Editorials

The Fragility of Human Existence: A 10-Year Retrospective on Duncan Jones’ Sci-fi Film ‘Moon’

“How real are our emotions, anyway? How real are we? Someday I will die. This laptop I’m using is patient and can wait.”

In his official review for the Duncan Jones science-fiction drama, Moon, critic Roger Ebert mentioned that his interpretation of the film’s story and themes reflected on the idea of human life potentially being worthless and expendable as technology continues to advance. The quote used above signified Ebert’s own questions about the worth of human lives and emotions, boldly stating that in spite of our eventual deaths, the objects we own will not miss us and will continue to live a different life under potential new owners.

It’s depressing to believe that the end of our lives will signal the end of our existence as a whole. Of course, we don’t know what will happen and while some of us believe that there is a whole other world waiting for us on the other side, it’s ultimately fruitless to accurately speculate on life after death; but Ebert’s eye-opening review of Moon looks at death from the perspective of the outside. Sure, we may not know what happens when WE die, but the thing that’s for certain is that the living world will move on, in one way or another, slowly leaving the memory of us to fade away.

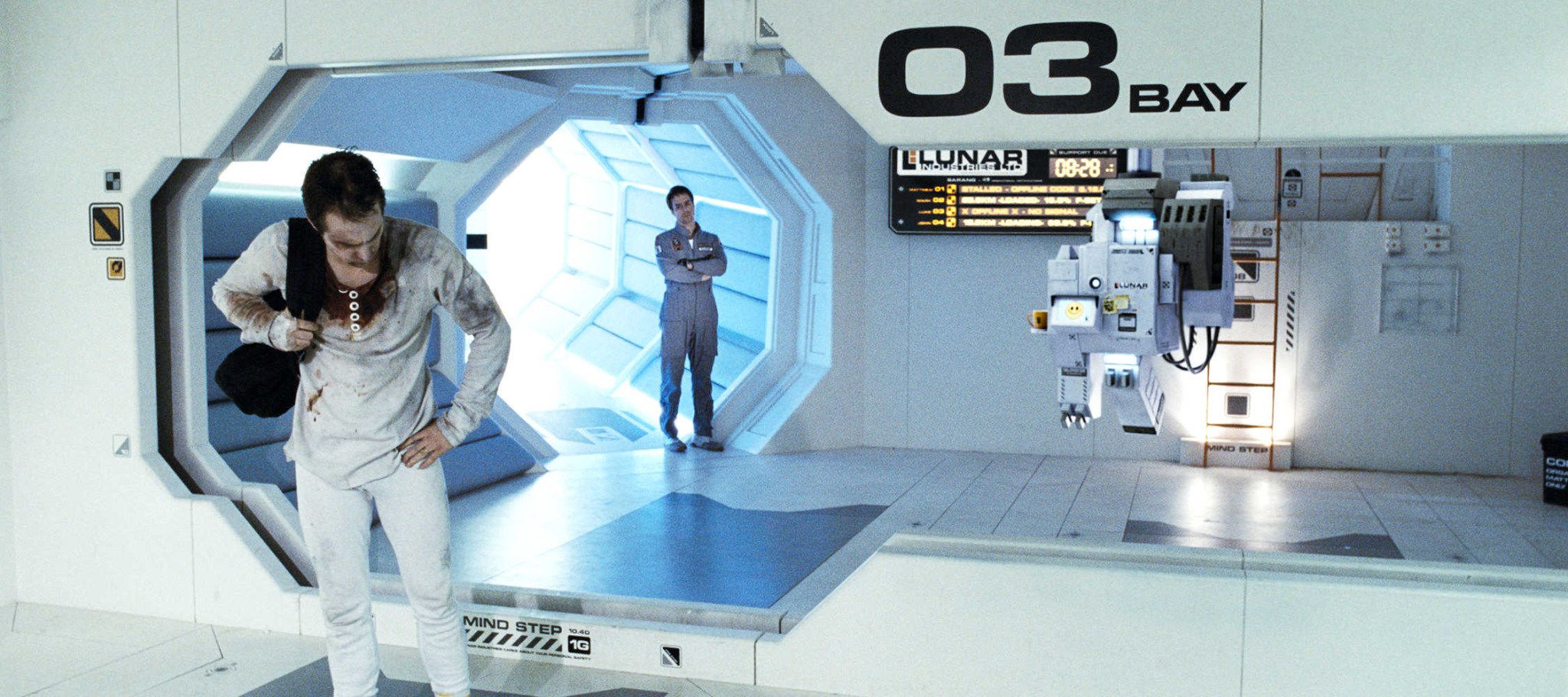

This conflict of existence is something that the main protagonist of Moon, Sam Bell, faces head-on in the most unexpected way, uncovering an entire conspiracy revolving around the manipulation of human existence and memories. This is especially jarring when the start of the film shows him casually going about his work on the moon, where he is stationed for three years to overlook a mining station that mines for helium-3, a rich alternative to oil, for the wealthy and thriving Lunar Industries.

As Sam nears the end of his three-year stay, he begins to see strange visions on the moon, leading him to crash his rover during a drive on the moon. He wakes up with seemingly no memory of the accident, but when he goes to see the crashed rover, he finds…himself, stuck in the same position he was when he crashed the rover. From here, we have a trippy sci-fi clone story as the two Sams (performed with gusto by the amazing Sam Rockwell) try to figure out what is happening to them and why there are two of them in the first place.

Moon didn’t exactly light up the world when it was first released back in 2009. The critical reception was high, but audiences didn’t seem to jive with the story as much; the film made just under $10 million at the box office with no major awards love outside of a BAFTA nomination for Best British Film. There are tons of movies with this kind of reputation: a critical darling that fails to appeal to a wide audience resulting in a lackluster theater performance. Not quite cult films, but films that tend to have a longer life on streaming, as we call it nowadays.

But in some way, despite the low returns, Moon has continued to stay relevant in the conversation of science fiction films, all while Damien Chazelle’s First Man is hardly even mentioned anymore, despite only coming out late last year. Moon has etched out a niche for itself in the world of science fiction by combining a space isolation story with themes akin to those in the Blade Runner films, crafting a wholly unique space experience from more conventional space thrillers like Gravity, Sunshine, or Armageddon.

However, more than its general quality of filmmaking, the evolution of technology has prompted Moon to carve out a spot in relevancy for space films. The film has a prime focus on the use of automated labor, gradually depending less on the use of human workers to the point where the space station in the film requires only one actual human (well, not really, but at a time yeah) to supervise. Artificial intelligence does a majority of the heavy lifting here, from maintaining contact with Earth to creating new solutions should a problem with Sam arise during the tenure.

Spoilers ahead for Moon.

Technology is also responsible for the hibernation of the Sam Bell clones, keeping them preserved for whenever the current Sam “model” breaks down, constantly having a backup for the next three years as Lunar Industries saves money on training astronauts as replacements and the cost of going to the moon. Clones are born and programmed to die on the moon, living out their entire lives believing that they are the original Sam Bell. It’s a human experiment project with advanced cloning technology providing every needed resource.

Blade Runner’s influence bears heavy on Moon’s subject matter and themes. As humanity continues to assist in the evolution of more advanced technology, the idea of creating “human” clones to offset the workload from “real” humans back home is something pulled straight out of a Philip K. Dick novel. Exactly how far will we go in this endeavor and at what point do we consider the clones to be beings with human rights? They operate just like humans, complete with the same mannerisms, memories, and emotions as one, so where’s the line drawn?

Moon explores this through the gradual decay of the older Sam clone, whose time is drawing closer before his manufactured time is up. The clone, like the others, contains the same level of excitement for his time ending as anybody would, with his implanted memories leading him to believe that he’ll be coming home to his wife and daughter soon. But as this reality is shattered, Sam grapples with his own humanity, which was technically created by others, but is something that is ultimately unique to him in the end.

Though this situation is obviously a tiny bit exaggerated for movie purposes, cloning is a very real area of scientific study that has garnered significant controversy for its ethical nature and the alleged God complex that comes with creating a human life in such fashion. It is banned in about 70 countries right now as I write this, but the argument for using cloning and stem cell research to develop cures and new methods for creation is still going strong today and will probably continue to do so in the future.

Human/animal cloning was certainly being looked at in 2009 when Moon was released, but in the 10 years since, cloning has evolved to the point where, in 2018, two live clones of primates were successfully created through the use of somatic cell nuclear transfer. It took some time, but clones were created nonetheless, further bringing the world of science closer to the cloning practices done in Moon.

The cloning of today is already an evolved area of science, but how long before cloning goes further? Will clones be made from other clones? Will entire identities be constructed to fit the desires of the creator(s)? How long before the lives we live are no longer our own? A paranoid point to consider is just how obsolete “original” humans may be in the future, just as they seem to be moving towards in Moon. Humans still have a function of sorts, but the clones themselves are gradually carrying the workloads on their backs, along with A.I. machines to help with the physical cloning process.

In the 10 years since Moon released, American cinema has begun to slowly integrate the idea of human cloning and manufactured existence into their narratives, prime examples being this year’s Us and I Am Mother, as well as Annihilation and Blade Runner 2049. The latter, in particular, bears an eerie resemblance to Moon not just in the concept of creating humanoid beings, but implanting memories for the purpose of the recipient taking them in as their own. Agent K’s memories are implanted from an existing human, crafting an identity suited to the purposes of his creators, much like Sam Bell in Moon.

Both films also end in similar places. For BR 2049, K abandons the notion that he is without purpose and selflessly sacrifices himself for Rick Deckard’s survival, using his final moments to go against the wishes of his creators and create his own ending. He goes on HIS terms. Same goes for the older Sam Bell clone, who convinces younger Sam to hide in one of the vessels used to send the helium back to Earth, while older Sam covers up his escape and dies knowing that his younger clone will be able to tell their story on Earth.

In these movies, identity is created, but never consistently maintained. As soon as the clones/androids gain knowledge of their true purpose, it is never their intentions to follow through with their orders. Their identities were crafted from scratch, but the end of their stories leads them down the path they choose from their own free will. Even if they die, their deaths are seen as sighs of relief, as they are free to go out how they please.

Back to Roger Ebert’s review, the idea of our existence is questioned by Ebert and he seems to take the film’s exploration of humanity into serious consideration. How much of our lives are indeed OUR lives? Can we do anything to change it? Moon doesn’t skimp away from scaring the audience into questioning their own states of being, but its ending suggests that our lives may indeed be fulfilled through our own individual choices. We may be created for a purpose, but it is ultimately up to us to decide how we may live our lives.

To quote Rocketman, “You gotta kill the person you were born to be in order to become the person you wanna be.” It may seem a little ill-fitting to quote a musical biopic in an analysis of a science-fiction horror-drama, but it’s this philosophy that Moon runs with at film’s end. The Sam Bell clone may have been created for labor, but now it is up to him to handle his own situation as he comes back to Earth. He is now living not as a clone of Sam Bell, but as a person who just so happens to look like another person named Sam on Earth. His existence is just getting started.

For its tenth anniversary, Moon has just been added to the ever-growing Shudder library, where you can watch the film and judge its themes for yourself.

Editorials

Silly, Self-Aware ‘Amityville Christmas Vacation’ Is a Welcome Change of Pace [The Amityville IP]

Twice a month Joe Lipsett will dissect a new Amityville Horror film to explore how the “franchise” has evolved in increasingly ludicrous directions. This is “The Amityville IP.”

After a number of bloated runtimes and technically inept entries, it’s something of a relief to watch Amityville Christmas Vacation (2022). The 55-minute film doesn’t even try to hit feature length, which is a wise decision for a film with a slight, but enjoyable premise.

The amusingly self-aware comedy is written and directed by Steve Rudzinski, who also stars as protagonist Wally Griswold. The premise is simple: a newspaper article celebrating the hero cop catches the attention of B’n’B owner Samantha (Marci Leigh), who lures Wally to Amityville under the false claim that he’s won a free Christmas stay.

Naturally it turns out that the house is haunted by a vengeful ghost named Jessica D’Angelo (Aleen Isley), but instead of murdering him like the other guests, Jessica winds up falling in love with him.

Several other recent Amityville films, including Amityville Cop and Amityville in Space, have leaned into comedy, albeit to varying degrees of success. Amityville Christmas Vacation is arguably the most successful because, despite its hit/miss joke ratio, at least the film acknowledges its inherent silliness and never takes itself seriously.

In this capacity, the film is more comedy than horror (the closest comparison is probably Amityville Vibrator, which blended hard-core erotica with references to other titles in the “series”). The jokes here are enjoyably varied: Wally glibly acknowledges his racism and excessive use of force in a way that reflects the real world culture shift around criticisms of police work; the last names of the lovers, as well the title of the film, are obvious homages to the National Lampoon’s holiday film; and the narrative embodies the usual festive tropes of Hallmark and Lifetime Christmas movies.

This self-awareness buys the film a certain amount of goodwill, which is vital considering Rudzinski’s clear budgetary limitations. Jessica’s ghost make-up is pretty basic, the action is practically non-existent, and the whole film essentially takes place in a single location. These elements are forgivable, though audiences whose funny bone isn’t tickled will find the basic narrative, low stakes, and amateur acting too glaring to overlook. It must be acknowledged that in spite of its brief runtime, there’s still an undeniable feeling of padding in certain dialogue exchanges and sequences.

Despite this, there’s plenty to like about Amityville Christmas Vacation.

Rudzinski is the clear stand-out here. Wally is a goof: he’s incredibly slow on the uptake and obsessed with his cat Whiskers. The early portions of the film lean on Wally’s inherent likeability and Rudzinski shares an easy charm with co-star Isley, although her performance is a bit more one-note (Jessica is mostly confused by the idiot who has wandered into her midst).

Falling somewhere in the middle are Ben Dietels as Rick (Ben Dietels), Wally’s pathetic co-worker who has invented a family to spend the holidays with, and Zelda (Autumn Ivy), the supernatural case worker that Jessica Zooms with for advice on how to negotiate her newfound situation.

The other actors are less successful, particularly Garrett Hunter as ghost hunter Creighton Spool (Scott Lewis), as well as Samantha, the home owner. Leigh, in particular, barely makes an impression and there’s absolutely no bite in her jealous threats in the last act.

Like most comedies, audience mileage will vary depending on their tolerance for low-brow jokes. If the idea of Wally chastising and giving himself a pep talk out loud in front of Jessica isn’t funny, Amityville Christmas Vacation likely isn’t for you. As it stands, the film’s success rate is approximately 50/50: for every amusing joke, there’s another one that misses the mark.

Despite this – or perhaps because of the film’s proximity to the recent glut of terrible entries – Amityville Christmas Vacation is a welcome breath of fresh air. It’s not a great film, but it is often amusing and silly. There’s something to be said for keeping things simple and executing them reasonably well.

That’s a lesson that other indie Amityville filmmakers could stand to learn.

The Amityville IP Awards go to…

- Recurring Gag: The film mines plenty of jokes from characters saying the quiet part (out) loud, including Samantha’s delivery of “They’re always the people I hate” when Wally asks how he won a contest he didn’t enter.

- Holiday Horror: There’s a brief reference that Jessica died in an “icicle accident,” which plays like a perfect blend between a horror film and a Hallmark film.

- Best Line: After Jessica jokes about Wally’s love of all things cats to Zelda, calling him the “cat’s meow,” the case worker’s deadpan delivery of “Yeah, that sounds like an inside joke” is delightful.

- Christmas Wish: In case you were wondering, yes, Santa Claus (Joshua Antoon) does show up for the film’s final joke, though it’s arguably not great.

- Chainsaw Award: This film won Fangoria’s ‘Best Amityville’ Chainsaw award in 2023, which makes sense given how unique it is compared to many other titles released in 2022. This also means that the film is probably the best entry we’ll discuss for some time, so…yay?

- ICYMI: This editorial series was recently included in a profile in the The New York Times, another sign that the Amityville “franchise” will never truly die.

Next time: we’re hitting the holidays in the wrong order with a look at November 2022’s Amityville Thanksgiving, which hails from the same creative team as Amityville Karen <gulp>

You must be logged in to post a comment.