk alone.” This is a change from the last line of the novel which repeats the famous opening that concludes “whatever walked there walked alone.” The change to “we who walk here” makes it all so much more personal. And savage. She is so desperate that her journey will end in lovers meeting, believing that Hill House will complete her that she becomes its willing prey. Instead of finding purpose and belonging, she will spend eternity trapped in solitude.

In various interviews Stephen King has conveyed a story about a phone call with Stanley Kubrick as he was adapting The Shining for what would become his 1980 film. To paraphrase the conversation, Kubrick said something like, “don’t you think that all ghost stories are inherently optimistic because they believe in an afterlife?” King thought about this and responded, “well, what about hell?” to which Kubrick responded, “I don’t believe in hell,” and hung up. This interchange somehow defines for me the conclusion of The Haunting, a film that is decidedly not optimistic about life after death. In the world of the film, an afterlife is proven, but not one of hope and joy, but of silence and abandonment. In the end, Nell seems to be trapped in a kind of hell. It is as if Dante’s ancient words should be inscribed upon the doorframes of Hill (Hell) House—“abandon hope all ye who enter here.” Hill House, not sane, stood for ninety years and may stand for ninety more. And those it takes it owns. And those it owns walk alone.

In Bride of Frankenstein, Dr. Pretorius, played by the inimitable Ernest Thesiger, raises his glass and proposes a toast to Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein—“to a new world of Gods and Monsters.” I invite you to join me in exploring this world, focusing on horror films from the dawn of the Universal Monster movies in 1931 to the collapse of the studio system and the rise of the new Hollywood rebels in the late 1960’s. With this period as our focus, and occasional ventures beyond, we will explore this magnificent world of classic horror. So, I raise my glass to you and invite you to join me in the toast.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.