Editorials

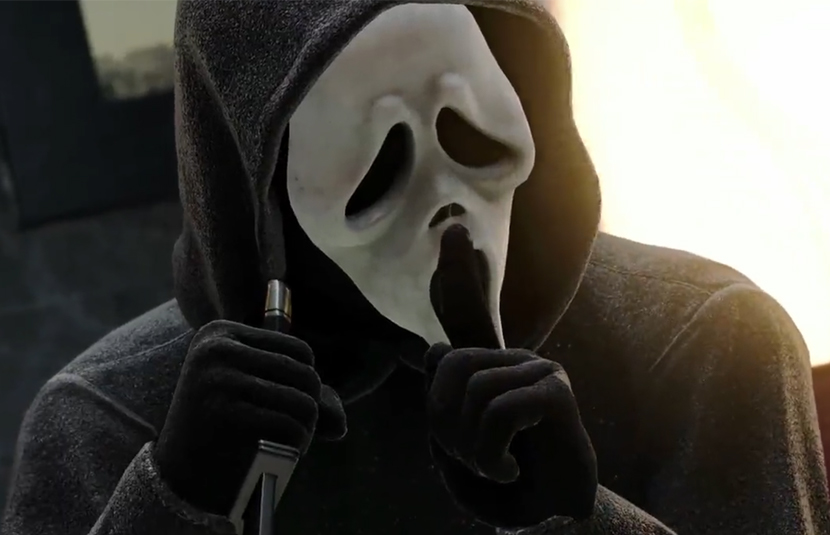

Scream in Your Hands: How To Evolve the Serial Killer Subgenre In Video Games

The release of the new Scream movie has me in the mood to play games where you’re trying to evade a slasher/serial killer. My personal favorites when it comes to this type of mayhem are that of Puppet Combo’s games; in gems like Babysitter Bloodbath and Murder House, you must run for your life as a mad killer tries to hunt you and butcher you. It’s very much in-tune with a slasher gem such as Scream. But though such games give me a rush, there is something more I long for from titles involving serial killers.

For a long time now, I’ve been craving a serial killer narrative with greater depth. Something that doesn’t rely on just thrills, but conveys a story that disturbs and moves. I want a game to get under the skin much like how David Fincher’s Seven does in its serial killer story – presenting a narrative with grim, moral exploration. So, I wonder: What would a game like that involve? When it comes to mechanics and narrative, what would it take to elevate the serial killer subgenre of gaming?

A Puzzle With All The Pieces Just Needing To Be Arranged

Outside that of the Scream and Friday the 13th inspired slasher games, other titles have touched upon more of the Seven-like serial killer narrative. Heavy Rain and the Condemned games are the first to come to mind, each making for decent efforts to provide intense, emotional stories (to varying quality respectively). Mechanically, each game offers a strong quality that is essential in building an effective detective game where one hunts down a killer.

Outside that of the Scream and Friday the 13th inspired slasher games, other titles have touched upon more of the Seven-like serial killer narrative. Heavy Rain and the Condemned games are the first to come to mind, each making for decent efforts to provide intense, emotional stories (to varying quality respectively). Mechanically, each game offers a strong quality that is essential in building an effective detective game where one hunts down a killer.

The obvious is that of investigation mechanics; the main means of interaction is the player moving about environments and striving to piece clues together. Much like we’ve seen in titles like the Batman Arkham games, this provides an immersive form of play if the player is to take on the role of a detective; this gets them into the dirt and grime of crime scenes, forcing them to be up close and personal when it comes to horrific violence. I’d love to see a game further expand upon this type of mechanic in greater detail; make us dig for evidence that leads us to our next destination; create an array of puzzles that revolve around discovering clues.

Another crucial element is creating a cinematic approach to gameplay exploration, much like that of Heavy Rain and Until Dawn. Providing investigative mechanics allow for players to engage with the world in an important manner – but besides that – I feel there needs to be a greater emphasis on plot outside of that, and not trying to layer on any other mechanics (i.e., combat). When you strip away fighting and only provide focus to exploration and investigation, one is left with a greater means to feel present in the story. There aren’t a bunch of enemies charging at them, no combos, or strategies to be mindful of, just the present in trying to find clues and absorb the atmosphere.

Though these games include elements of combat – to varying degrees – L.A. Noire and Judgment are titles that display a decent balance in juggling both essential qualities. However, both games lack any sort of horror element, making for fun detective games without a doubt, but offering little to make for unnerving experiences. So then, what would it take to narratively craft such a game?

Pain, Loss, And Anger – Feelings In Hunting Down A Killer

The general setup to any “detective hunts serial killer story” is relatively simple – it’s just that. That premise is the foundation to the plot. But to have such an experience make an impact on the player, it should involve some form of emotionality. While I’ve seen different games portray violence and emotional depth differently, what I don’t think works well are when these types of games get too “gamey” (i.e., relying on overt combat in trailing a killer), and opt for more play than plot. Such levels of engagement can create a distance and attitude of, “I’m going to get the killer, but these dead characters are just NPCs, so whatever.”

The general setup to any “detective hunts serial killer story” is relatively simple – it’s just that. That premise is the foundation to the plot. But to have such an experience make an impact on the player, it should involve some form of emotionality. While I’ve seen different games portray violence and emotional depth differently, what I don’t think works well are when these types of games get too “gamey” (i.e., relying on overt combat in trailing a killer), and opt for more play than plot. Such levels of engagement can create a distance and attitude of, “I’m going to get the killer, but these dead characters are just NPCs, so whatever.”

What would be a great countermeasure to such a mindset is creating a plot and gameplay experience where the player gets to take on multiple roles – such as that of the killer’s victims. Imagine a little side story where you are playing as a character you come to really like; you get to spend time in their shoes and see what their daily life is like. You develop a connection with them, only to find them in a situation where they are tortured and killed. This creates anger and a drive to push the player further into the story, making each action as the detective more important.

While completing objectives is crucial to help push a story forward, there needs to be just as much focus provided to the story. Imagine what it would be like to play a game where you felt super invested in catching a killer – like the game was really drawing upon you emotionally. If you’ve seen the film, think about Clarice from The Silence of the Lambs and how much her efforts make us root for her; think about how upsetting it feels to across the victims of Buffalo Bill. Now imagine yourself in the midst of such a story where everything depends on your actions – and you feel an emotional weight in all you do. This also applies to any detective character we may play as. Perhaps there is a side mission where the detective character is trying to celebrate a family member’s birthday, only for his thoughts to be clouded by horrible visions of what he has seen.

I also think it’s important for these types of games to pull us out of the heavier, more violent parts of the plot to (ironically), pull us deeper into the thick of things. These games could use moments of mundanity to emphasize the pain and suffering the killer has brought on. Think about the initial dinner scene in Seven where Brad Pitt, Morgan Freeman, and Gwyneth Paltrow are all sitting together; at this point in the film, Freeman, Pitt, and the audience have already seen some brutal stuff, but now we have a chill, friendly dinner gathering. The reason a moment like this works so well in the film is that – if the audience is to get constantly bombarded with violent imagery – there’s a chance they may grow distant from the characters and view the experience like torture porn. Having that dinner, having those quiet moments, allows us to connect and care more for characters, and that is a quality that serial killer video games could easily tap into.

There is so much room to create rich characters we feel for in these haunting dramas. There are whole layers of dark intrigue and gripping character dynamics that not only engage with the player on an entertainment basis, but also draw upon sympathy and empathy.

The Great Hunt To Come

I think when it comes to games that revolve around serial killers and slashers, too many keep things safe in presenting stories that only touch upon the aesthetics of gore and violence; like, “Look how crazy this killer is because he rips people’s faces off.” That’s cool and all, but I don’t want to just play around the typical beats of a serial killer narrative – I want to be on edge, uncomfortable, like being in the midst of a manhunt.

I think when it comes to games that revolve around serial killers and slashers, too many keep things safe in presenting stories that only touch upon the aesthetics of gore and violence; like, “Look how crazy this killer is because he rips people’s faces off.” That’s cool and all, but I don’t want to just play around the typical beats of a serial killer narrative – I want to be on edge, uncomfortable, like being in the midst of a manhunt.

A lot of horror games have seen tremendous growth over the years, and such growth is possible for the serial killer/slasher subgenre. There’s plenty of room and need for more action-driven horror flair, but I hope we see developers craft narratives that lean towards somber exploration and uncomfortable emotional impact. Journeys of hell, vengeance, and revenge where we as the player feel sincere anger towards the monster we are trailing.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.