Editorials

Bright Falls: How ‘Alan Wake 2’ Creates Environments Worth Exploring

The prospect of wandering around large, expansive game worlds used to fill me with excitement. Upon escaping the tutorial dungeon for the very first time in The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, I distinctly remember being overwhelmed by the sheer scale of that virtual playground rolling out before me, and the endless adventures that it tacitly promised. My awestruck 10-year-old brain couldn’t quite fathom that I was free to go in literally any direction and that, no matter which compass point I chose to follow, I was guaranteed to stumble across some memorable characters, tantalising locations or intriguing questlines.

As a kid who wasn’t yet able to buy their own games — and so usually had to wait until either Christmas or my birthday to get ahold of new releases — the idea of something having that kind of mileage seemed too good to be true. After all, I could make my sojourn in Cyrodill last for as long as I conceivably wanted and it was thus ideal for tiding me over during that agonising stretch between Decembers.

My sense of wanderlust carried over into some of Oblivion’s (similarly massive) contemporaries as well, like Grand Theft Auto 4, Mass Effect and fellow Bethesda stablemate; Fallout 3. Indeed, I really was a big proponent of these sandboxes for a while and, looking back, it’s crazy to think how many hours I’d willingly sink into even the genre’s weakest specimens (i.e. The Godfather II or the Mercenaries series).

How times have changed! Because, nowadays, there’s nothing that turns me off an open-world game more than discovering that it plans to occupy me for weeks on end with bottomless reams of content, and procedurally-generated fluff that only serves to bump up its “How Long to Beat” metrics.

I’m a grown adult with shit to do and a 9-5 job, so can’t possibly hope to fit several of these Homeric epics into my schedule month after month. At best I can maybe squeeze in a couple of them per year, but I’d much rather sample a wider range of titles than let a handful of unwieldy behemoths dominate my life anyway.

Alas, it feels like AAA releases are only moving further in this direction and getting more bloated as they each try to outdo one another, in what increasingly resembles a nuclear arms race. And I get it, I really do! Development budgets are spiralling out of control; there’s always pressure to offer more bang-for-your-buck than the other guy; and every publisher under the sun wants to produce the next “biggest game ever.”

It’s perfectly understandable then that all of these modern blockbusters are forced to have sprawling maps that are littered with collectibles, innumerable enemy outposts, and an inexhaustible supply of copy-pasted activities to keep you in their thrall. On paper, it’s a sensible business decision that maximises a title’s value for money and broadens its appeal.

Yet I don’t subscribe to this notion that bigger is automatically better. On the contrary, it’s often a red flag for me, as I assume the game in question is just being padded out to tick a corporate-mandated box. For instance, when the studio behind Dying Light 2 proudly boasted that their sequel would take up to 500 hours to beat (admittedly for a completionist run) I couldn’t have “noped” out of that proposition faster.

There are obviously some exceptions (Breath of the Wild, The Witcher 3 and Red Dead Redemption 2 spring to mind) but, for the most part, it feels like open worlds aren’t about giving you fulfilling things to do anymore, so much as they’re about maintaining constant player-engagement. Whether it’s fun or not.

It’s for this reason that I mainly gravitate towards more disciplined, linear experiences that I know will respect my time and make every last nanosecond count. It’s probably why I’m drawn to horror titles in particular, as they tend to be all killer, no filler.

Take 2023’s release slate for example! In the same timespan that it would take you to grind through roughly half of Starfield (most of which would be spent navigating its maddening U.I. and sprinting through barren expanses of nothingness), you’d be able to complete amazing gems like Dead Space, Resident Evil 4, The Outlast Trials, Amnesia: The Bunker, Dredge and Killer Frequency. The choice is a no-brainer in my opinion!

With that said, I was initially apprehensive when I learned that Alan Wake 2 was going to have quasi-open-world environments and even a few side-quests, because that idea seemed to fly in the face of what made its predecessor so damn addictive. Indeed, the original game was punchy and concise — broken up into digestible little “episodes” that were all too easy to binge. Every other minute would deliver an electrifying set piece, a quirky moment of surrealism or a head-spinning narrative revelation, but one thing it absolutely didn’t have was superfluous padding.

As such, I was concerned that some of this tight focus would be lost as the scope widened for its sequel, heralding that dreaded glut of open-world busywork. I didn’t want it to become just another drawn-out slog that outstays its welcome and artificially boosts its runtime with repetitive chores. That’s the exact opposite of what Alan Wake should be!

Fortunately, it turned out that I was worrying over nothing. In fact, Alan Wake 2’s optional distractions and detours ended up being some of my personal highlights from this survival horror masterpiece; enhancing the overall experience instead of diluting it.

A World Actually Worth Exploring

For a start, it helps that the environments here warrant touring in their own right and that would still be the case if there wasn’t even any gameplay incentive for doing so. It should go without saying, but one of the most important parts of creating an open world is making sure that it’s got enough personality to make you want to hang around in it and Bright Falls has that in spades.

A small town with a parochial outlook on just about everything, it’s fascinating to simply wander its streets and mingle with the eccentric locals. This is the kind of community where everybody knows their neighbours’ business and — bar recent supernatural occurrences — the most newsworthy event in the calendar is an annual deer-hunting festival. It feels intimate and lived-in, in a way that very few game words do.

After all, there’s a sense of artifice to the settings of, say, Forspoken or Ghost of Tsushima. Sure, they’re very grand and expansive (and at times, even beautiful) but the trade-off for this immense scale is that they’re also quite sterile. Everything in them seems to exist solely for the player. Villages are there to be liberated and nothing more, wildlife is either immediately hostile or else it’s part of some kind of transactional activity, infrastructure has apparently been built with your unique traversal abilities in mind, and passers-by are nought but set dressing. Obviously, this is the case with most games, but it comes across as especially phoney in those instances.

Conversely, you do buy into the illusion that the diegesis of Alan Wake continues to exist when you’re not around. I believe in Bright Falls as a real place. I believe in its quaint diners, its viscous mayoral race (with bizarre smear campaigns accusing one side of killing pets), its tourism trade based around elaborate bird feeders, its grizzly urban legends, and the folkloric history of Cauldron Lake. I also believe it’s such a humdrum municipality that the local disc jockey has to fill air time by ranking his favourite benches.

To me, this town is as well-realised and fleshed out as its clear inspirations in Twin Peaks or Derry, Maine. Like those fictional communities, it’s so oddly specific and rich in detail that it ends up feeling more alive than the populous streets of New York in Spider-Man or the supposedly bustling hub of New Atlantis in Starfield. I am an interloper on these streets, not the protagonist around whom everything else centres.

Because it all rings so true, I am compelled to explore and appreciate the weird little idiosyncrasies that Remedy took the time to feature. I want to pop by the jail and check in on those drunkards who keep getting locked up, even though there’s no practical reward for it whatsoever. Likewise, I am determined to find out what the deal is with that lonely old woman who keeps feeding the pigeons in the park and I’ll obsessively pour through every edition of the Bright Falls Chronicle — to read up on the human interest stories, and the competition to name a fabled lake monsters that looks suspiciously like a half-submerged log.

Meanwhile, over in the neighbouring town of Watery, I find myself drawn to the beverage-themed amusement park, Coffee World, and the small hut that’s used by old folks as both a makeshift sauna and a drinking spot. I sometimes just put the controller down for a good few minutes and listen to those OAPs humorously bicker about the noise levels and the availability of beer. It’s honestly a far more entertaining way of interacting with a game world than going through the tedious drudgery (popularised by Ubisoft) of clearing out multitudinous bandit camp or removing pesky objective markers from the map.

The Joy of Discovery

On that note, I love how organically you happen across these points of interest in Alan Wake 2. Your HUD isn’t cluttered with obnoxious icons, because Remedy isn’t terrified that you’ll miss something if they don’t spoon-feed it to you. Rather, they have complete faith in their product and trust that you’ll want to seek out these curiosities for yourself, so it doesn’t matter if you don’t catch every last detail on a first visit.

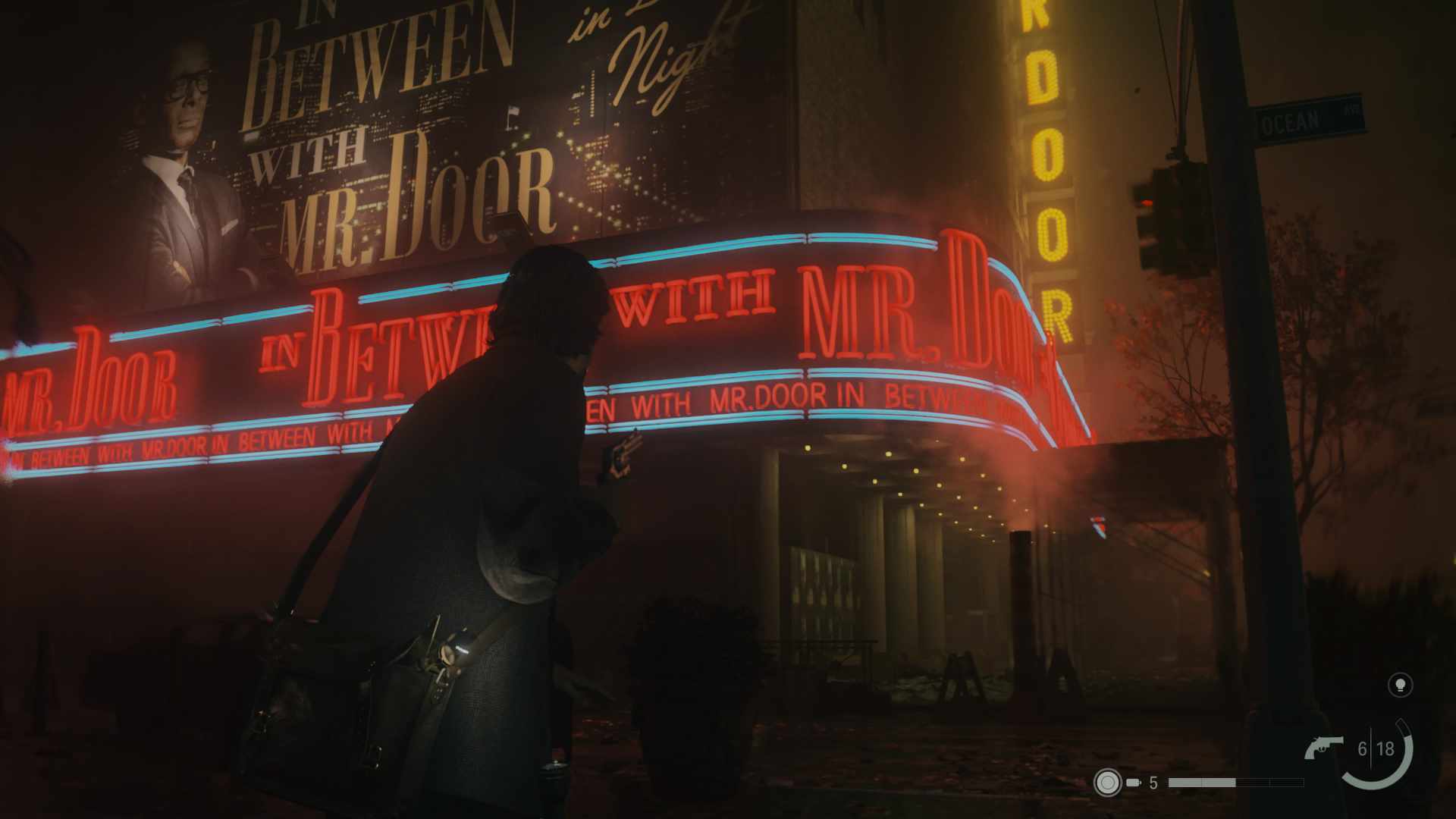

As such, there’s a real thrill of discovery whenever you unearth something cool, be it a neat reference to the Federal Bureau of Control or one of those hilariously awkward Koskela brother commercials. Similarly, when traversing the Dark Place you might spot a bit of graffiti that slyly nods towards events from the first game or unpack the lore behind a haunted hotel that bears more than a passing resemblance to the Overlook. These are finds that you came across entirely on your own and it’s all the more rewarding for that. In that sense, it reminded me a lot of this year’s equally brilliant Dredge, which also eschewed the conventional wisdom of open-world design in favour of a more hands-off approach.

I love when games encourage you to stray from the beaten path and go hunting for adventure in this way, as opposed to handing it all to you on a silver platter. It’s why titles like Elden Ring or Tears of the Kingdom keep people coming back for more, just in case they’ve missed something compelling.

That being said, Alan Wake 2 does have a pretty useful map system that can help you get your bearings in Bright Falls (as well as in the far less navigable Dark Place). Smartly taking a cue from the Silent Hill franchise, your atlas here will be freshly printed and squeaky clean when you first pick it up, only showing what you’d expect to see in a standard tourist leaflet or city ordinance document. Yet as you explore deeper, Saga/ Alan will begin to scribble on their respective maps, taking note of any recognisable landmarks they see, as well as geographical obstructions, locked doors, unfinished puzzles, and so on.

These handy jottings will then allow you to orient yourself in levels when you eventually backtrack to them, or go looking for any outstanding collectibles, in a way that feels truly immersive. It’s like you’re a proper detective figuring things out, instead of someone who is just blindly following waypoints that have been gifted to them by an omniscient developer. Not only that, but the mechanic pushes you to actively seek out any blank spots on your map, as those will remain a complete mystery until you do and there’s something so intensely fulfilling about watching the empty spaces get filled in.

All Killer, No Filler

Of course, it’s all and well good having a map that’s satisfying to parse, but it obviously needs to lead to valuable treasures. So to speak.

Fortunately, Alan Wake 2 has only the coolest shit to find. There are no obligatory radio towers to climb here, no recycled enemy outposts to wipe out (in fact, Taken encounters are refreshingly scarce, making them more of an event when they do occur) and no meaningless collectibles. Everything is substantive and has a purpose.

As Saga, you’ll be on the lookout for mind palace clues and manuscript pages that give you a deeper insight into the narrative, while Pat Maine’s radio broadcasts regale you with a fascinating tale of a presumed-dead jerky magnate. When it comes to loot, you can pillage caches that contain the type of supplies you always need in survival horror and even the odd firearm. Said weapons can then be upgraded with the resources you scavenge from lunchboxes dotted around Bright Falls (which themselves have their own unique backstory) and there are also some fun riddles to solve that allow you to reshape your surroundings by effectively playing with dolls.

On the Alan side of things, there are echoes of the past —featuring some dazzling blends of live-action and CG footage — Alex Casey easter eggs —that are bound to delight fans of a certain other Remedy franchise — and Words of Power upgrades that will test the limits of your observational skills. Not to mention, you can always experiment with Alan’s writerly talents to see just how malleable the Dark Place really is, unlocking shortcuts and triggering new events.

The point is that all of these activities are enjoyable in their own right and yield fruitful rewards. Ticking them off doesn’t feel like an obligation then, but rather something that you are driven to do. And that’s rarer than you might think nowadays.

With all of that said, hopefully, other developers will take notes from games like Alan Wake 2 when designing their open worlds in the future. Its tighter focus, emphasis on quality over quantity and keen understanding of what makes exploration fun to begin made this a much-needed breath of fresh air.

Editorials

What’s Wrong with My Baby!? Larry Cohen’s ‘It’s Alive’ at 50

Soon after the New Hollywood generation took over the entertainment industry, they started having children. And more than any filmmakers that came before—they were terrified. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Eraserhead (1977), The Brood (1979), The Shining (1980), Possession (1981), and many others all deal, at least in part, with the fears of becoming or being a parent. What if my child turns out to be a monster? is corrupted by some evil force? or turns out to be the fucking Antichrist? What if I screw them up somehow, or can’t help them, or even go insane and try to kill them? Horror has always been at its best when exploring relatable fears through extreme circumstances. A prime example of this is Larry Cohen’s 1974 monster-baby movie It’s Alive, which explores the not only the rollercoaster of emotions that any parent experiences when confronted with the difficulties of raising a child, but long-standing questions of who or what is at fault when something goes horribly wrong.

Cohen begins making his underlying points early in the film as Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) discusses the state of the world with a group of expectant fathers in a hospital waiting room. They discuss the “overabundance of lead” in foods and the environment, smog, and pesticides that only serve to produce roaches that are “bigger, stronger, and harder to kill.” Frank comments that this is “quite a world to bring a kid into.” This has long been a discussion point among people when trying to decide whether to have kids or not. I’ve had many conversations with friends who have said they feel it’s irresponsible to bring children into such a violent, broken, and dangerous world, and I certainly don’t begrudge them this. My wife and I did decide to have children but that doesn’t mean that it’s been easy.

Immediately following this scene comes It’s Alive’s most famous sequence in which Frank’s wife Lenore (Sharon Farrell) is the only person left alive in her delivery room, the doctors clawed and bitten to death by her mutant baby, which has escaped. “What does my baby look like!? What’s wrong with my baby!?” she screams as nurses wheel her frantically into a recovery room. The evening that had begun with such joy and excitement at the birth of their second child turned into a nightmare. This is tough for me to write, but on some level, I can relate to this whiplash of emotion. When my second child was born, they came about five weeks early. I’ll use the pronouns “they/them” for privacy reasons when referring to my kids. Our oldest was still very young and went to stay with my parents and we sped off to the hospital where my wife was taken into an operating room for an emergency c-section. I was able to carry our newborn into the NICU (natal intensive care unit) where I was assured that this was routine for all premature births. The nurses assured me there was nothing to worry about and the baby looked big and healthy. I headed to where my wife was taken to recover to grab a few winks assuming that everything was fine. Well, when I awoke, I headed back over to the NICU to find that my child was not where I left them. The nurse found me and told me that the baby’s lungs were underdeveloped, and they had to put them in a special room connected to oxygen tubes and wires to monitor their vitals.

It’s difficult to express the fear that overwhelmed me in those moments. Everything turned out okay, but it took a while and I’m convinced to this day that their anxiety struggles spring from these first weeks of life. As our children grew, we learned that two of the three were on the spectrum and that anxiety, depression, ADHD, and OCD were also playing a part in their lives. Parents, at least speaking for myself, can’t help but blame themselves for the struggles their children face. The “if only” questions creep in and easily overcome the voices that assure us that it really has nothing to do with us. In the film, Lenore says, “maybe it’s all the pills I’ve been taking that brought this on.” Frank muses aloud about how he used to think that Frankenstein was the monster, but when he got older realized he was the one that made the monster. The aptly named Frank is wondering if his baby’s mutation is his fault, if he created the monster that is terrorizing Los Angeles. I have made plenty of “if only” statements about myself over the years. “If only I hadn’t had to work so much, if only I had been around more when they were little.” Mothers may ask themselves, “did I have a drink, too much coffee, or a cigarette before I knew I was pregnant? Was I too stressed out during the pregnancy?” In other words, most parents can’t help but wonder if it’s all their fault.

At one point in the film, Frank goes to the elementary school where his baby has been sighted and is escorted through the halls by police. He overhears someone comment about “screwed up genes,” which brings about age-old questions of nature vs. nurture. Despite the voices around him from doctors and detectives that say, “we know this isn’t your fault,” Frank can’t help but think it is, and that the people who try to tell him it isn’t really think it’s his fault too. There is no doubt that there is a hereditary element to the kinds of mental illness struggles that my children and I deal with. But, and it’s a bit but, good parenting goes a long way in helping children deal with these struggles. Kids need to know they’re not alone, a good parent can provide that, perhaps especially parents that can relate to the same kinds of struggles. The question of nature vs. nurture will likely never be entirely answered but I think there’s more than a good chance that “both/and” is the case. Around the midpoint of the film, Frank agrees to disown the child and sign it over for medical experimentation if caught or killed. Lenore and the older son Chris (Daniel Holzman) seek to nurture and teach the baby, feeling that it is not a monster, but a member of the family.

It’s Alive takes these ideas to an even greater degree in the fact that the Davis Baby really is a monster, a mutant with claws and fangs that murders and eats people. The late ’60s and early ’70s also saw the rise in mass murderers and serial killers which heightened the nature vs. nurture debate. Obviously, these people were not literal monsters but human beings that came from human parents, but something had gone horribly wrong. Often the upbringing of these killers clearly led in part to their antisocial behavior, but this isn’t always the case. It’s Alive asks “what if a ‘monster’ comes from a good home?” In this case is it society, environmental factors, or is it the lead, smog, and pesticides? It is almost impossible to know, but the ending of the film underscores an uncomfortable truth—even monsters have parents.

As the film enters its third act, Frank joins the hunt for his child through the Los Angeles sewers and into the L.A. River. He is armed with a rifle and ready to kill on sight, having divorced himself from any relationship to the child. Then Frank finds his baby crying in the sewers and his fatherly instincts take over. With tears in his eyes, he speaks words of comfort and wraps his son in his coat. He holds him close, pats and rocks him, and whispers that everything is going to be okay. People often wonder how the parents of those who perform heinous acts can sit in court, shed tears, and defend them. I think it’s a complex issue. I’m sure that these parents know that their child has done something evil, but that doesn’t change the fact that they are still their baby. Your child is a piece of yourself formed into a whole new human being. Disowning them would be like cutting off a limb, no matter what they may have done. It doesn’t erase an evil act, far from it, but I can understand the pain of a parent in that situation. I think It’s Alive does an exceptional job placing its audience in that situation.

Despite the serious issues and ideas being examined in the film, It’s Alive is far from a dour affair. At heart, it is still a monster movie and filled with a sense of fun and a great deal of pitch-black humor. In one of its more memorable moments, a milkman is sucked into the rear compartment of his truck as red blood mingles with the white milk from smashed bottles leaking out the back of the truck and streaming down the street. Just after Frank agrees to join the hunt for his baby, the film cuts to the back of an ice cream truck with the words “STOP CHILDREN” emblazoned on it. It’s a movie filled with great kills, a mutant baby—created by make-up effects master Rick Baker early in his career, and plenty of action—and all in a PG rated movie! I’m telling you, the ’70s were wild. It just also happens to have some thoughtful ideas behind it as well.

Which was Larry Cohen’s specialty. Cohen made all kinds of movies, but his most enduring have been his horror films and all of them tackle the social issues and fears of the time they were made. God Told Me To (1976), Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), and The Stuff (1985) are all great examples of his socially aware, low-budget, exploitation filmmaking with a brain and It’s Alive certainly fits right in with that group. Cohen would go on to write and direct two sequels, It Lives Again (aka It’s Alive 2) in 1978 and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive in 1987 and is credited as a co-writer on the 2008 remake. All these films explore the ideas of parental responsibility in light of the various concerns of the times they were made including abortion rights and AIDS.

Fifty years after It’s Alive was initially released, it has only become more relevant in the ensuing years. Fears surrounding parenthood have been with us since the beginning of time but as the years pass the reasons for these fears only seem to become more and more profound. In today’s world the conversation of the fathers in the waiting room could be expanded to hormones and genetic modifications in food, terrorism, climate change, school and other mass shootings, and other threats that were unknown or at least less of a concern fifty years ago. Perhaps the fearmongering conspiracy theories about chemtrails and vaccines would be mentioned as well, though in a more satirical fashion, as fears some expectant parents encounter while endlessly doomscrolling Facebook or Twitter. Speaking for myself, despite the struggles, the fears, and the sadness that sometimes comes with having children, it’s been worth it. The joys ultimately outweigh all of that, but I understand the terror too. Becoming a parent is no easy choice, nor should it be. But as I look back, I can say that I’m glad we made the choice we did.

I wonder if Frank and Lenore can say the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.