Editorials

Rebirth: How Frankenstein’s Monster Stories Remain Relevant in 2024

“More original horror!” is always a curious statement to read from fellow horror fans. In the last few years, we’ve seen everything from a modern resurgence of new slashers, to subversive takes on the home invasion subgenre that once dominated the 2000s, to the slow, gradual return of fresh horror comedies. True, franchises may have a chokehold on the box office and wholly original concepts may be rare after a century of cinema, but contemporary horror always manages to reinvent itself by recycling classic storytelling frameworks and updating them with inventive twists, as horror is and will always be cyclical.

Mary Shelley’s original classic Frankenstein novel— a reflection on morality of new science and Galvanism of the time and the subsequent potential impacts on life and death— has spawned hundreds of movies, TV series, novels, stage adaptions, video games, and comics, and over two centuries later, creators are still finding new ways to modernize its central story. Or, rather, creators are still utilizing its central story as a skeleton to tell harrowing modern stories in digestible ways, particularly with three of the latest film adaptions in 2023 (plus one with a festive twist, the newly released Santastein.)

With few (if any?) male characters in the mix, Laura Moss’ Birth/Rebirth grapples with modern family structures, as two vastly different women from different walks of life find themselves as partnered mothers to a little girl who dies suddenly— the one being her actual mother and the other responsible for bringing her back to life. Despite their differences, both women represent different facets of single motherhood and modern womanhood in the 21st century, as the girl’s actual birth mother conceived her via IVF and working hours on end to support her, while the other is so clinical and unaffectionate in her approach to caring for the girl that the girl is seen as merely experiment fodder to the woman.

The latter woman seems to have little interest in birthing and raising children of her own, instead, using her reproductive system and its materials as a means to aid the reanimation of her experiments, to the point of eventual cervical damage. After her cervix gives out, both women come together to find pregnant women (and use their pregnant bodies’ plasma) to keep the little girl alive. One woman does it for love; the other does it for science. While not explicitly romantically involved, the newfound relationship between the two women with a common goal could even be perhaps considered queer-coded, depending on the viewer, which feels very Bride of Frankenstein.

‘birth/rebirth’

Birth/Rebirth is one of the only reanimation flicks to hyper-focus on the specificity of female bodies and all their complicated nuances, which it never shies away from showing to the audience, to the point of comparisons to all things Cronenberg. And as the mad scientist performs the pregnancy abortions on herself for her experiments, she always remains in control of her bodily autonomy. Nobody is objectifying or making a spectacle of her body in a sexual way, and Moss’ choice to force the viewer to really look at all the graphicness (the post-pregnancy blood) standardizes its normalcy of these procedures in everyday real women’s lives, which is seldom seen in these films. True to a Frankenstein tale, the lines of morality are blurred and complicated, as both women resort to anything to keep this reanimated girl alive, even after she exhibits signs of violence and aggression. Moss nor her script itself judges the grisly acts of these women— they leave that up to the viewer.

Released just a few years after the Black Lives Matter movement especially came into prominence, Bomani J. Story’s timely The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster puts a Black teenage girl in the driver seat of the mad scientist story— a rarity in the Frankenstein subgenre. After losing her mother and brother to gun violence, the “angry” Black girl believes death is a disease that can be cured, pissing off her racist teachers who resent her defiant worldviews. She lives with her father in the projects, where she secretly starts experimenting with Galvanism to bring her late brother back to life, but, naturally, her brother doesn’t come back the same, as they never do. Like Victor Frankenstein, Vicara (Laya DeLeon Hayes) has suffered so much loss in her life that believing death can be fixed is an understandable coping mechanism— factor in watching her community get torn apart by socioeconomic injustices like violence, drugs, and police corruption, and her so-called anger and desire to enact change feels more than justified.

Even through its contemporary lens, Angry Black Girl readdresses the core theme of the original Frankenstein story that perhaps we’re doomed to become what people say we are. After she reanimates him, Vicara’s brother stalks the neighborhood at night and gets accused of being a monster, until he eventually indeed behaves like one, and the death toll continue to rise in the neighborhood. Spiraling out of her control, Vicara’s monster ravishes his way through whatever is left of (their) family, until Vicara’s talents can bring some members back. Her family is reborn again.

‘The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster’

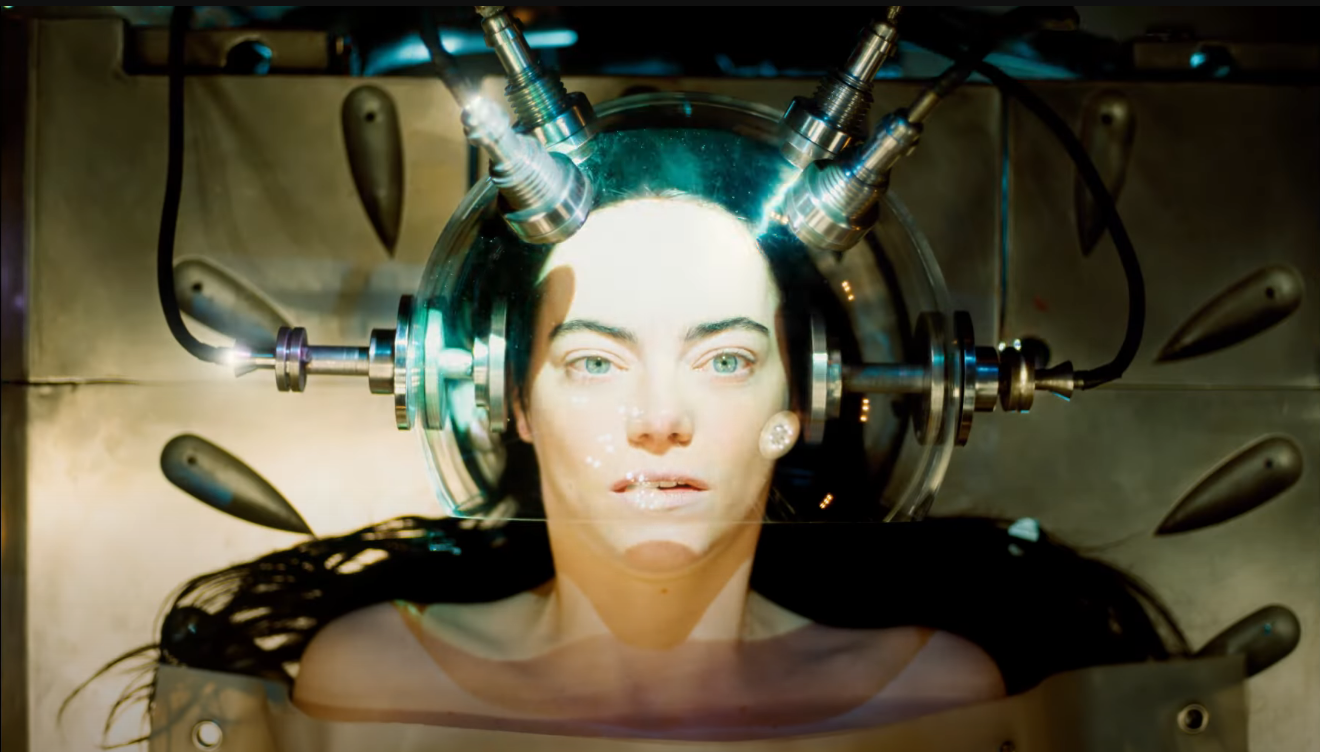

Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things begins in black and white in the Steampunk era, as the newly resurrected Bella (Emma Stone) awkwardly stumbles around mad scientist Godwin’s (Willem Dafoe) mansion, likely as both a visual aid for, what begins as, the metaphorical lack of color in Bella’s life and as a nod to the original Universal Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein films. Godwin, or God, had discovered Bella’s pregnant corpse after taking her own life and presumes that, since Bella herself had no desire to live, he should give her unborn baby a chance and reanimates Bella with her unborn baby’s brain. The reborn Bella learns at rapid pace and refuses to give into conventional social politeness, indulging in all things sex, desserts, and anything else that give her pleasure— even turning to sex work simply because she enjoys getting paid to have sex.

Adapted from Alasdair Gray’s 31-year-old novel of the same name, Poor Things trades scares for laughs, save for some eye-stabbing a corpse and Bella’s darkly, darkly funny fascination with the macabre. In fact, the scariest thing in the film (to the male characters surrounding her) is her unabashed sexual appetite, or her need to get “c*cked,” as she calls it, and her refusal to comply to anything they want her to do. Lanthimos recently recalled how long the film took to get made, and perhaps the long wait was a blessing in disguise, as these unapologetically raunchy desires of a female character are much more digestible for 2023 audiences than they would’ve been a few decades prior, post-Sex and the City, post-“SlutWalk,” and within the dawn of the OnlyFans era. Whereas the novel tells Bella’s story through other characters’ perspectives, Lanthimos’ film is told through hers.

But Bella’s sexuality isn’t her only desire in her journey to self-discovery: she wants to become a doctor like her father figure Godwin, just like he wanted to become a doctor after his own father. Godwin’s grotesque facial features are the result of serving as his father’s scientific experimental muse, which Godwin perceives as an honor (though the modern audience watching knows this was really abuse.) His background makes sense as to why he’s protective but proud of Bella, in spite of all her rebellion. In lesser Frankenstein adaptations, the Godwin character would fail to be nuanced and be played as more monstrous, emphasizing the “mad” in mad scientist; instead, Godwin is appalled when another character suggests that he created Bella as his own sexual toy (the joke being that, of course not, but also because he is a eunuch.)

‘Poor Things’

While the glut of Frankenstein films— stemming from Shelley’s original Victor Frankenstein himself— feature men in the “mad scientists” roles, Birth/Rebirth, Angry Black Girl, and Poor Things subvert this trope, as even the experimented-on woman Bella is becoming a doctor herself. All of these women are seeking knowledge and are smarter than their male counterparts (in the films in which men do exist, at least.) The women are looking for a sense of control over their lives, and ultimately get it, to varying degrees of success— which simultaneously feels both updated and faithful to the roots of Mary Shelley’s complicated feminist legacy.

The release timing of these films is coincidental, but the “reborn” motif they share feels particularly resonant in 2023. The entertainment industry itself is undergoing a rebirth, as it navigates post-pandemic streaming-versus-theater release consumption and its recovery after the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. The massive success of Barbie has now pushed the demand even further for female-driven stories like these ones into the mainstream market. Even one of the highest grossing concert tours of 2023 was Beyoncé’s “Renaissance” tour, which, by definition, means rebirth or revival. As per usual, horror has proven itself a foreseer of all of it, with thematically relevant films like these and its own rebirth, as horror has had a huge hand with keeping box offices alive and well in these turbulent times with no signs of stopping.

Editor’s Note: Up next? Lisa Frankenstein comes to theaters on February 9, 2024!

Editorials

Faith and Folly: The Religious Dialogue Between ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The Wicker Man’

In December of 1973, two movies that would change the face of horror and the ways it dealt with religion and spirituality were released. One was an instant hit, immediately changing the landscape of the genre forever. The other was severely cut by executives who simply did not understand it and unceremoniously slapped into the B-picture slot on double bills with Don’t Look Now, where it seemed to die a quick death. Over time, it grew from an underground cult discovery to a genre-defining masterpiece. The former is, of course, William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, which remains a terrifying and inimitable masterpiece. The latter is Robin Hardy and Anthony Schaffer’s The Wicker Man, a truly remarkable film that became a flashpoint for an emerging subgenre—Folk Horror. Though both films deal in religion, The Exorcist and The Wicker Man could not be more divided in their approach to the subject. Because of this, the two make excellent debate opponents, sparring with one another about the eternal questions that mankind has wrestled with since the beginning of thought.

Despite their differences, the two films have several commonalities as well. Both eschew the traditional tropes and aesthetics of the classic horror movie in favor of a grounded, realistic style. This is typical now but revolutionary, especially for studio-produced horror films, fifty years ago. William Friedkin approached The Exorcist with the same detail-oriented documentarian’s eye that he applied to The French Connection (1971), and would later bring to Sorcerer (1977), Cruising (1980), To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) and other films throughout his career. The Wicker Man takes the visual approach of a travelogue, taking in both the natural beauty and anthropological quirks of Summerisle with curiosity, wonder, and more than a little suspicion.

Some cuts of the film begin with a title card thanking Lord Summerisle (played by Christopher Lee) for his cooperation in the making of the film for added realism. In fact, both films claim connection to real events. Writer William Peter Blatty was inspired to write his novel The Exorcist after learning of a case of supposed demon possession of a young boy while studying at Georgetown University in 1949. Though ostensibly based on the novel Ritual by David Pinner (both Christopher Lee and Robin Hardy have said that almost nothing of the novel made it to screen), The Wicker Man sprang largely from exhaustive research by writer Anthony Shaffer and director Robin Hardy of The Golden Bough, an extensive study of pagan beliefs, rituals, and traditions by James George Frazer.

‘The Wicker Man’

It may seem insignificant, but another notable similarity between the two films is that the name of the writer, rather than the director, appears above the title of both, truly a rarity in the New Hollywood era that had bought wholesale into the auteur theory. But the writing of both films (and frankly most films) is foundational to their success. The key to the lasting effectiveness of The Exorcist is its complete conviction in the way it is told, which all stems from the writing. William Peter Blatty was a true believer—in God, the Devil, and the power of exorcism. He felt that the case that inspired his novel “was tangible evidence of transcendence,” and attempted to convey what he saw as the reality of the supernatural in what he wrote. Though not a person of traditional religious faith himself, William Friedkin was determined to translate this conviction to the screen. In an introduction to the digitally remastered home video release, he summarized this by saying “…it strongly and realistically tries to make the case for spiritual forces in the universe, both good and evil,” believing that it could very well alter perceptions in the process.

The Exorcist’s point of view is clear—God is good, the Devil is bad, and good will ultimately triumph over evil, even if evil wins some victories along the way. The Wicker Man is more cynical and Anthony Shaffer’s views of good and evil, heroes and villains are far more ambiguous. On the surface, Lord Summerisle, aided by the fact that he is played by Christopher Lee, is the villain. After all, he does entrap and condemn an essentially innocent man to death to appease one of his bloodthirsty gods and perhaps save his own skin. Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward), on the other hand, is no hero either. He is an outsider to Summerisle and from beginning to end judges and condemns their community practices and religious beliefs. He is the embodiment of colonialism invading an unfamiliar land, attempting to bend it to his will and belief systems. When it comes down to it, neither is completely a hero or a villain. The real villain of The Wicker Man is religion itself. In the end, neither Sergeant Howie’s conservative brand of Christianity nor Lord Summerisle’s neo-paganism come out looking good at all. In fact, it seems that writer Anthony Schaffer’s point is that neither Howie’s Christian God nor Summerisle’s nature spirits will answer in the end because, in the film’s point of view, neither exists. The Wicker Man’s conviction is just as strong on this viewpoint as The Exorcist is on its opposing one.

In this respect, more than any other, the two films most clearly define the biggest difference between the cousin subgenres of religious and folk horror, though these differences have begun to blur in more recent films. Religious horror generally deals in good and evil, and religious institutions often come out looking heroic, as in The Omen (1976), The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005), and The Conjuring (2013) despite the results of the acts practitioners of the faith in these films may be involved in. In folk horror, organized religion is folly and often brings oppression, as seen in films like Witchfinder General (1968), Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Witch (2015). These distinctions are perhaps most clear in The Exorcist and The Wicker Man, a key reason why they are often considered the pinnacles of their respective subgenres.

‘The Exorcist’

The key forces for good in The Exorcist stand at different places along the spectrum of faith but all make the case for the positive effects of religion, even the agnostic Chris MacNeil so expertly and passionately played by Ellen Burstyn. Though she is not a believer herself, she does everything she can to save her daughter Regan (Linda Blair) from the evil that has taken her including bringing her to people of faith. After she has exhausted every avenue she knows, she turns to the priests that inhabit the city where she and Regan temporarily live, sometimes with more faith in their practices then they have themselves. Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) spends most of the film doubting his faith and tries to talk Chris out of pursuing exorcism for her daughter. The apparent hero of the film, Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow)—he is even given several heroic shots including the iconic approach to the house in the fog—is a man of unshakable faith having endured an exorcism before, but also one of frail health who dies while attempting to take on the demon by himself. It is a powerful statement of The Exorcist that the doubter, Father Karras, becomes the heroic figure of the film, sacrificing himself for a relative stranger.

Underrated in the dynamic is Father Dyer, played by real-life priest William O’Malley, who like Karras is very human, but also the one who performs the last rights on Karras. Therefore, it is Father Dyer who finally exorcises the demon (named as Pazuzu in the novel) from the last human it inhabited and perhaps most fulfills the titular role of the exorcist. The powerful original ending to the film with Dyer staring down the stairs that his best friends threw himself down reinforces that good continues to shine a light in a very dark world. Feeling that people would think “the Devil won,” Blatty never liked the theatrical ending, and so the closing scene in which Dyer carries on Karras’s friendship with Lieutenant Kinderman (Lee J. Cobb) in his friend’s absence was added to the film in 2000. In the opinion of many, this reinstated ending sullies the power of the film, which thrives on the ambiguity raised by sequences like the original ending.

The Wicker Man has no problems with ambiguity in any of its extant versions and invites each viewer to thoroughly question every element of the film. Both Howie and the islanders see the religious practices of the other as a collection of superstitions. The novelization of Anthony Shaffer’s script by Robin Hardy offers even more shades of grey to Neil Howie and Lord Summerisle, as well as the beliefs they each profess. Howie is far more fascinated by the islanders and their practices, at least at first, than judgmental of them in the novel. He even secretly wishes that he could join them in the sexual escapades he witnesses on his first night on the island. His desire to give into Willow MacGreagor’s (Britt Ekland) seductive song on May Day Eve is palpable in the film but even more so in the novel. This is Howie’s greatest test, his Garden of Gethsemane. By resisting the beautiful, and very willing Willow, he becomes even more the fool in the eyes of the islanders, but for Howie, it proves his fidelity to his fiancée, his morality, and his God.

‘The Wicker Man’

The novel reveals that Howie and Lord Summerisle’s differences are not only religious, but political. As a socialist, Howie is deeply offended by the aristocratic Summerisle and the capitalist machinations of his island community, but the officer greatly admires him as a professional. The novel also is more nuanced in depicting how people of various faiths often misunderstand each other. For example, the islanders interpret the Christian practice of Communion as symbolic cannibalism, where Howie sees it as an act of remembrance of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. The novel draws several more comparisons between the islander’s faith and Christianity than the film does, specifically in a subplot involving the character Beech (which if it was shot was cut from all versions of the film), and discussions of death, resurrection, and sacrifice.

Beech, who adheres to his duty of guarding the “sacred grove” with a claymore sword, is seen as a crazy old man by most of the islanders, including Lord Summerisle himself. The comparison here is that Beech’s form of worshipping the old gods is different from most of the inhabitants of the island, highlighting the different sects and denominations of various religions including Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and many others. Though not organized in the same way as these, the religion of Summerisle has factioned in similar ways. As for death and resurrection, the schoolteacher, Miss Rose (Diane Cilento), both in the film and the novel, tells Howie as he is being guided to his fate, “you will undergo death and rebirth. Resurrection if you like. The rebirth, sadly, will not be yours, but that of our crops.” Howie responds with, “I am a Christian and as a Christian I hope for resurrection, and even if you kill me now it is I who will live again, not your damned apples!” Earlier in the film, she tells Howie that reincarnation is much easier for children to grasp than all those rotting bodies being resurrected. In the novel, Howie secretly agrees with this assessment.

But the ultimate focus of both films is the nature of sacrifice and the significance it may or may not have on the lives of others. In The Exorcist, both Father Merrin and Father Karras make the ultimate sacrifice by giving their lives to save Regan, as Chris no doubt would do herself if it came to it. In the Christian view, sacrifice is a willing act. In the more everyday sense, the giving of time, talents, and treasure to serve other people. In the ultimate sense, the laying down of one’s life for another person as exemplified by Jesus Christ himself who gave up his life to save the world from sin. This is the view of sacrifice shared by Sergeant Howie, who seems very puzzled by the words of May Morrison (Irene Sunters), the woman whose missing daughter he is searching for, when she says, “you will never know the true meaning of sacrifice.”

‘The Exorcist’

Here, however, Howie’s sacrifice is unwilling, a coercion that leads to his ultimate demise. Shaffer and Hardy keep the final verdict up to interpretation and speculation, allowing each viewer the opportunity to extrapolate their own conclusions about what awaits Howie and Summerisle after the Wicker Man and its contents crumble to ash. The novel retains the cynical tone of the film with its final line: “And as for Howie, it would be good to think that all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.” Perhaps this is the case, and he is afforded the rewards of the martyr’s death that Summerisle has “gifted” him. Perhaps a bounteous harvest awaits the inhabitants of the island. Or perhaps it is all for naught and all that awaits Howie is eternal silence, the crops fail once again, and Lord Summerisle is doomed to endure the Wicker Man the following May Day.

The dialogue between The Exorcist and The Wicker Man will no doubt continue. In recent years similar discussion points along with deconstructions and variations on the debate can be found in Saint Maud and Midsommar (2019), Midnight Mass (2021), Consecration and The Pope’s Exorcist (2023), and from this year Immaculate, Late Night with the Devil, and The First Omen along with other films that represent the largest wave in religious-themed horror since these two seminal masterpieces were released over fifty years ago. In the debate we find a deep longing for answers to the ultimate questions about ourselves and our place in the universe. Is there good and evil beyond what is found in the hearts of humans? If so, is there a singular god, or gods, or some kind of forces for good and evil? And maybe what we want to know most of all, if there is a god or gods, do they give a shit about us?

The Exorcist seems to answer all these questions in the affirmative. In that, many find hope. The answer to good and evil is not up to us but will be finally and fully solved by a power greater than ourselves. We can find comfort in that. The Wicker Man seems to say “no” to these questions, but there is a kind of hope in that as well. If nothing outside of us determines good or evil, it is up to us to solve the problem of evil, to eradicate it from ourselves and replace it with good. We can find comfort in that too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.