Editorials

Field of Screams – ‘Night of the Scarecrow’ Is an Unsung ’90s Supernatural Slasher

Despite the decline in theatrical horror releases during the 1990s, the direct-to-video side of the genre was still thriving. So much so that something like Jeff Burr’s Night of the Scarecrow understandably slipped through the cracks after its unnoticed home-video premiere in ‘96. Even aficionados of this regularly dismissed decade of horror might not be aware of the movie’s existence. Nevertheless, longtime fans still consider this to be one of the more notable offerings of scarecrow horror.

It’s not hard to figure out why Night of the Scarecrow got so lost in the shuffle of ‘90s DTV horror. Jeff Burr claimed only around 12,000 units were shipped back in the bygone days of video shops. Yet, if you came across this movie’s alluring box art in the horror aisle, you couldn’t be blamed for wanting to take a closer look. The alternative artwork — the titular, sickle-wielding villain hangs ominously from his field post — looks too lifeless when placed next to the more menacing and confrontational illustration used for other releases and merchandise, including a single-issue comic book. However, both of these key images strike a nerve about people’s perception of scarecrows. Their humanoid forms, dressed in hand-me-downs and left to waste in open solitude, could be mistaken for corpses.

Supernatural slashers experienced a small and brief surge of popularity in the early half of the ‘90s before Scream brought mortal killers back into style. Night of the Scarecrow seems trendy, but the story originated in 1990. Originally just called Scarecrow, the project was a blatant attempt to capitalize on the Nightmare on Elm Street series. The plans ultimately fell through once the studio, Corsair, went under. Producers Barry Bernardi and Steven White then picked up Reed Steiner and Dan Mazur’s script a few years later. Once Scarecrow landed in new hands, though, the previously projected budget of $5-6 million was reduced to $1.5-2 million. The final product was, of course, sent straight to video, courtesy of Republic Pictures.

Image: Stephen Root’s character is confronted by The Scarecrow.

Evil manifests below the ground in Night of the Scarecrow, yet this B-movie hardly breaks new ground. It’s Burr’s know-how with these kinds of stock horror movies that makes the whole thing come together. After all, the late filmmaker was familiar with ancient evils wreaking havoc in the present; he had just finished the first sequel to Pumpkinhead prior to signing on to this movie. Although truth be told, Scarecrow surpasses Pumpkinhead II: Blood Wings in most technical respects. Director of photography Thomas L. Callaway (Slumber Party Massacre II, Demon Wind) had a lot to do with the unexpectedly gothic look of this production. That’s not to say every visual element here is perfect; the optical effects, according to Burr himself, look “dreadful.” One particular moment where the villain suddenly morphs out of a random haystack (and says “hey there” to John Hawkes‘ character) is always a source of amusement.

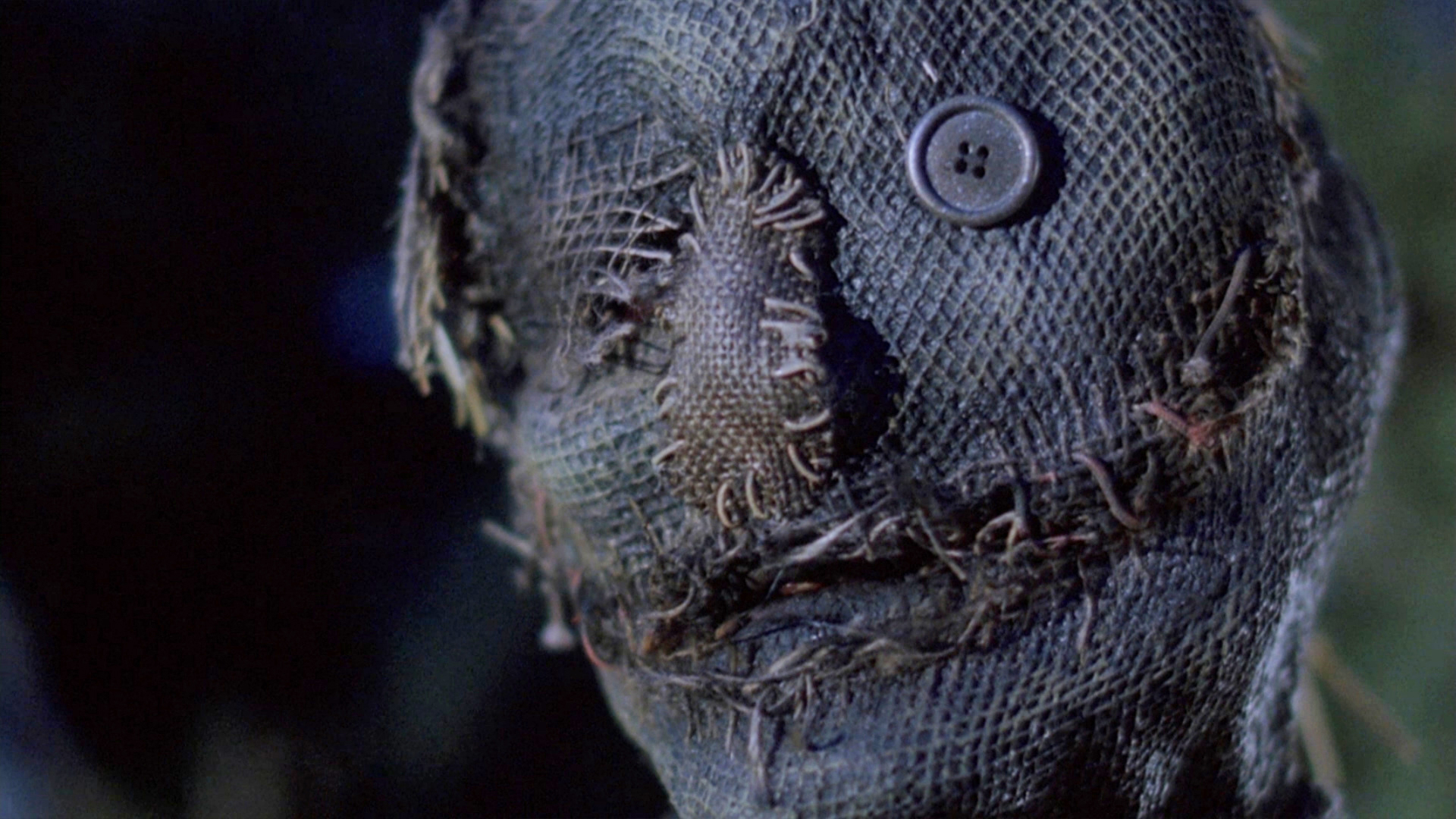

Scarecrows don’t tend to top people’s list of common nightmare fuels, but the handiwork of makeup artist David B. Miller (A Nightmare on Elm Street: The Dream Child) could change that. Miller was saddled with a challenge back then: “How do you make a burlap sack look scary?” The artist, as he told Fangoria in 1995, eventually settled on “an asymmetrical combination of a real sack and half a prosthetic facial structure to allow for movement.” It is certainly more complicated than Jason Voorhees’ first-ever headpiece, and it predates a kindred mask worn by Trick ‘r Treat icon Sam. So many times, the more the audience sees of these monsters, the more they become desensitized. In this case, though, the Scarecrow looks unnerving in almost every shot. And Howard Swain‘s sinister body movements along with those all too visible facial expressions beneath the sack are major reasons why.

Admittedly, the story here is as derivative as they come. John Carpenter already nailed the uncanny revenge tale with The Fog long before Night of the Scarecrow cropped up. However, the plot of a hedonistic warlock (John Lazar) returning from the grave after 100 years, now as a malevolent and magical straw man, is a bit more unprecedented. The concept and execution are just different enough to distinguish this movie from the more widely known and similarly titled Dark Night of the Scarecrow — an ’81 made-for-television horror movie also about macabre vengeance — and other stories of spectral retaliation.

“Sins of the father” is an unmistakable theme in this movie. The ostensible protagonist, Elizabeth Barondes’ refreshingly determined character Claire Goodman, returns to her hometown of Hanford after a long absence to question the construction of a new mall on the cornfield. That field was intended to help the whole community, but like in the past, those in power — exclusively Claire’s father (Gary Lockwood) and uncles — only care about their own interests. Film historian Amanda Reyes further dissects the Goodman oligarchy in her article Sex, Lies and Scarecrows: Reflecting on the Night of the Scarecrow. Reyes also says the Scarecrow himself is a “metaphorical rendering of a town, and of a family, constructed through a patchwork history.”

Image: Elizabeth Barondes’ character Claire meets John Mese’s character Dillon for the first time.

While the hoary setup makes it plain as day regarding who the warlock-turned-scarecrow will punish, he’s not opposed to incidental bloodshed as well. Claire’s more neutral relatives, who are still more than happy to look the other way and reap the benefits of their family’s unethical behavior, and a few other unlucky residents pad out the movie’s sizable body count. Burr understood he was making what he himself labeled a “set piece movie.” To compensate for a formulaic and repetitive story, though, he tried to make each of those set pieces equal or better than the last. And, for the most part, Burr achieved his goal. The Scarecrow’s dark journey is paved with only a handful of grisly scenes, but each one leaves a mark. From Claire’s father being consumed by a cocoon of living straw to the visceral “impregnation” of a clergyman’s daughter, this movie fits in well with other prevailing horrors that nearly cross a line. DTV movies in the ‘90s were recognized for their nondiscriminatory and unremorseful violence, and Night of the Scarecrow is no exception.

Burr was once quoted as saying, it was “almost impossible to create a truly breakthrough horror movie in a corporate structure.” He was specifically referring to this movie’s producers who sought a franchise before even finishing the first entry. Burr, who was aware of the irony of a sequel director complaining about franchises, simply wanted to make a good movie, then toy with the idea of a follow-up. Needless to say, talks of Night of the Scarecrow continuing didn’t amount to anything, despite the first movie leaving the story open for a sequel. Financial failure was the real reason a franchise didn’t happen, but keeping this as a one-and-done event was the right choice. And if there was ever a possibility of using all the Freddy Krueger-esque quips purged from the original script in a sequel, then ending things here was definitely for the best. The Scarecrow didn’t need a personality other than “seek and destroy.” It’s his largely straightforward demeanor that makes the movie’s horror bits so potent.

At the time, Jeff Burr feared Night of the Scarecrow would end up being only a “good formula movie.” As understandable as his concerns were, sometimes that is exactly what horror fans want. A well-made genre story with set pieces so vivid that they become etched in viewers’ minds even after years of not seeing the movie. It’s hard to come by this hidden gem now that Olive Films is defunct and their beautiful re-release is out of print, but here’s to hoping that’s not the last we see of one of the most frightening scarecrows to ever escape the cornfield.

Image: Gary Lockwood’s character’s body is taken over by straw.

Editorials

Silly, Self-Aware ‘Amityville Christmas Vacation’ Is a Welcome Change of Pace [The Amityville IP]

Twice a month Joe Lipsett will dissect a new Amityville Horror film to explore how the “franchise” has evolved in increasingly ludicrous directions. This is “The Amityville IP.”

After a number of bloated runtimes and technically inept entries, it’s something of a relief to watch Amityville Christmas Vacation (2022). The 55-minute film doesn’t even try to hit feature length, which is a wise decision for a film with a slight, but enjoyable premise.

The amusingly self-aware comedy is written and directed by Steve Rudzinski, who also stars as protagonist Wally Griswold. The premise is simple: a newspaper article celebrating the hero cop catches the attention of B’n’B owner Samantha (Marci Leigh), who lures Wally to Amityville under the false claim that he’s won a free Christmas stay.

Naturally it turns out that the house is haunted by a vengeful ghost named Jessica D’Angelo (Aleen Isley), but instead of murdering him like the other guests, Jessica winds up falling in love with him.

Several other recent Amityville films, including Amityville Cop and Amityville in Space, have leaned into comedy, albeit to varying degrees of success. Amityville Christmas Vacation is arguably the most successful because, despite its hit/miss joke ratio, at least the film acknowledges its inherent silliness and never takes itself seriously.

In this capacity, the film is more comedy than horror (the closest comparison is probably Amityville Vibrator, which blended hard-core erotica with references to other titles in the “series”). The jokes here are enjoyably varied: Wally glibly acknowledges his racism and excessive use of force in a way that reflects the real world culture shift around criticisms of police work; the last names of the lovers, as well the title of the film, are obvious homages to the National Lampoon’s holiday film; and the narrative embodies the usual festive tropes of Hallmark and Lifetime Christmas movies.

This self-awareness buys the film a certain amount of goodwill, which is vital considering Rudzinski’s clear budgetary limitations. Jessica’s ghost make-up is pretty basic, the action is practically non-existent, and the whole film essentially takes place in a single location. These elements are forgivable, though audiences whose funny bone isn’t tickled will find the basic narrative, low stakes, and amateur acting too glaring to overlook. It must be acknowledged that in spite of its brief runtime, there’s still an undeniable feeling of padding in certain dialogue exchanges and sequences.

Despite this, there’s plenty to like about Amityville Christmas Vacation.

Rudzinski is the clear stand-out here. Wally is a goof: he’s incredibly slow on the uptake and obsessed with his cat Whiskers. The early portions of the film lean on Wally’s inherent likeability and Rudzinski shares an easy charm with co-star Isley, although her performance is a bit more one-note (Jessica is mostly confused by the idiot who has wandered into her midst).

Falling somewhere in the middle are Ben Dietels as Rick (Ben Dietels), Wally’s pathetic co-worker who has invented a family to spend the holidays with, and Zelda (Autumn Ivy), the supernatural case worker that Jessica Zooms with for advice on how to negotiate her newfound situation.

The other actors are less successful, particularly Garrett Hunter as ghost hunter Creighton Spool (Scott Lewis), as well as Samantha, the home owner. Leigh, in particular, barely makes an impression and there’s absolutely no bite in her jealous threats in the last act.

Like most comedies, audience mileage will vary depending on their tolerance for low-brow jokes. If the idea of Wally chastising and giving himself a pep talk out loud in front of Jessica isn’t funny, Amityville Christmas Vacation likely isn’t for you. As it stands, the film’s success rate is approximately 50/50: for every amusing joke, there’s another one that misses the mark.

Despite this – or perhaps because of the film’s proximity to the recent glut of terrible entries – Amityville Christmas Vacation is a welcome breath of fresh air. It’s not a great film, but it is often amusing and silly. There’s something to be said for keeping things simple and executing them reasonably well.

That’s a lesson that other indie Amityville filmmakers could stand to learn.

The Amityville IP Awards go to…

- Recurring Gag: The film mines plenty of jokes from characters saying the quiet part (out) loud, including Samantha’s delivery of “They’re always the people I hate” when Wally asks how he won a contest he didn’t enter.

- Holiday Horror: There’s a brief reference that Jessica died in an “icicle accident,” which plays like a perfect blend between a horror film and a Hallmark film.

- Best Line: After Jessica jokes about Wally’s love of all things cats to Zelda, calling him the “cat’s meow,” the case worker’s deadpan delivery of “Yeah, that sounds like an inside joke” is delightful.

- Christmas Wish: In case you were wondering, yes, Santa Claus (Joshua Antoon) does show up for the film’s final joke, though it’s arguably not great.

- Chainsaw Award: This film won Fangoria’s ‘Best Amityville’ Chainsaw award in 2023, which makes sense given how unique it is compared to many other titles released in 2022. This also means that the film is probably the best entry we’ll discuss for some time, so…yay?

- ICYMI: This editorial series was recently included in a profile in the The New York Times, another sign that the Amityville “franchise” will never truly die.

Next time: we’re hitting the holidays in the wrong order with a look at November 2022’s Amityville Thanksgiving, which hails from the same creative team as Amityville Karen <gulp>

You must be logged in to post a comment.